Worst Election Year Ever

by Robert Strauss

Now a condominium building, Music Fund Hall, the first New World theatre to be built specifically for concerts, sits near 8th Street on Locust in Philadelphia. In 1856, it held the presidential convention for the newly formed Republican Party. A couple months before, four blocks to the northwest, a similar first presidential convention for the nascent American, or “Know-Nothing,” Party took place at the old National Hall. Three blocks south of that, and five blocks west of Music Fund Hall, is the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the keepers of the majority of the papers of the Democratic Party standard-bearer that year, James Buchanan, a Dickinson graduate (class of 1809) and the only presidential candidate ever from Pennsylvania. That the three major parties all had a Center City Philadelphia provenance in 1856 may be coincidence, but the presidential race that year was among the strangest, and most important, in American history.

The Republicans and Know-Nothings (the nickname comes from the secretive nature of the party—its adherents would say they “know nothing” when asked about the party’s dealings) both emerged from the ashes of the Whig Party. The Whigs held the presidency only three years before, but their drubbing in the 1852 election and the deaths of their senatorial stars—Henry Clay and Daniel Webster—both just before that election caused it to fall apart.

Those who held views favoring the abolition or at least the limitation of slavery drifted to the Republican Party, started mostly by those in the relatively new Western states. The most prominent of the Whigs-turned-Republicans was Sen. William Seward of New York, but he took himself out of the presidential sweepstakes, mostly because he did not think the party could win its first time around. As German and Irish Catholics immigrated to the U.S. in the mid-19th century, nativists felt threatened, and from that the Know-Nothing Party got its start.

Both, though, were parties without someone at the top. Millard Fillmore, that last Whig president, felt short-changed when the Whigs bypassed him for the 1852 nomination, so when the Know-Nothings approached him— despite his never having had anti-immigrant or nativist leanings—he jumped at the chance to get back to the White House.

The Republicans, who were never going to get on the ballot in many Southern states, chose one of the great celebrities of his time, John C. Fremont. Fremont and his guide, Kit Carson, had laid out the pathways to California and the Pacific in four major expeditions in the 1840s and 1850s. Meanwhile, incumbent President Franklin Pierce was shunted to the sidelines, primarily over his mishandling of whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free state or a slave state and how that would play out with future states. After 16 ballots at the Democratic convention in Cincinnati, the party gave the top spot to an old war horse, James Buchanan.

Buchanan had perhaps the best governmental resumé, then and now. He had been a state legislator, a U.S. House member, a U.S. senator, minister to Russia and to Great Britain and secretary of state. He reportedly had been offered U.S. Supreme Court seats by two presidents.

But his resumé also laid bare that he was mired in past politics. He was 65 at his inauguration in a country where living until 40 was an achievement. He was nicknamed “Old Buck” and was of the ilk called a “Doughface,” a Northerner whose face was so mushy he was molded into the dough of Southern (i.e., pro-slavery) thought.

“The stakes were high in 1856,” says Michael Birkner, a history professor at Gettysburg College and co-editor of James Buchanan and the Coming of the Civil War (2013). “The Democrats outmaneuvered the Whigs in the South, where the Whigs just could not advocate the elimination of slavery. The Republicans could not yet be a national party, but the tension around slavery was really the only main issue.”

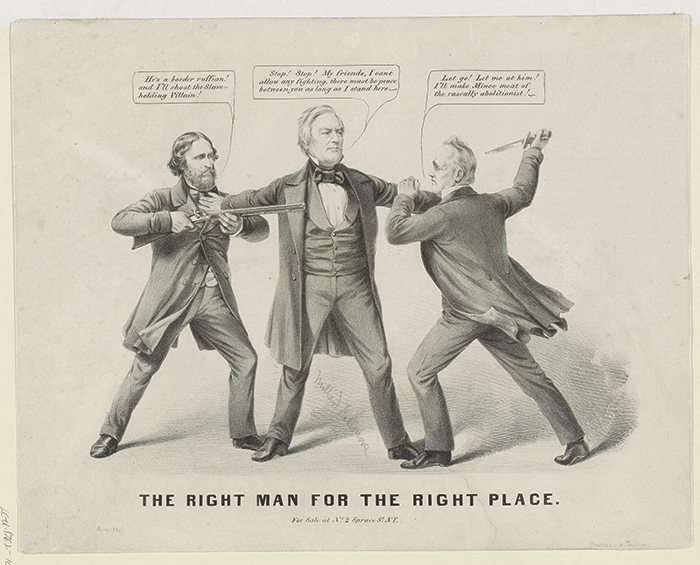

The campaign was ruthless, even though none of the candidates, as was usual in 19th-century elections, gave a stump speech or traveled anywhere, leaving their campaign to surrogates and, sometimes, letters to publications. For instance, Buchanan’s sisterin-law’s brother was the famous songwriter Stephen Foster, whose family was prominent in Pittsburgh politics. Foster gladly wrote campaign songs for Buchanan, but copyright laws being what they were then—pretty non-existent—the Fremont campaign used Foster melodies like “Old Kentucky Home” for pro-Republican campaign songs, perhaps trying to foster the idea that even Buchanan’s in-law was against him.

Meanwhile, the Know-Nothings, who tried to compete in every state, getting on ballots in the South when the anti-slavery Republicans couldn’t, stoked anti-immigrant subterfuge and even riots in some cities. In the end, however, Buchanan won all the Southern states, plus a few in the North and in the West, including his home state of Pennsylvania. Fillmore won Maryland and Fremont won 11 mostly northeastern states.

Almost immediately, Buchanan fed his own demise. In the interim between election and inauguration, he surreptitiously influenced the outcome of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott v. Sanford case. The decision essentially negated all the previous anti-slavery compromises, making the institution legal across the land and denying citizenship to all African Americans—slave and free.

As president, Buchanan managed to make the wrong choice every time it mattered. He advocated buying Cuba in hopes of making it a slave state to equalize the free ones. In Kansas, his hesitation caused a bloody border war. And in the last months of Buchanan’s term, six states seceded, a move he said he could not stop by his interpretation of the Constitution.

“I guess you could say Buchanan was a good candidate in that he won,” says Matthew Pinsker, Brian C. Pohanka Chair in American Civil War History at Dickinson and director of House Divided research tool for K-12 educators. “Despite his experience, he was not the man to lead the nation at that particular time. It was a major consequential election, even if it ended up producing a pretty bad president.”

Robert Strauss is the author of Worst. President. Ever: James Buchanan, the POTUS Rating Game and the Legacy of the Least Lesser Presidents. He is a journalist and historian and has written for Sports Illustrated, The New York Times and the Philadelphia Daily News, among many others.

Learn More

Published October 18, 2016