Going Local

Amy Witter, associate professor of chemistry, conducts research for her article, "Coal-tar-based sealcoated pavement: A major PAH source to urban stream sediments." Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

by Michelle Simmons

Whether it’s mining the past, polling the campus community or testing the waters (literally), place-based student-faculty research and experiential learning is thriving at Dickinson.

If you were to take Assistant Professor of English Siobhan Phillips’ course Writing About Food, you might write about volunteering at the local food bank, Project SHARE, founded by Elaine Livas ’83. Or consider the multitude of projects conducted every summer at or for the College Farm, such as building a crop-rotation algorithm. There’s so much happening at the farm now that there’s a student-faculty team creating a database of all those research projects.

For indomitable faculty members Maria Bruno, Andy Skelton and Amy Witter and their students in the following three stories, that research can get a bit messy and unpredictable, whether it’s delayed by an unusually fierce winter followed by a long mud season or the work launches a rhetoric war because the study results might have a negative impact on a particular industry.

What ties these disparate disciplines and personalities together, though, is their focus on going local in deep and thoughtful ways, with long-term consequences, such as leading the campus community toward carbon neutrality. Or changing the way we coat our driveways. Or even rethinking how we think about research.

Over the Hill and Through the Woods

About 16 miles west of Dickinson and along the Appalachian Trail lies a 250-acre wooded area dotted with collapsed foundations, partially hidden under decades of forest growth. A few steps from a smallish parking lot squats a pock-marked, six-foot-round concrete marker, with the letters POW just barely visible on its face. Several more steps, and you’ll come upon a fountain fashioned with cement and glittering blue bits of iron slag, full of leaves and detritus.

From farm to camp to penitentiary and back to camp again, the site — now known as Camp Michaux — has become a boon to Maria Bruno, assistant professor of archaeology and anthropology. With support from the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission (PHMC), Bruno is helping students in her Archaeological Method and Theory class gain hands-on experience in surveying, mapping and, ultimately, excavation. They, in turn, are providing the PHMC and the Cumberland County Historical Society (CCHS) systematic data about the archaeological record of this important place.

Established in 1785 as the Bunker Hill Farm, it and other nearby farms later supported the laborers working at the Pine Grove Iron Furnace and surrounding quarries into the late-19th century. After the collapse of the iron industry, the land lay fallow until 1933, when 200 men arrived to construct one of the thousands of Civilian Conservation Corps camps to pepper the country during the Great Depression.

They laid roads, installed telephone lines, reforested land and built infrastructure for a nascent state park. With the start of World War II, however, the 40-plus buildings were shuttered until 1943, when the War Department realized the location’s value as a secret interrogation site for German and, later, Japanese prisoners of war.

The camp saw further use in the 1960s as a church summer camp, until the main lodge burned down in 1972, and the land became part of Michaux State Forest.

“David Smith and the Camp Michaux Recognition and Development Project have been compiling the rich historical information on the site and have also developed a nice walking tour of the area,” says Bruno. “But there is much to be learned from an archaeological perspective, which relies on the materials left by the people who lived there. Many aspects of daily life go unrecorded in historical records, and historical maps or accounts can sometimes be inaccurate.”

Bruno got her sense of the Cumberland Valley’s archaeological richness when she participated in Valley & Ridge, a program launched by Dickinson’s Center for Sustainability Education to help faculty -members inject place-based and experiential education into their curriculum. Since 2008, more than 50 faculty members have participated in the summer program, which has resulted in new or revised courses in disciplines as wide-ranging as political science, sociology, biology, international business & management and English.

Although Bruno’s primary research before coming to Dickinson was on the origins of agriculture, including the domestication of quinoa in Bolivia, the opportunity to work locally was too good to pass up, and it fit her already ingrained sustainability ethos.

Her class, which she introduced in 2013, incorporates bibliographic research as well as guest lectures that cover cultural history, climate and the environment, archaeological aerial survey methods and sampling strategies. Students then conduct fieldwork during the second half of the semester, culminating in oral presentations on their research and written research proposals for further work there.

“Because the archaeology faculty has research areas in Greece and South America, this course provides one of the few opportunities for students to learn about archaeology of the region in which they currently reside,” Bruno notes. “This place-based approach also generates important opportunities for students to engage with the community.”

In addition to working with Smith at the CCHS, Bruno also is tapping expertise from within the Dickinson community, including GIS Specialist Jim Ciarrocca, who is helping with the on-site survey and mapping, and biology instructor Gene Wingert, who as guest lecturer provided a natural history of the area.

Anthropology and archaeology double-major Justin Reamer ’15, who took Bruno’s course in spring 2013, is now conducting an independent study for a senior honors thesis, with the hope of finding evidence of prehistoric American Indian presence at Camp Michaux. Because of significant meta-rhyolite deposits in the region — meta-rhyolite being an important source of early stone tools — Reamer believes that there may be artifacts to prove his thesis.

“Little to nothing is known about the area in the prehistoric period,” he says. “The potential of finding something there really excites me — to find quarries and to figure out what the area was used for. Professor Bruno has really high hopes that we’ll find something.”

