Dickinson College Professors Publish Research on the Microbiome and Climate Change

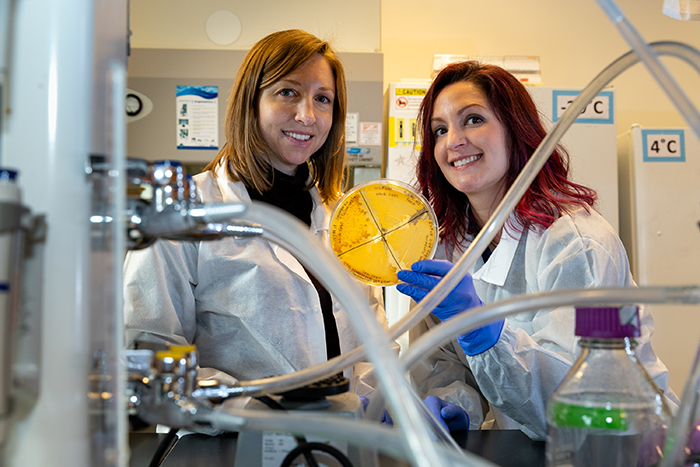

Data collected by a student-faculty research team led by Kristin Strock (left) and Dana Somers has implications for methane emissions from Arctic lakes. Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

Data has implications for Arctic-lake methane emissions

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

The microbiome is a hot topic in science writing these days, and we’re only just beginning to discover how profoundly it influences our lives. Two Dickinson professors took an interdisciplinary approach to the subject and its implications on climate science, and their work was recently published in a major journal.

Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Kristin Strock, an expert in aquatic ecology, researches the chemical changes in Arctic environments and the factors that affect them. Assistant Professor of Biology Dana Somers, an expert in genome sequencing, focuses on evolution and microbial biology. Soon after each began working at Dickinson, they discovered an overlapping research interest—how the microbiomes in Artic lakes are changing, and what the microbes’ functional processes are.

“We know that microbes play a really important role in changing how carbon is available and how nutrients are available, and carbon plays an important role in climate change,” says Strock, “but no one was characterizing the microbial community [in these lakes] and figuring out how these systems work.”

Helen Schlimm '17, Max Egener '16 and Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Kristin Strock in Greenland, 2015.

Teamwork on the tundra

The project began with a student-faculty research trip to Greenland. Strock collected shallow- and deeper-water samples from two plateau lakes, two ice sheets and two inland lakes, along with former environmental science major Helen Schlimm ’17 (now a community-science specialist with ALLARM) and former environmental science major Max Egener ’16 (now a science writer and reporter living in Portland, Oregon).

The crew couldn’t have known in advance whether they’d be able to access their desired research sites, since lakes that were free-flowing the summer before might still be iced up that year, and roads previously accessible via daylong hikes and helicopter rides might no longer be. And sure enough, Egener’s GPS and navigation skills came in handy when the group had to rework their plans on the fly.

Another snag: The team was using a new technique to filter and capture water samples. When it became clear that they’d need either more power or more time to process the samples than anticipated, Schlimm stepped up, working through several procedural problems until she found one that would do.

Max Egener '16 collects water samples on a Greenland lake.

'Interesting patterns'

In Greenland, the field work team placed the samples in a solution that prevents the bacteria from breaking down, effectively freezing them in time. Back in Carlisle, they handed the samples to Somers, who put them in a deep freeze. And when combined with preliminary samples collected by Strock, the lab work could begin.

Somers worked with biology major Kaylee Mueller ’16 (now a Boston-based scientist and science writer) to process the samples, extracting DNA and RNA from each microbe. She then sent the material to a lab, and in return, received a huge data set, which she tackled during her sabbatical year. Months of computational analysis later, all of the bacterial species present were identified.

The research team found interesting patterns, lake to lake, in which microbes were present—including microbes that can make methane and microbes that can consume it.

“It’s too preliminary to make predictions, but changing methane levels is definitely something we care about in terms of climate,” Somers says, explaining that methane plays a key role in climate change and that understanding these microbial processes can help us understand environmental patterns.

The researchers also noted that differences in the microbe communities correlated with geographical differences and the presence of substances like oxygen, carbon and nitrogen, and that some lakes are experiencing dramatic changes in methane levels over time.

Strock and Somers recently published their findings in the December 2019 issue of Microbial Ecology, and they look forward to continuing their work.

“What’s interesting to me is that it’s truly an interdisciplinary project,” says Strock, noting that students studying environmental studies, environmental science and biology have contributed so far. “It’s also, truly, a team effort, every step of the way.”

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published January 23, 2020