Artists-in-residence Present Lost Music of World War II

Remote residency brings ‘Yiddish Glory’ to Dickinson

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

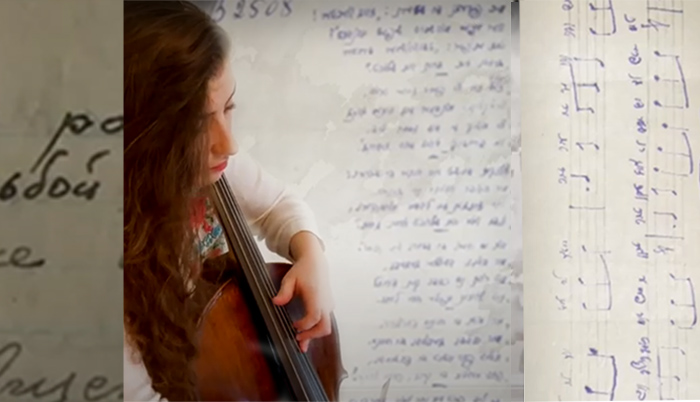

Twenty-six years ago, librarians at the Ukrainian National Library in Kiev discovered a treasure trove of notes and written stories, jokes and songs left behind by Soviet Jews during World War II. Filed away in dozens of unmarked boxes in a dank corner of in the building’s basement, these artifacts documenting Jewish experiences in Nazi-occupied Europe had been carefully preserved by a musicologist who’d later been imprisoned. Excitingly, none of the songs in the collection were familiar to Holocaust scholars or musicologists.

To give voice to the Soviet Jews who’d been silenced by the Hitler and Stalin regimes, Psoy Korolenko (aka Pavel Lion), a musician-poet and singer-songwriter, and Anna Shternshis, a leading scholar in Jewish history, teamed up to analyze and recreate those left-behind songs and bring them into the 21st century.

Last week, they shared their Grammy-nominated program, Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II, with the Dickinson community and met with students virtually to discuss their work. Their joint residency, co-sponsored by Dickinson’s Music Residency Program and the Truman & Beth Bullard Music & Culture Series, was one of several remote residencies the college is hosting this spring.

Korolenko and Shternshis Zoomed into a music history class taught by Professor of Music Amy Wlodarski and a Russian workshop and class taught by Associate Professors of Russian Alyssa DeBlasio and Elena Duzs, respectively. Their Yiddish Glory residency also included a March 26 livestreamed concert-lecture combining live and prerecorded performances, viewable for a limited time through the Department of Music YouTube channel. This included the world premiere of one song.

Throughout their interactions with Dickinson students and faculty, Korolenko and Shternshis shone a light on their three-year musical-archaeology project, recreating songs that have likely not been heard since the 1940s and documenting the eyewitness accounts of the war these song lyrics and notes contained. In some cases, the songs were notated. In other cases, only lyrics—or fragments of lyrics—remained on fragile scraps of paper, new melodies, in keeping with Yiddish-music conventions and traditions, were created.

And, in a personalized meeting not unlike the master classes and studio critiques Dickinson music and studio-art students receive from visiting professionals, Shternshis conferred with a student privately about her senior-thesis research. Rachel Prince ’21, a double major in educational studies and Spanish who’s studying post-WWII U.S. Yiddish education programs for her senior thesis, says the chance to get individualized feedback from one of the world’s leading contemporary Jewish-history scholars was unforgettable.

“Anna was so generous to share her insight on how I should shape my research, which authors to look at, and which key terms to include,” says Prince, who’s now taking notes on the Yiddish Glory concert, which she’ll fold into her research. “I am grateful that Dickinson was able to host this residency.”

With email consultations, Zoomed classroom visits and the livestreamed performance, this residency looked markedly different than it would have in previous years—and different from the two recent residencies Korolenko served at Dickinson. But the essential benefits remain.

“Residencies are always a gift to the campus, because they bring all of us—students and faculty—into contact with some of the best minds and artists of our time,” says Wlodarski, who coordinated the Yiddish Glory residency. “For that reason, we were determined to offer a virtual residency experience for our community, to demonstrate that our worlds could still be rich and interactive, despite the limitations of the pandemic.”

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published April 2, 2021