After a long and difficult winter, in April, Bruno’s class, along with archaeology major Karl Smith ’14, who was working on his own independent study taking old Michaux maps and digitizing them into GIS maps, began their second round of surveying and mapping, using both GIS and an older, more simplified technology — a compass, tape measure and clipboard.

In one spot, two students measured and sketched out the diameters of an old pump house at the edge of a creek; elsewhere, a group of three walked slowly, their gaze glued to the forest floor. Others took turns learning how to “look beyond, not through” the Total Station viewfinder, as Ciarrocca put it.

“We’re just figuring out the scale of it all,” says Bruno. “That takes a lot of time.”

Good Intentions, Better Results

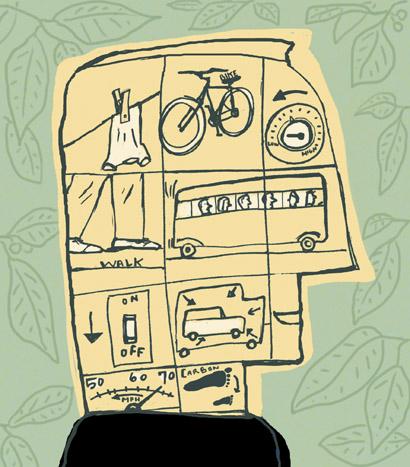

Illustration by Jud Guitteau.

So, you believe in living sustainably: You separate and recycle; you keep your thermostat at 65 in the winter and 72 in the summer; you drive a hybrid vehicle; you shop at a farmers market and buy only local or organic. You compost.

But here’s the rub: Sometimes you don’t feel like washing out that plastic container filled with unrecognizable goop that you found in the back of your fridge. Or you learn that the manufacture of your new hybrid might create a larger carbon footprint than keeping that 10-year-old diesel Volkswagen, but you buy it anyway. You’ve even talked with colleagues about carpooling to the office but, somehow, it never quite works out.

It turns out you’re far from alone, according to research on environmentally significant behavior (ESB) — individual behavior that can have impact on the environment, whether it’s limiting consumption of fossil fuels, minimizing waste or other sustainability-focused actions — being conducted by Associate Professor of Psychology Andy Skelton and several of his students.

“One of the things we talk about a lot in my classes is the difference between what people think they’re accomplishing,” he says, “and what they actually are accomplishing in terms of environmentally relevant behavior.”

Skelton had participated in faculty discussions as early as 2007 on how to integrate sustainability into Dickinson’s curriculum. “What it led to was the dedication of my upper-level courses to sustainability issues and how I could use psychology as a way of hooking students’ interest in sustainability,” he says. “A lot of issues having to do with consumption, waste and so forth have to do with our habits, who we associate with and how our expectations are set by the people we associate with.”

Since 2007, the college also has committed to a Climate Change Action Plan, which pledges carbon neutrality by 2020. One of the key challenges to meeting that goal is in transportation, and Skelton saw an opportunity to conduct solid research that could support the college’s sustainability initiatives.

The project began in fall 2012, in his Research Methods in Social Psychology class, when, as a class exercise, he and students created a survey on employees’ commuting practices. “These projects work very nicely in the sense that they give my students an opportunity to learn how you go about conducting surveys,” says Skelton. “What are the pros and cons of different approaches? How do you conduct a survey that asks the questions that you want and does it very efficiently?”

Students worked with staff in the Center for Sustainability Education and the Office of Institutional Research (IR) to design the survey, which used two methods to capture a wide sample: oral interviews via phone calls and an e-mail that linked to a self-administrated online survey.

“I learned about the unexpectedly complex obstacles that stand in the way of reaching respondents,” says James Cousins ’14, a mathematics major who worked with Skelton in an independent study. After graduating early, Cousins worked for IR and is now an analyst at Rapid Insight, a data-analytics and consulting company. “Surveying seemed far more straightforward on the surface than it turned out to be in practice.”

Thanks to students’ perseverance, the response was excellent, however, and they learned that an overwhelming majority of Dickinson employees drive to work. “We’re talking in the neighborhood of 85 percent,” he says. “It really has to do with the distance that you live from campus.”

Next came a wild idea, as he puts it. Given the dearth of public-transportation options in the area, he reached out to GIS Specialist Jim Ciarrocca: “One of the side effects of this [study] is that we’re now leveraging our GIS technology to learn more about the distribution of employees,” Skelton says. “Could we figure out where employees are concentrated, so that we could identify good matches for carpooling, ride-sharing, that sort of thing?”

The idea has piqued interest among members of the campus community, but Skelton is quick to point out that this is no Big Brother project, in which employees will be assigned carpool companions or be required to reveal their home address, and he notes that the survey results reflect cultural norms. “Everyone is well intentioned about the environment,” he says, “and everyone has a ton of habits that lead them to jump in their private vehicles whenever they need to. There’s always the balance between creating incentives for people not to drive and creating barriers to driving.”

