A Place at the Table

From left: Edgar Estrada ’18, Janel Pineda ’18, Armando Moreno ’20 and Jennifer Zapata ’17 in front of the Social Justice House.

by Alejandro Heredia ’16

It’s no secret that the U.S. is in the midst of a demographic revolution, with all of its institutions—social, political and educational—adjusting to change in varying degrees. And with the increase of the national Latino population comes an increase in Latino students attending colleges and universities. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2001, only a little over half (51.7 percent) of recent high school graduates who identified as Latino/Hispanic went to a two-year or four-year college or university; in 2012, 69 percent were attending college.

At Dickinson, Latino students are the largest population of domestic students of color and make up about 7 percent of the student body. They are engaged in all aspects of college life—from the sciences to the arts, from leadership roles in organizations like MANdatory, Exiled Poetry Society and the Center for Sustainability Education to honor societies Wheel and Chain and Scroll and Key.

They are Posse Scholars, Schuler Scholars and recipients of the Questbridge College Match Scholarship. They have garnered Fulbright awards, graduate degrees and high-level positions in the professions of their choice. Their experiences are wide-ranging—some positive, some negative—and many of them point to how their struggles have allowed them to grow in unexpected ways and to contribute significantly to Dickinson’s social and academic environment.

Complex identities

Many Latino Dickinsonians are first-generation college students and come from immigrant households, often in communities made up of predominately working-class families. Edgar Estrada ’18 says that young Latino men like him aren’t expected to go to college, much less a private institution like Dickinson.

“I thought I would be working in construction or something like that, because that’s what most high schoolers from my area do,” says Estrada, who hails from Los Angeles. “They just work in construction or go into the military.”

Several Scroll and Key members, including Alejandro Heredia ’16 (second from right, bottom row) at the 2015 tapping ceremony.

Although transitioning from a working-class environment in southern California during his first year at Dickinson was difficult, he says, the values and support he received from his family helped him to push through his insecurities. “My mom always told me that my education was very important, but it wasn’t until I came to Dickinson that I realized how important it was—not only to me, but also to her,” he says. “Keeping her sacrifices in mind really helped me to stay grounded and focused.”

Estiven Rodriguez ’18, who emigrated from the Dominican Republic when he was 9, had attended the Washington Heights Expeditionary Learning School (WHEELS). Not long after he was accepted to Dickinson in spring 2014, he visited Washington, D.C., for the College Opportunity Summit, where President Barack Obama singled out Rodriguez’s success story. Obama spoke of Rodriguez’s experiences migrating to the United States, his journey navigating his education while learning English and how he was accepted to Dickinson on a full scholarship through the Posse Foundation.

For Rodriguez, the pressure to succeed once he arrived at Dickinson was unprecedented. But he notes how he was able to tap into his immigrant experience as a source of strength. “Going from New York City to Dickinson was hard,” he recalls. “But thinking about my experience moving from Santo Domingo to New York, that’s completely different. It prepared me.”

As a Dominican Afro-Latina, Jennifer Zapata ’17 has spent time during her college experience working to understand her complex identity and trying to unpack her African ancestry, while finding comfort in who she is in addition to her identities.

“I’m aware of where I’ve come from and how that has shaped my perspective of the world, and all I want to do is learn more, know more. Why are things the way they are? Why do people feel the need to identify with these social boundaries?” she asks. “I’m a neuroscience and philosophy double major. I’m asking all these whys. That’s who I am. I say Afro-Latina, because if I had to put myself into a box, it would be that.”

Finding community

Despite their academic and extra-curricular success, Latinos can still struggle with finding community and with fitting in, especially those in the vanguard of diversity initiatives. Glenda Garcia ’09, a member of the first Los Angeles Posse at Dickinson and who went on to garner a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship in Thailand, recalls that she was often the only Latina in the classroom, which created a distance between her and her peers.

Valeria Carranza ’09 and Joyce Bylander during Alumni Weekend 2015.

“In a classroom being Latina definitely made me stand out because I was able to speak to a lot of the experiences that people would read about in the books,” she says. “But because I was able to put so much narrative to what people were reading, sometimes they would feel intimidated by my experiences.”

That discomfort moves in both directions. Data from a student-engagement survey conducted last fall revealed that Latina women, along with black women, experience the lowest satisfaction rates in terms of “Campus Fit and Climate.”

“General climate refers to the broad sense of student attitudes and behaviors on campus that influence student experience on a general level,” explains Jason Rivera, director of institutional research. “It’s not necessarily specific to only social settings or classroom settings but all, broad settings while at Dickinson.”

Last year, when a few white students posted photos on Instagram of themselves wearing sombreros at an off-campus party, with the caption, “We promise we have our green cards,” members of the Social Justice House (SOJO) launched a campuswide dialogue to address the campus climate.

“I think a lot of people just aren’t sensitive or aware of what immigrant experiences are like or how these ideas perpetuate anti-Latino sentiment,” says Janel Pineda ’18.

More than 100 students from all backgrounds huddled in the cramped SOJO living room to discuss what kind of impact such actions might have. Pineda, one of the students who led the dialogue, says that although it was a difficult experience for Latino students, she was able to turn the conversation toward positive change.

“In sharing my own experience as the daughter of Salvadoran immigrants, I was able to use story as a means of empowering my Latinidad,” Pineda says. “The exchange of stories and perspectives [during the meeting] was ultimately powerful and momentous in its creation of a space to begin building understanding within our community.”

Moving forward

Valeria Carranza ’09 encourages students to continue turning instances of struggle into sources of empowerment. The daughter of Salvadoran immigrants and the first in her family to graduate from college, she is currently the executive director of the U.S. Congressional Hispanic Caucus.

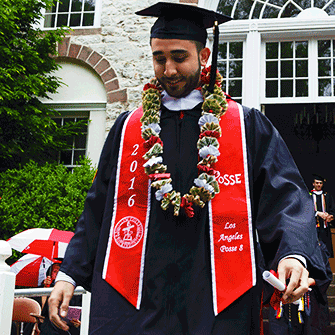

Andy Vargas ’16 steps forward during Commencement.

Carranza, who received the Outstanding Young Alumni award in 2015, was also a member of the first Los Angeles Posse at Dickinson, and she reports experiencing similar difficulties as Garcia, her fellow Posse member.

She adds that there were also great moments of joy. For example, she points to members of her sorority, Kappa Alpha Theta, who, knowing that Carranza identified as a gay woman, changed the organization’s gender policy, making it more inclusive.

She also met “amazing people” who would become friends for life. Members of her Posse were at her wedding recently, and Vice President and Dean of Student Life Joyce Bylander, who was her Posse mentor, officiated at the event.

“Dickinson offered me a snapshot of what the rest of America looks like and how difficult it can be to be brown in a sea of white,” she says. “I saw both sides of the coin, which prepared me for the American workforce that I’m a part of now. I’m able to navigate non-Latino spaces while still embracing my Latina identity.” She continues, “Embrace every little part about you, because that adds value. You’re bringing your community to the table.”

Learn more

- Summer 2016 Dickinson Magazine

- Diversity at Dickinson

- Latin American, Latino & Carribean Studies

- Latest News

Published July 12, 2016