Going the Distance

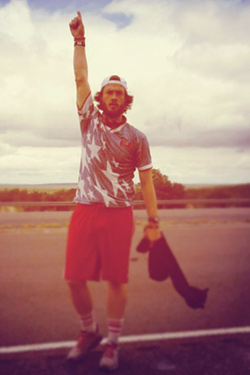

Alex Forte ’03 is a former All-American Red Devil cross country runner who’s taken up competitive bicycling and as earned several podium finishes in the USA Cycling Cyclocross National Championships. Photo by Jason Calderon.

by Matt Getty

Kirsten Nixa Sabia ’92 runs through the dark, humid Florida night on a long stretch of highway known as Alligator Alley. The steady rhythm of her sneakers hitting the pavement pulls her forward. Her headlamp beam cuts through the pitch black, spotlighting the road, showing her the way forward. She hopes the light doesn’t catch a tail, a snout, a pair of reptilian eyes.

Then it happens. She’s on mile two of a 12-mile leg of her first Ragnar—an overnight relay race combining long-distance running, sleep deprivation and exotic locations—when that headlamp goes out. Now there’s only darkness. Only darkness and 10 miles to go. Only darkness and those unseen tails, snouts and eyes.

Maggie Peeke ’11 braces herself against a wind that feels like it’s got teeth. She’s halfway to the peak of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington, known for having the worst weather on the planet. It’s February, and the wind is living up to its reputation, proving its point, telling her to turn back.

It’s minus 70 with the wind chill, and that last gust was so strong, she knows if she wasn’t weighed down by her pack, it would have swept her right off the mountain.

But that’s not the problem. The problem is her goggles. Or rather that her breath has frozen over on her goggles. Or rather that she can’t see past the thick sheet of ice, inches in front of her eyes.

Still, Peeke didn’t come out here to get halfway to the summit. Lifting her leg tentatively, she feels for a foothold in front of her, takes a deep breath, steps forward.

Richard Goldberg ’59 stands in the assembly area for the New York City Marathon, waiting for the bus that will take him to the starting line. Next to him, his wife is crying. He looks her in her tear-slicked eyes, takes her by the hand and tells her it’s going to be OK.

But he knows she isn’t being ridiculous. He is 55 years old. When he turned 50, he was in such poor shape he couldn’t run 100 yards. Now he’s running his first marathon, and as the bus lurches to a stop before them, his wife is convinced that she will never see him alive again.

Goldberg walks toward the bus, adjusting the number pinned to his shirt. He gives his wife a wave, takes a deep breath and prepares for the race.

As extreme endurance events such as marathons, triathlons, Tough Mudders, mountain climbing and ultra-marathons have proliferated over the past decade, more and more people from all walks of life are lacing up their sneakers and boots to push themselves to their limits. And Dickinsonians have been on the forefront. But looking over the previous scenarios, it’s hard not to come back to one central question—why?

For Albie Masland ’06, who did the equivalent of a marathon a day when he ran 3,025 miles across the country to raise money for veterans through the Travis Manion Foundation in 2012, it’s all about the “edge.”

“I think everyone has an edge,” says Masland, who enjoyed that run so much he ran across half the country two years later. “It just depends on whether that edge is a butter knife or something you sharpen on a regular basis. You can sit back and keep a dull edge, just be complacent where you are, but I know I’m at my best when I’m finding new ways to push myself, new ways to sharpen that edge.”

Alex Forte ’03 knows that edge well. A former All-American Red Devil cross country runner who’s taken up competitive bicycling, she’s earned several podium finishes in the USA Cycling Cyclocross National Championships.

“It’s the craziest coolest thing you’re ever going to do—like doing an obstacle course on a bike,” she says of the cross-country biking sport that requires you to ascend vertical mud slopes, carry your bike over logs and jockey for position on narrow mud trails, your tires inches from your competitors’. “It’s like being a kid again, when you would just hop on your bike and go splashing through mud puddles.”

Only in this case being a kid again requires tons of serious training. That means five days of riding 30 to 50 miles a day, coupled with distance running to build endurance. Then as she gets closer to cyclocross season, it’s shorter, more intense rides, strength training and a lot of planning for the courses, which can be as mentally grueling as they are physically.

