Student 3-D Model Wows Excavator of Mysterious Ancient Egyptian Ship

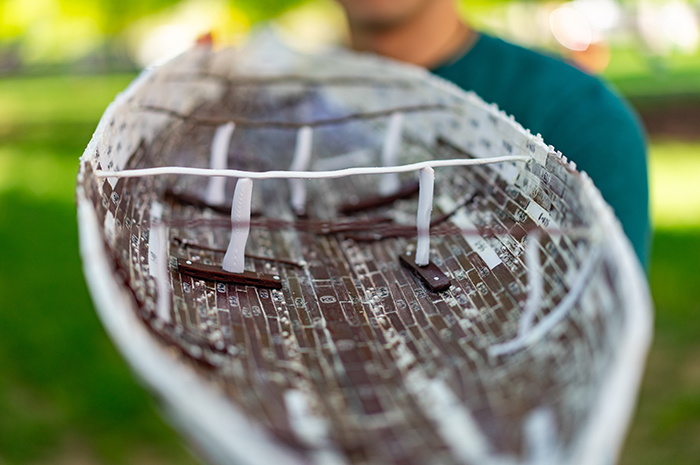

Hunter Omerzo '24's 1/30-scale replica helps answer age-old questions about a famed fifth-century B.C. vessel. Photo by Dan Loh.

Shipwreck research makes waves at Oxford

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

In the fifth century B.C., Herodotus described a riverboat so peculiar it sparked centuries of scholarly debate. The Greek historian called it a baris, and for ages no one could verify that his account was accurate or even true. That is, not until “Ship 17” blew Herodotus’ doubters right out of the water and made international news.

Now, Hunter Omerzo ’24 adds to the world’s understanding of it, as he has created the most detailed and accurate 3-D model of a baris to date. His recreation of Ship 17, sparked by a classroom assignment and created with his own 3-D printer, helps answer researchers’ questions. And soon, he’ll continue his research at Oxford University.

The case for 3-D

Omerzo, an Ohio native, is a Dickinson student-athlete, a double major in archaeology and classical studies and the recipient of Raven's Claw and C.V. Starr scholarships. He learned about the baris while translating Herodotus’ writings for a class taught by Associate Professor of Classical Studies Scott Farrington.

Omerzo painstakingly replicated each part of Ship 17 for his model. Photo by Dan Loh.

Having already dived to and learned about shipwrecks through a field-school experience, Omerzo knew that physical, 3-D models are less common in marine archaeology than their digital counterparts. And while reading about the excavation of Ship 17 in the Nile Delta, he discovered that the only 3-D baris model in existence was a rough estimation, created for a BBC documentary. Omerzo wondered if a more accurate 3-D model would help researchers better understand this mysterious ship.

“It’s sort of like how reverse engineering works,” explains Omerzo. “You can’t always tell what a certain part is for until you try to put it back together."

Expert on board!

For precise measurements, Omerzo went straight to the source. He emailed Alexander Belov, a researcher for the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology (France), which excavated Ship 17. Belov's book on the Ship 17 findings, published by the Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology, was Omerzo’s primary resource.

“Hunter set the first baris afloat since the time of Herodotus. This is a great achievement." —Alexander Belov

The expert was impressed. “I got an image of Hunter as a very keen and motivated person with a great working capacity," says Belov, who not only sent his data but also remained in touch, answering questions and offering advice. "Not every person would be so intrigued by the ancient description of a vessel and undertake such a complicated and time-consuming project.”

Complex and color-coded

Slowly and carefully, Omerzo replicated each part of Ship 17 for his 1/30-scale model, down to the tiny tendons, and weighted each section to scale. He counted 837 parts, not including pegs.

Omerzo put his 3-D-printed model to the test in Dickinson's pool. Photo provided by Hunter Omerzo.

It took weeks to create the pieces with his own 3-D printer and months to assemble the model. His first attempt was a partial recreation. His second was complete, with color-coding to differentiate surviving sections of Ship 17 from missing, damaged and obscured sections.

And then it was time to test the model in the pool.

To simulate a cargo load, Omerzo filled plastic bags with .25 kilogram of sand and added them to his mini-baris. While a thin coat of liquid rubber hadn’t waterproofed the model completely, it still floated well.

“Hunter set the first baris afloat since the time of Herodotus,” says Belov, who shared Omerzo’s findings with the marine archaeology department at Oxford University. "This is a great achievement."

But what does it mean?

Omerzo’s project provides new details about several aspects of the baris—most significantly, it shows that the design was sound. By Herodotus’ description, the baris had no frame. Instead, a single plank served as its hull, with thin, side-to-side ribs inserted into the hull planking. That skeleton-like structure provided enough support for Omerzo’s model to carry 4 kilograms of cargo.

“That was impressive, and it translated to 108 metric tons—just barely shy of Belov’s 112-metric-ton estimate,” Omerzo says. “I also got to observe how the ship sank, which is important to my current research.”

More mysteries ahead!

The end of this story marks a new beginning: Omerzo will continue his research as a master’s candidate at Oxford University. He looks forward to refining his model—this time with access to the original artifact.

Belov looks forward to learning about Omerzo’s progress. He also hopes to one day connect with Omerzo at Thonis Heracleion, the sunken city in Egypt where Ship 17 was discovered along with some 125 ancient hulls.

“It’s the greatest known cemetery of ancient ships in the world,” Belov says, “and I hope that Hunter will be able to join our excavations, because there are still so many mysteries to solve.”

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published July 16, 2024