Music as Activism

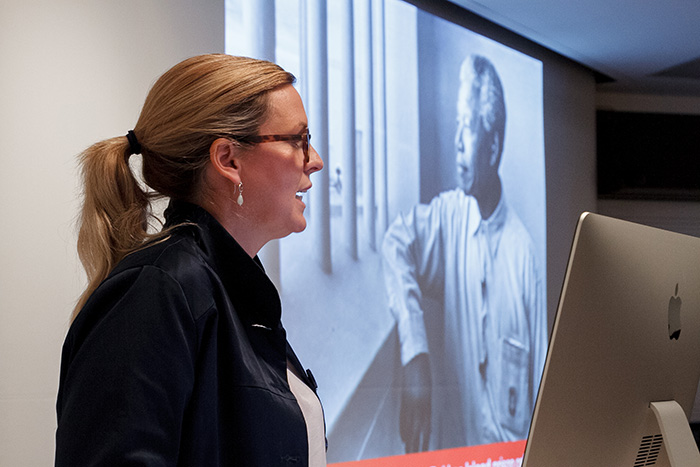

Musicologist, oral historian and documentarian Janie Cole speaks with students in a First-Year Seminar about music of the anti-apartheid movement. Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

Residency explores music of the anti-apartheid movement

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

The conditions at the Robben Island prison could easily break a spirit: six-foot-square, solitary rooms; a meager diet, combined with hard labor; bullying, beating and humiliation; inadequate clothing; and next to no contact with the outside world. How did Nelson Mandela and fellow anti-apartheid activists survive long-term sentences?

In part, through song, says award-winning musicologist and oral historian Janie Cole, who studies the ways that apartheid-era political prisoners used vocal music to transcend their surroundings, build community and resist oppression. This week, she served a residency at Dickinson to share her ongoing work.

The founder and executive director of Music Beyond Borders, Cole holds a Ph.D. from the University of London and teaches historical musicology at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for African Studies and the South African College of Music. She’s building a digital oral-history archive of interviews with, and songs sung by, former prisoners of Robben Island, as well as interviews with former staff members. Her documentary on the subject, Keeping Time, is currently in production.

During her three-day stay, Cole presented her research and screened clips of her documentary to students in history, Africana studies, sociology and music classes. She also presented a public lecture and screening and attended a dinner with students in an oral-history mosaic, sharing tips from the field.

Victoria Lynott ’19, a pianist, attended the lecture as well as a presentation on music-making and bravery that Cole delivered to her First-Year Seminar. She was fascinated by the parallels between the ways that folk songs can help communicate and frame lived experiences and the ways that movie soundtracks can help shape onscreen narratives.

Meg Booth ’19 approached the topic from an activist's perspective, having become involved with social-justice organizations in high school. "Through her research, Dr. Cole has captured the voices of people whose stories would [otherwise have been] lost, yet are an essential part to the apartheid narrative," she noted. "It helps us understand apartheid beyond the information usually presented."

"Like most people, I knew that music was a platform for self expression, but I never thought of it as a powerful tool to [spark] changes in a society, to the extent of being the catalyst to ending apartheid in South Africa," added Titilope Ogunsola ’19. "As a result [of this residency], every time I listen to or sing a song I now pay particular attention to its meaning and motive."

Learn more

- November Calendar of Arts

- Visiting Artists and Artists-in-Residence

- The Arts at Dickinson

- Department of Music

- Latest News

Published November 12, 2015