“It’s all about pushing my body to the limit, but it’s not just about being prepared physically—you also have to be prepared mentally,” explains the Dickinson Athletics Hall of Fame inductee. “You have to know the terrain, but then the terrain changes each lap. One lap might be smooth, but the next there could be ruts carved in the mud from the other riders. It’s like constantly solving a puzzle—at high speed.”

Like Forte, Nick Karwoski ’10 knows a lot about pushing his body and mind to the limit. Also an All-American runner at Dickinson, Karwoski was tapped by the USA Triathlon Collegiate Recruitment Program six years after graduating to compete for the U.S. national triathlon team. That meant competing in nearly 20 triathlons around the world from 2014 to 2016 as well as three training sessions each day for the better part of three years.

“You know it’s going to hurt, but you have to keep going,” says Karwoski, who rose to be ranked ninth in the sport, just missing the cut for the 2016 Olympics. “You have to know how to manage the pain, and at this level, it’s all very data driven. You have all these metrics for your resting heart rate, your max heart rate, your power on the bike. You have to know what your 90 percent is, what your 100 percent is, because you can push it at 100 percent at some points, but you have to know what’s left in the tank. The most fit athlete doesn’t always win—the smartest one does.”

A Grueling Hobby

You don’t have to compete at the professional level to become obsessed with sharpening that edge. Rob Raub ’96 and Ty Saini ’93 have trained for and competed in numerous Ironman triathlons while managing successful careers as a medical marketing professional and orthodontist, respectively.

And the time commitment goes well beyond the 10 to 13 hours it takes to complete each race, which consists of a 2.4-mile swim and a 112-mile bike ride followed by a full marathon (26.2 miles). Being a recreational “ironman” also means waking up in the middle of the night to down an Ensure you keep in a bedside cooler, setting your alarm for 5:30 a.m. to dive into the pool for dozens of laps and hopping onto your bike for three hours after a full day of work.

“I’m always intrigued by what people are really capable of—not just setting a goal, but stretching yourself,” says Saini. “You start off thinking, ‘I’ll never be able to go this distance,’ but then you train and you accomplish it, and it’s like, ‘Wow, what else can I do?’ ”

For Raub, there’s something very Dickinsonian about the process. “There’s a lot that goes into that eight-month training program,” he explains. “In a way, it’s a lot like the Dickinson education. There’s endurance training, strength training, mechanics on the bike, technique in the pool, nutrition and recovery—all these disciplines coming together … and then you reach these goals, and you can see that you’re accomplishing something that never seemed possible before.”

The same is true for Anne Mauney ’04 and Layla Budin ’17, who’ve teamed with other Dickinsonians on Tough Mudders—10- to 12-mile obstacle races that force you to climb walls, wade through ice baths and crawl under exposed wires.

“You literally just push past these obstacles, and at the end you just feel like, if I can do this, I can do anything,” says Budin, who has also climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro, gone bungee jumping and skydiving and completed several sprint-distance triathlons.

That feeling isn’t limited to younger alumni. In addition to Goldberg taking on his first marathon in his 50s, there’s Sarah Nickerson ’91, who started competing in triathlons after having her second child and recently used the confidence she gained from the events to complete a six-month backpacking trip around the world in her 40s.

Or take Beth Sandbower Harbinson ’81, who’s competed in several triathlons a year in her 50s and loves the way the sport’s competitors are becoming increasingly diverse. “One Iron Girl triathlon I went to, there were 2,000 women, every age, every race, every body type—just descending on this park to compete,” she recalls. “I still get goosebumps just thinking about it.”

The most impressive example is Harriette Line Thompson ’45, who—at 94—recently made national news by becoming the oldest person to finish a half-marathon. Just two years ago, the two-time cancer survivor, who runs to raise money for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, became the oldest person to finish a full marathon.

Courtesy of FANNEtasticfood.com. You can read more about Anne Mauney’s experience competing in a Tough Mudder, running the Marine Corps Marathon, hiking Mount St. Helens and more on her food and fitness blog “FANNEtastic Food” at www.fANNEtasticfood.com.

Trend or Cultural Movement

It wasn’t always like this. As recently as the 1960s the sight of an adult running without being chased was so jarring that early participants in this new fitness trend called “jogging” were often stopped and questioned by police. Now there are hundreds of extreme endurance races each year.

