Dickinson Showcases Microscope Legacy With State-of-the-Art Upgrade, Research Project

Students display the placards they created for a Waidner-Spahr exhibit of historic microscopes.

Students connect centuries of science education by pairing historical instruments with the college’s new confocal microscope

by Tony Moore

Dickinson’s scientific tradition spans centuries—and now students are experiencing that history firsthand while also working with cutting-edge technology.

History & the Future

Last semester, students in Charles A. Dana Professor of Biology John Henson’s Bio-Imaging Research course curated a public display of Dickinson’s historical microscope collection, with instruments dating as far back as 1740 (the college’s oldest microscope). Each group researched the history of their assigned microscope and created informational placards that accompanied the historical microscopes displayed in the library late last semester.

At the same time, the class was among the first to work with Dickinson’s newest acquisition: a state-of-the-art Andor BC43 benchtop confocal microscope, purchased with a $150,000 grant from the George I. Alden Trust and an alumni gift. The microscope was installed in February, coinciding with the start of the course.

In essence, a confocal microscope has the capabilities to filter out light that is out-of-focus and enables researchers to reach incredibly high-resolution images that focus on a thin plane/cross-section of the cells being studied. Dickinson was among the first liberal-arts colleges in Pennsylvania to obtain one, back in 2003.

“It allows us to take the next leap forward,” says Henson, “and the fact that students get to experience the history alongside the innovation is really remarkable.”

Students like Scott Shim ’26 (biochemistry & molecular biology) have been using the microscope for months now, and he doesn’t mince words.

“Confocal microscopy is such an amazing advancement in the biological field, and it truly has been such a blessing to the department and institution,” he says. “What a treat it has been to get to use the confocal.”

Use Case

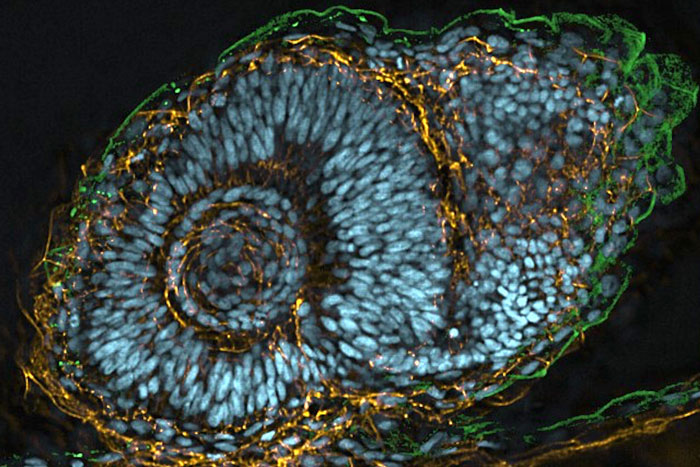

Students quickly put the instrument to the test, conducting a proof-of-principle project that produced striking images of, for example, a developing zebrafish embryo’s eye—work they later presented at the annual Science Student Research Symposium.

“To be able to learn about a microscope then to actually see one in action was a great learning opportunity,” says Konoka Uematsu '26 (biology). “It was also my first time using a confocal microscope, which made the experience all the more exciting.”

A confocal image of a zebrafish embryo's eye, captured as part of Henson's class.

The microscope, with its sophisticated software, allows students to project the cells they’re studying in 3D, mapping out critical protein interactions in X, Y and Z planes.

“It’s often hard to have a holistic understanding that our tiny building blocks of life have an unimaginably, complex three-dimensional structure, let alone the significance of where our proteins are localized in it,” Shim says, explaining that the new microscope “has been the key instrument that creates the bridge between the conceptual frameworks we've postulated in our hypotheses—and also foundational masteries from our academics—to the reality we see unfolding under the lens!”

Meanwhile, the pairing of historic instruments and the new confocal microscope created a unique learning experience, showing students not just where science is headed but where it began.

“My group focused on a microscope that was patented in 1876, and something that surprised me was how well this seemingly outdated instrument still worked,” Uematsu continues. “Putting aside the emergence of other types of microscopy, it was interesting to see how light microscopy fundamentally hasn't changed all that much through the past 150 years of refinement and fine-tuning.”

The new microscope will serve numerous Dickinson students each year across biology, chemistry, neuroscience, physics and related fields, and it will also be made available to faculty and students at Gettysburg College and Shippensburg University.

Microscopy-based Research in the Wider World

Undergraduate research at Dickinson isn’t limited to the classroom—it extends to some of the most advanced laboratories in the world. And the addition of Dickinson’s new confocal microscope only deepens these opportunities.

A recent publication and an international meeting presentation from Henson’s National Science Foundation supported research included nine Dickinson student coauthors, highlighting the breadth of student involvement in cutting-edge bio-imaging research. The project explored the fundamental process of cell division using high-resolution microscopy, with data gathered both on campus and at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s (HHMI) Advanced Imaging Center at Janelia Research Campus, one of the world’s leading bio-imaging research institutes located outside Washington, D.C.

“My visit to the HHMI Janelia research campus was nothing short of a spectacular, with such a display of pure science!” says Shim, who adds that he and classmate Allie Hershey ’25 shamelessly ‘nerded out’ across the entire visit. “With some of the greatest microscopes in the world housed in Janelia, it was fascinating to see them run using samples from our very own lab. I cannot overstate how much our visit to the literal cutting-edge of scientific research deepened our passion for the ever-evolving field of cell biology, and it stands as one of the cornerstones of experiences as a Dickinsonian and in my career of research.”

Equipped with the Andor BC43 benchtop confocal, and combined with partnerships at external facilities like HHMI-Janelia and the National Institutes of Health, Dickinson students now have access to a full spectrum of imaging resources. And Henson emphasizes the impact this can have on student trajectories.

“Our students’ ability to train on a state-of-the-art confocal microscope provides them with a highly marketable skill—whether they’re applying to graduate or medical school or pursuing lab positions in academia or industry,” he says. “It’s transformative for our students and our curriculum.”

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published September 22, 2025