Thinking With Benjamin Rush

Photo by Carl Socolow '77

by Christopher J. Bilodeau, Associate Professor of History

Like many Americans across the country, I was dismayed when I heard of the racial tension and violence that took place in Charlottesville, Va., this past summer. I was disheartened at seeing white supremacists with torches march to the Thomas Jefferson statue on the University of Virginia campus as they tried to claim him as one of their own. But I was encouraged at seeing a group of counterprotesters surround the statue first, defending it from what they believed was an unjust appropriation. Jefferson was, obviously, not a blameless man. He derived his wealth and lifestyle from the hundreds of African-American slaves he owned. He recognized that fact as a problem yet did nothing about it. In his writings, he implied that blacks lacked the moral and intellectual potential for republican citizenship in the new United States. How should those facts inform our thinking about Jefferson today? As Americans and human beings of the 21st century, what do we think Jefferson owes us? What do we owe Jefferson? Or, put more broadly: What do we think the Founding Fathers of the United States should do for us today?

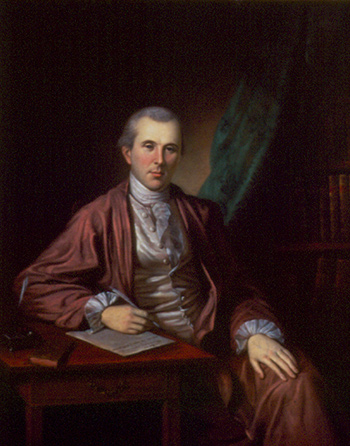

I thought about that question for quite some time while standing recently in front of the statue of another founder, Benjamin Rush, in front of Old West on the Dickinson campus. He has been someone I like to think about—and with—since I arrived at Dickinson in 2006, but this year his statue has taken on new meanings for me, as it has for other Dickinsonians, particularly when I consider his views on racial difference, on slavery and on freedom.

African-Americans in a Republic

Rush was a complicated thinker during a complicated time. His deep-seated faith in the power of rationality to dispel injustice and undeserved privilege led him to question and criticize simplistic or “common sense” notions that others might use to support tradition, hierarchy or inequality. For Rush, human beings were naturally disposed toward liberty, and liberty would naturally endow citizens with virtue. In this way, Rush was typical of those who believed in “republicanism,” the driving ideology of many revolutionary thinkers in the 1770s and 1780s. But republicanism is a broad ideology, and each republican could have different views about the same subject. Rush’s republicanism was personal and idiosyncratic, just like Jefferson’s. But unlike Jefferson, Rush believed that Africans or those of African descent were just as capable of shouldering the responsibilities of republican freedom as any white person.

“I need say hardly anything in favor of the Intellects of the Negroes, or of their capacities for virtue and happiness, although they have been supposed by some to be inferior to those of the inhabitants of Europe,” he wrote. “The accounts which travelers give of their ingenuity, humanity and strong attachments to their parents, relations, friends and country, show us that they are equal to the Europeans.” For Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, all men were created equal, including those who were enslaved.

It was slavery, for Rush, that was the problem. It alone perpetuated the false claims about racial inferiority of blacks. “All the vices which are charged upon the Negroes … are the genuine offspring of slavery, and serve as an argument to prove, that they were not intended, by Providence, for it,” he wrote. This was no small claim for Rush. Slavery was not simply an institution that at its root was unjust; slavery was a transgression against natural law and a blight against God—a serious charge for the devout Presbyterian Christian. He believed that the new nation, the first of its kind ordered around the universal truths of natural law, could not continue to maintain the scourge of slavery without some terrible reckoning. “Remember that national crimes require national punishments, and without declaring what punishment awaits this evil, you may venture to assure them that it cannot pass with impunity, unless God shall cease to be just or merciful,” he wrote. A transgression of such magnitude against the natural order of things—a natural order ordained by God—would eventually elicit a punishing response.

Abolitionism and “Black Leprosy”

As such, Rush became a committed and prominent abolitionist in Philadelphia in 1787. He began that commitment in a typically idiosyncratic way, becoming an abolitionist after a dream about the recently deceased abolitionist Quaker Anthony Benezet. He immediately joined the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society, becoming not only a powerful advocate but also an author of its new constitution and a president of the society. He supported “gradualism,” the major abolitionist position within Pennsylvania generally. On March 1, 1780, the Pennsylvania legislature passed one of the first attempts by a government in the Americas to put an end to slavery. Titled An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, the law attempted three things: It prohibited the importation of slaves into the state; it required citizens of Pennsylvania to register their slaves each year, or else the masters would be fined and the slaves freed; and it claimed that any child born in the state was free, regardless of the status of his or her parents. Rush was firmly within this tradition of gradualism, which became a model of abolitionism in northeastern states such as New York, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New Jersey. (Massachusetts passed a law in 1783 that “instantly” abolished slavery, providing the other model for states.)