As Associate Professor of American Studies Cotten Seiler sees it, the trend is deeply entwined in American culture. Comparing it to the “back-to-nature” movement that emerged in response to the growth of industrialization and assembly lines at the turn of the 20th century, he sees the growth in extreme athletics as part of “a long series of rethinking the body” in response to cultural, political and economic developments.

“It’s sports as a means of individual empowerment—this idea of turning yourself into the most highly developed commodity you can be,” he explains, noting that the increasingly isolated nature of the contemporary life, combined with anxiety over the environment, may be reigniting that back-to-nature impulse as well. “Most of our time is spent behind a computer or cellphone screen, so there’s this impulse to get out into nature in these Tough Mudders and triathlons that give you a chance to connect with these disappearing environments.”

Harbinson would agree. “The world feels more insular to me the older I get, or maybe just as the times change,” she says. “I spend an inordinate amount of time in my workday on the computer or communicating through email or social media rather than face-to-face. This just takes fitness to that next level. I find it so incredibly enriching to participate in something bigger.”

Sunnie Ko ’11, who ran her first triathlon to raise funds for St. Jude Children’s Hospital and is currently training for her first Ironman in September, has a slightly different perspective. “I realize that I’m super lucky and blessed that I can do this,” she says, noting that during training she uses the hashtag #moveforstjude to dedicate each workout to a child too sick to run, swim or bike. “So I feel it’s almost like a responsibility to make the most of what I have.”

Risky Fitness?

Yet experiences like Peeke’s, half blind on a snow-covered mountain, or Sabia’s, running through the dark potentially surrounded by alligators, hint at a darker side to these events. There’s also Raub, who despite completing numerous Ironman races and marathons, was forced out of two events due to severe dehydration and a pulmonary edema brought on by 53-degree waters that nearly forced his organs to shut down. Not to mention the flames, electric shocks and potential falls from great heights Mauney and Budin faced in their Tough Mudders.

“When you’re climbing, you have to make decisions that are life and death,” says Peeke, who has run many half-marathons, gone sky-diving and zip lining and taken on five of the Seven Summits—the tallest mountains on each of the seven continents. “It’s a fine line to dance, but it’s definitely a valuable experience.”

(Full disclosure: Sabia finished her 12-mile leg without encountering any reptilian spectators. Shortly after that half-blind step on Mount Washington, however, Peeke made the call to turn back and live to climb another day.)

DM Photography

Still, many might ask the same question Peeke’s mother asks her—“Is it worth the risk?” For most outsiders, the answer is a simple “no way,” but Professor of Psychology Marie Helweg-Larsen, who studies the psychology of risk, has a more complex answer.

“Our attitude toward risk often has a lot more to do with what we see as normal or necessary,” she says. “Most people don’t worry about the risks of driving because it seems ordinary, but if you look at the number of casualties each year, it’s definitely a risky activity. So from the outside these events might seem more risky because we don’t participate in them, but if you’re part of a community competing in these events, you have a completely different perspective.”

Perhaps that’s why so many of the competitors highlight the communal aspect of what appears on the surface to be highly individualized sports.

“I thought the idea of a Tough Mudder sounded crazy at first,” says Mauney. “Then I saw how much fun my husband had and more of my friends started to get involved, so I thought, ‘Why not embrace the challenge?’”

Budin agrees. “The social aspect is very important,” she says. “You should do it with at least one friend. It’s comforting to go through it with someone you can lean on and encourage—and then celebrate with!”

But perhaps the best answer to the question of whether these sports are worth the risk comes from Goldberg. After leaving his distressed wife to head to the starting line, he finished the New York City Marathon alive and well, the culmination of years of training since Goldberg—an officer in the Army Reserves—discovered he was unable to complete the 2-mile run portion of the reserves’ physical fitness test. Since then, he has completed two other marathons, several 10-milers and the Rock ’n’ Roll Half Marathon, and today, he’s training for a fourth marathon to celebrate an upcoming milestone birthday.

“I’ve had people tell me this is not a wise thing to do,” he says. “But I’ve gotten a lot out of it. To go from literally not being able to run 100 yards to this—it has given me a feeling of accomplishment and confidence, but it’s also a great way to stay physically fit, and that’s the best way to prevent a lot of these diseases and conditions that come with getting older. So when people ask me if this is really a smart thing to do, I say, ‘I really don’t know. Ask me in 30 years, and I’ll let you know.’ ”

Learn more

Published July 7, 2017