Dickinson College Research Team Explores ‘Stay-Behinds’ in Rural China

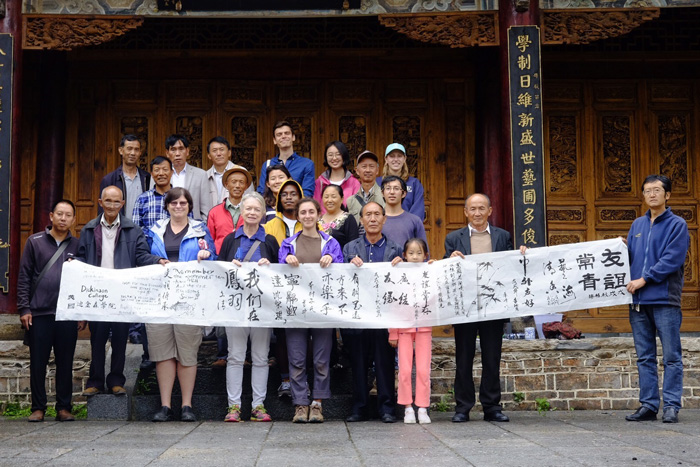

The group's collaborative calligraphy project on full display.

In the wake of mass out-migration, what happens to rural Chinese villages?

by Tony Moore

Considering China has four of the world’s 10 largest cities—and more than 100 cities with a million or more residents—the largest nation on Earth has a sharply lower percentage of people living in its cities (54 percent) than does the average developed nation (80 percent). But an ongoing trend has seen Chinese citizens fleeing rural areas for those cities.

So what happens to those rural areas as residents pick up and move, tempted by the economic benefits of the big city? China, with its 1.4 billion residents, has been finding out for the last few decades. And the migration rate will only become more striking, as China’s National New-type Urbanization Plan—set in motion in 2014—aims to move 100 million people from the country's farming regions into cities by 2020 and 250 million by 2026.

This influx of people into cities is seen as spurring economic growth and prosperity for the people moving to urban areas—and to those left behind, via remittances they receive from the departed. But it’s these “stay-behinds,” left in rural areas in the wake of the exodus, who don’t often end up under researchers’ microscopes.

The way in

In 2014, Dickinson College faculty—among them Professor of Anthropology Ann Hill—visited a small village in the upland area of the Bai ethnic minority through a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation’s Luce Initiative on Asian Studies and the Environment.

“Perhaps as many as a third of the villagers had left the village for work in nearby urban centers,” says Hill, a cultural anthropologist whose work often focuses on China. “Yet this small village, unlike many rural villages in China described in the social science literature on migration, seemed to be thriving. I wondered if this village was an exception to the general trend of the ‘hollowing out’ of rural China and if so, why?”

To study the issue, Hill and Susan Rose, the Charles A. Dana Professor of Sociology and director of the Community Studies Center, recently led a group of six Dickinson students and Dickinson’s farm manager, Matt Steiman, on a three-week exploratory research trip to China’s Yunnan Province, fully funded by an Asia Network Freeman grant. Working in three overlapping teams focused on topics of cultural sustainability, agriculture and changing family and gender dynamics, the group focused its attention on Fengyu, an 8,000-resident Bai ethnic minority village in Yunnan Province, where large-scale out-migration began more than 10 years ago.

“The migrants tend to leave their children behind with their grandparents since they are not eligible for many social services or education for their children in the cities, and often the much higher cost of living in the cities prohibits bringing the whole family,” says Rose, who has co-directed a number of global Mosaics focusing on the impact of migration on both the sending and receiving communities. She notes that while many Chinese villages are being hallowed out by migration, Fengyu still feels vibrant in the face of major changes. “Remittances—the money the migrants are sending back—are being used for new house construction that is intermixed with older structures and a few collective projects such as the building of new temples.”

Food systems and new traditions

Out-migration may in fact be economically beneficial to both those who leave, through better paying jobs, and the villages they leave behind, through funds sent back to develop various projects—and workers often return or migrate back and forth.

But beyond economics, other elements are in play.

“As a student worker at the college farm and a food studies student, I am particularly interested in the crops of this area and the food systems of which they are a part,” says Rachel Gross ’19 (environmental studies) in the project’s blog, explaining that the area traditionally produced rice and rape seed but has shifted to high-yield corn and blueberries. Gross writes that despite widespread societal change in Fengyu, the “stay-behinds” have shown a remarkable amount of resiliency and adaptability, with the community’s dynamic elderly women taking charge, doing “everything from farm work, child care and religious upkeep to cultural dancing and cooking. In the face of outmigration, the Bai community in Fengyu stays vibrant because of their active community, in part pushed forward by the steadfast participation of elderly women.”

The value of immersion

Although they were accompanied by two translators—one a graduate student in anthropology and one a librarian at Yunnan University—students often needed to find their own ways into the cultures and people of the region, developing research skills through immersion in communities from Fengyu to Kunming to Dali.

“Our cross-cultural interpretation and communication skills are of continual importance, from the most basic of interactions to collaboration with our translators,” writes Pema Tashi ’20 (American studies; Chinese minor) on the project’s blog. Tashi notes that she went into the project apprehensive about trying out her burgeoning Chinese language skills with the local population, but as immersive, trial-by-fire experiences often do, the time spent in Fengyu made her more confident by the end. “The people of Fengyu gave me the space to build my confidence. I have always internalized the daunting characteristics often associated with learning the Chinese language. … [But] on top of leaving Yunnan with my first taste of field research, I have also left more prepared than ever to start my semester abroad studying Chinese at Peking University in Beijing.”

Transferrable knowledge

While no hard-and-fast conclusions about the village’s ability to adapt in the face of out-migration could be made in three short weeks, signs of cultural and economic adaptation were everywhere. And maybe the most important conclusion reached was that the research trip, and the lessons learned, was itself as valuable as hard data, an endeavor that will serve as an inspiration and blueprint for those down the road.

“Our fieldwork over the past few weeks has been an illuminating experience—on a personal and on an academic level,” writes Alexander Bossakov ’20 (international studies). “The relationships that were at the center of our work most certainly constitute a learning experience. … Unsurprisingly, what all of us got from the fieldwork is transferrable to almost any professional path each of us could plan to undertake.”

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published October 12, 2018