But as I said, Rush was a complicated thinker, and this fairly straightforward narrative of his views on African-Americans, slavery and abolitionism is complicated by other evidence. Rush was a gradualist abolitionist, true, but what about William Grubber, a child slave whom Rush bought and owned until 1794? Purchasing slave children with the purpose of emancipating them was a common practice among gradualists. But Rush didn’t manumit him immediately; in fact, he manumitted him only after receiving, in his words, “a just compensation for my having paid for him the full price of a slave for life.” Scholars have speculated that Rush must have purchased him in the early- to mid-1770s, or roughly about the time he wrote his critique of slavery, Address to the Inhabitants of British Settlements in America, upon Slavekeeping (1773). Did he feel conflicted about voicing his strident views against slavery while owning another human being? Rush himself offers little comment in any of his writings.

And the questions don’t end there. Rush’s views on race—a term undergoing radical shifts in definition at precisely this revolutionary moment—indicate a man who liked to blend his interests in physical science, political science and theology in a particularly dizzying, late-18th-century mix. Rush was eager to prove that all human beings “descended from one pair,” Adam and Eve. But if that was the case, why did Africans and African-Americans look so different from Europeans? He concluded that a variant of leprosy caused blackness in skin color. A cure for leprosy, therefore, would change Africans’ skin color “back” to white, the skin color of Adam and Eve. Such an argument would allow Rush to support his Christian creationism, undermine those who argued that blacks were “naturally” disposed to enslavement, and provide for the possibility that African-Americans could assimilate fully as virtuous republican citizens into the new nation. And he justified this claim in part on the work of another scientist who applied muriatic acid, a harsh and corrosive relative of hydrochloric acid, to the skin and hair of an African-American man. Yet he made no mention of the glaring moral problems with that practice.

Regardless, his claims of “black leprosy” were deemed controversial during the early republic. They are patently preposterous to us today. But they were controversial within a particular historical environment. Rush believed that universal laws governed not only nature, but also people and their interactions. Laws of politics, laws of society: they were all laws of nature, and they were all immutable. But how did they fit together? Rush, more than most republican thinkers during the late 18th century, attempted to connect numerous fields of thought and knowledge to uncover universal laws that he believed made the new United States a radical experiment in freedom and liberty. Obviously, that desire led him down some pretty questionable paths.

Image courtesy of the Winterthur Museum.

Rush and American Indians

Rush’s ideas about the original inhabitants of North America, American Indians, are just as discordant to our 21st-century ears. In An Account of the Vices Peculiar to the Indians of North America, he broadly criticized Indians for the lives they led and their lack of contributions to society. He claimed that Indians were characterized by uncleanliness, drunkenness, gluttony, treachery and a host of other vices. He believed them cruel, especially in the ways they degraded their women, which Rush counted as their worst vice. He conceded that they loved liberty, but their liberty was deficient because of their ignorance of the influence of property. For republicans like Rush, property was the cornerstone of the new nation; it made people independent, and independence led to virtue; it was the necessary bulwark against tyranny. Without it, no one could be free.

Rush seems to imply in these writings that Indians could not survive in a republic. As slavery was doomed by the natural human inclination toward freedom, so too were Indians doomed by the natural human inclination toward property, and therefore only whites and blacks would thrive within this new, modern, republican world.

A “Useful,” Republican Education

But as I contemplated these sobering thoughts about Rush, thinking about him in his world and ours, I concluded that these were not the last words, nor even apt words, to end any discussion of him. For as I looked up and considered his statue, I did so on the grounds of a college he founded. That’s important. Rush was an 18th-century idealist, but one firmly grounded in the twin pillars of scientific method and Christian religion. In our age, we tend to think of these two things as separate, even incongruous; in fact, they were already becoming separated in his age too. But Rush’s faith in both a Christian God and in the power of Enlightenment thought compelled him to invest in republican education, especially in the founding of Dickinson College.

It was an education in part committed to those who had been previously denied it. If someone could prove themselves worthy of its rigors and insights, then that person was welcomed. The role of education was to mold men and women to take on roles of republican responsibility and leadership, to lead a young nation beyond where it was in 1783, when the college was chartered, to futures unknown. Rush certainly was a part of his 18th-century world, but his emphasis on education showed he strove to transcend it. He worked to put in place an institution that allowed others—including those of us who teach and learn at the college now—to transcend their worlds as well. I think that if the statue of Rush stands for anything, it stands for that: a legacy of intellectual growth, of critique and self-critique, of the pursuit of knowledge and meaning within an institution that understands that pursuit as restless and never-ending.

It is an aspirational vision, one that purports that the days to come can be better than the ones that came before, but only if individuals engage in rigorous debate, to upend traditions and common-sense notions that no longer have purchase in a society that strives to be free and dynamic. Or, as it is written in Dickinson’s charter, “to promote and encourage…every attempt to disseminate and promote the growth of useful knowledge.” In this way, Rush laid out the challenge, and it remains for us to maintain it, even as we maintain it in ways that Rush wouldn’t have approved of or even recognized. To my mind, that is what Benjamin Rush does for us today.

Read more from the fall 2017 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published November 3, 2017