Dialogue, Discovery & Religious Life

Illustration of Donna Hughes, director of community service & religious life, by Marc Burckhardt.

Donna Hughes opens doors to interfaith conversations and explorations

by Martin de Bourmont ’14

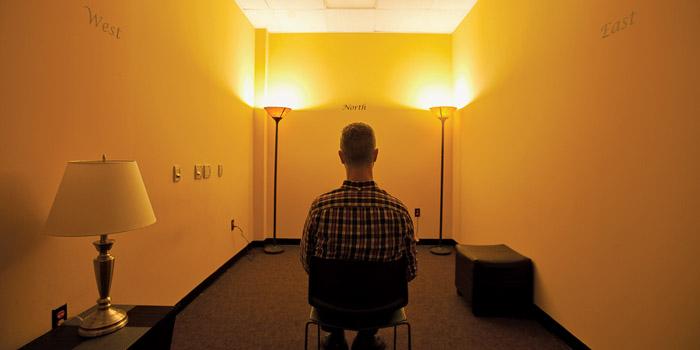

In the lower level of the Holland Union Building you will find a white door with a small rectangular window. A plaque identifies it as the door to Dickinson’s meditation room. You will not find much behind it. At the center of the room is a table, fitted with a lone, empty drawer. A bookcase stands in the corner, offering visitors a collection of Bibles and an introductory text on the Baha’i faith. Below these tomes are two neatly folded prayer rugs. You can sit either on the floor or on one of the chairs in the room’s left corner.

Once seated, you will look up at the room’s dull beige walls, unremarkable except for the corresponding cardinal direction written in bold black lettering on each of their faces.

The room’s blandness should not be taken as a reflection of the college’s spiritual poverty, however. Quite the opposite: The room’s plainness reveals an environment that encourages diversity and contemplation, where reflection is prompted by discovery and conversation, not visceral reactions to the flamboyance of sectarian icons.

More important, as a liberal-arts institution committed to upholding diversity of all kinds, Dickinson strives to embrace the spiritual and religious practices of all its students. And nowhere is this intention more clear than in the Office of Community Service & Religious Life.

Dickinson's meditation room. Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

When Donna Hughes, director of community service & religious life, arrived at Dickinson in 2013, she knew she wanted to build her programming based on a student-centered approach. An ordained Methodist minister with substantial experience working closely with students on college campuses, Hughes sees Dickinson as an ideal environment to build a model interfaith program.

“What I find really fascinating at Dickinson is the openness of students to spiritual things, not necessarily religious things, to explore,” says Hughes. “When we had a meditation workshop, 19 students showed up on a Saturday morning. This is probably the most spiritually open of any place I’ve ever worked.”

Hughes believes that creating a public forum for worship and interfaith discussion on campus will prove durable and attractive — even to those who have shied away from religion and spirituality in the past or have felt alienated from it. “Just by the nature of what I do in religious life, there are students who are uncomfortable, as well as faculty and staff,” she explains. “As I develop relationships with students doing community service, here in the office or doing other things on campus, that allows the opening for people to feel like they could actually explore something religious or spiritual.”

To that end, Hughes has relied on four student leaders to help her with outreach and programming: Jiyeong “Faith” Park ’16, a member of the leadership team for the Dickinson Christian Fellowship; Shayna Solomon ’16, president of Hillel; Asir Saeed ’16, treasurer of the Muslim Students Association; and Emma Weinstein ’16, also a member of Hillel. As leaders in their own religious groups, they initiate interfaith discussions on meaning, understanding, purpose and faith. During meetings with Hughes, the students discuss how they experience spirituality in their lives as well as how they share those experiences with other students.

They also help organize and lead interfaith service trips, including one last fall to Philadelphia that included working in a soup kitchen, a thrift shop, the SHARE Food Project and Stop Hunger Now. For the 13 student participants and four student leaders, part of the trip included attending services in places of worship. “We visited a mosque, a temple and a church and then did community service,” explains Saeed. “And then every night, we came together and talked about what we saw, what we thought about what we saw — and not just the community-service aspect, but what we thought about what we observed at the religious services, what was striking, what we learned.”

Hughes and her team also are working to increase awareness of minority religious groups. “We are trying to encourage some of the students who practice Buddhism, Taoism or Shintoism to come and discuss their experience,” Park says. “It’s a challenge. The student leaders are going to have to do a lot of personal invitation.”

Nor does the outreach program limit itself to community service or initiating conversations between believers. “We also want to serve nonreligious students,” says Solomon. “That’s a difference from the past.”

One way of connecting with nonbelievers is to host discussions with the help of the Secular Students Union (SSU). “We did a panel discussion with some students of different religious backgrounds; Professor of Religion Ted Pulcini, who is also a Greek Orthodox priest; and the SSU about the relationship between religion and science. It’s a controversial subject, but it was a really civil, intellectual discussion,” says Solomon.

That deliberate inclusiveness was especially visible at Dickinson’s World Religions Festival, an event organized by the student leaders in April. Held on Britton Plaza, the festival featured representatives from different religions, spiritual philosophies and cultures.

At each table, students could find something visual, informative or interactive — ranging from games and calligraphy tutorials to maps and dioramas. The participants did not aim to convince, only to share — to tell stories and reveal the beauty and care that lies at the core of a believer’s expressions of faith. The students forgot the meditation room that evening, exchanging silent contemplation for conversation in the spring breeze.

The position of director of community service and religious life is supported by the United Methodist Church.

Learn more

Read more from the summer 2014 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Published July 22, 2014