And while he has tons of data, the discussion is just beginning. Since the initial survey in 2012, he and successive classes have improved on the model, crafting more sophisticated questions. For example, instead of asking whether one has driven to campus in the past week, they now ask how many days out of the week the person drives to campus. The difference is important, as they’ve since discovered that many do walk or bike to campus and drive only in bad weather.

“From the standpoint of a teaching tool, this has been really fertile for me,” he says. “The students seem to be more interested in this than in some abstract question of psychological theory, but you can always get that in there too.”

Toxic Science In a February issue of The New Yorker, a beleaguered biology professor and researcher at the University of California-Berkeley explains his world view: “The secret to a happy, successful life of paranoia is to keep track of your persecutors.” Tyrone Hayes, the subject of Rachel Aviv’s article, had been fighting a decade-long battle with Syngenta, a global bioengineering company that specializes in seeds and pesticides. Hayes had been contracted to study one of the company’s herbicides, atrazine; when he discovered that it interfered with the sexual development of amphibians — and possibly humans — the company severed its ties with him. He continued his research, and the article describes Syngenta’s subsequent campaign to discredit not only Hayes’ research but also his credibility as a scientist.

Whether or not Hayes’ paranoia is legitimate (“Even paranoids have enemies,” quipped Golda Meir), Aviv noted a growing trend among some industries to go after the scientists whose research may affect regulatory policy — from tobacco companies undermining research on secondhand smoke in the 1990s to the 2009 Climategate controversy over the hacked e-mails of the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia.

Enter Amy Witter, associate professor of chemistry at Dickinson. After her article “Coal-tar-based sealcoated pavement: A major PAH source to urban stream sediments,” appeared in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution, the Pavement Coatings Technology Council (PCTC), an organization of manufacturers of pavement sealants and their suppliers, issued a press release casting doubt on Witter’s methodology. Environmental Pollution also received a letter to the editor from the consulting firm Exponent Inc. questioning Witter’s analysis and accusing her of using misleading language. The firm had represented the Pavement Council in its opposition to Washington state’s 2011 bill banning use of the sealant.

Her article, co-written with Associate Professor of Earth Sciences Peter Sak, Minh Nguyen ’11 and Sunil Baidar ’09, presented evidence that local waterways were contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a probable human carcinogen and component of coal-tar-based pavement sealant often used on driveways and parking lots.

National retailers Lowe’s and Home Depot no longer carry the product, and other research into PAHs and its connection to coal-tar-based sealcoat has resulted in bans in Minnesota, several municipalities in the West and in Washington, D.C. The coal-tar-based product, which is less expensive than asphalt-based sealant, remains popular for commercial use east of the Continental Divide.

The PCTC letter arrived “pretty much the day after the article was published online,” says Witter. “Basically, every study that comes out, the PCTC refutes it.”

Witter began looking into PAHs in 2005. She had done some sediment analyses from the nearby Conodoguinet Creek and found PAH concentrations that couldn’t be accounted for—until she came across a paper published by the U.S. Geological Survey that identified coal-tar-based sealcoat as a possible source.

Because of heavy professional obligations, Witter wasn’t able to dive more deeply into the research until 2007, when she took more sediment samples, using a slightly different procedure for analysis. “Those samples were consistent with what we had seen in 2005,” she recalls. “And I really wanted to nail this thing.”

Witter brought in Sak and GIS specialists Kristin Brubaker and Jim Ciarrocca to help her examine land-use practices in areas where the samples were collected. Together with her students, she sampled a total of 35 sites and identified the sealant’s chemical signature.

“The source of stream PAHs can be determined much like DNA fingerprints can identify individuals,” she explains. “In our study, the PAH fingerprint of coal-tar-based sealcoat and the PAH fingerprint found in urban creek sediments were nearly an exact match, giving us a high degree of confidence that coal-tar-based sealcoat is an important PAH source in the Conodoguinet Creek watershed.”

In collaboration with colleagues at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, she planned additional work to quantify how significant the contributions from sealcoat may be throughout the watershed.

Witter also used additional, more stringent standards. Through a small sabbatical grant from Dickinson, she purchased the chemicals she needed and shipped her samples to the University of Toronto, where she worked with colleagues who provided access to equipment not available at Dickinson. “Since 9/11, sending scientific samples across the U.S. border and back again has become more complicated,” she says. “However, I did one part of the analysis there because I thought, if this is going to be published, it’s got to be done this way, and it’s got to meet all the criteria. Many of our colleagues at Dickinson go to extreme lengths to carry out their research, especially when students or fieldwork are involved. This was minor by comparison.”

Over several years, Witter continued to collect and study samples, and her article is based on samples taken in 2010. “This paper has been peer-reviewed probably six times,” she says. “I’ve never had to revise a paper as much as I’ve revised this one. It’s very contentious science.”

Since the publication of her article, Witter has responded twice to the PCTC’s counterclaims in Environmental Pollution. She stands by her study, but she worries about future research, citing similar attacks on the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the U.S. Geological Survey.

“That’s what this lobby relies on, that they’re going to bully you and grind you down so that you’ll change your research,” she says. “They just rely on casting doubt.”

Read more from the summer 2014 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Published July 22, 2014