Q&A: Not for Shale

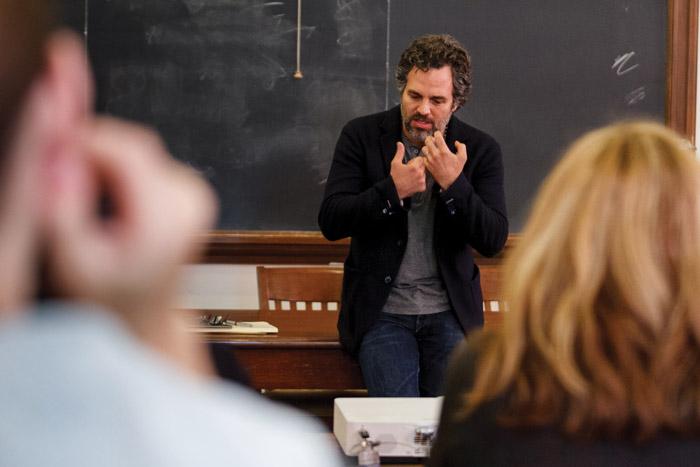

If you've been following Dickinson news this semester, you know that actor and activist Mark Ruffalo was on campus this October as the 2015 recipient of the Sam Rose '58 and Julie Walters Prize at Dickinson College for Global Environmental Activism. Ruffalo's residency included classroom presentations, meetings with student organizations and a public Q-and-A with the Clarke Forum for Contemporary Issues' executive director, Amy Farrell, professor of American studies and women's & gender studies. Here, he discusses what he's passionate about with writer/editor Tony Moore.

Moore: Between the Solutions Project and your anti-fracking work, you’re becoming a real voice in issues involving the energy complex. How did you get so interested in these issues?

Ruffalo: About six years ago, Ramsay Adams, son of John Adams, took me to Dimock, Pa., to show me this new thing, hydrofracking, and how it was affecting people’s lives and communities there, and I saw really desperate people who couldn’t find a place to air their grievances. They just didn’t seem to have a voice, and they basically were asking me to tell the world their story. So I ran home—I wanted to get out of there quickly because that seemed a huge responsibility to me—and I was lying in bed that night, thinking, “OK, Ruffalo, are you really who you say you are? Do you really care about your community? Do you really care about the people around you? Do you believe in justice? Do you think we have responsibility for each other? Or do you just say those things and not act on them, and to what degree are you willing to act on them?”

And I was very fortunate. I have a nice acting career and I also have a voice that happens to reach further maybe than some of those folks, and so that became a place that I saw that I could be useful, and then I just started to study energy. And the question became, “Is there a way to move forward without polluting ourselves and our communities, and has this hundred years of concentrated hydrocarbons taken us to a place now where we can evolve in an energy sense?” And that took me to Stanford University, and I met with Professor Mark Jacobson, who’s the head of the civil engineering department at Stanford. He’d done a white paper saying we could move, hypothetically speaking, the entire United States to 100 percent renewable energy in 50 years if we really put our minds to it based on the technology that we have today. And not only that, but it would create jobs, it would save billions of dollars in remediation and externalities. It would deal with blackouts. Once you have a piece of science that’s been peer-reviewed out of a place like Stanford, the entire conversation shifts. And I said, “Can you do this plan, but for a single state?” And that bloomed into the Solutions Project. Now we have 50 plans for 50 states. This winter, we’ll have plans done for every country in the world to take them to 100 percent renewable energy.

Moore: So technology’s the answer, in a way?

Ruffalo: It’s technology and knowledge, and maybe a simpler life for us, maybe more local-based economies, but really taking it to a much deeper level.

Moore: What do you tell your kids about the environment and your work on behalf of it?

Ruffalo: I’m actually pretty hopeful about things. There are a lot of really wonderful people who are joining in this movement at a moment when the technology is able to take us to another place. There’s a whole awakening of people, and so I share with them what they can understand at 13, 10 and 8. A lot of it, they learn in school. I’m surprised by what they come home to tell me about. I taught them to love their surroundings, and I think that’s a really good place to start.

Moore: Obviously, Dickinson is committed to sustainability and working for the environment, and we’re so happy to have you here. What is it about Dickinson’s mission that made you want to come here for the Rose-Walters Prize and to become part of our community for the residency?

Ruffalo: One of the issues that I really work with and that got me started was water. Most of the data that the environmental side has to rely upon is either industry-produced or produced by the state or colleges, and I see the future of the commons and really the idea of how to protect water in the hands of the communities, in the hands of students of ALLARM. Your ALLARM program here is an amazing start to what could be done all over the United States. I know it’s been here for 30 years, but just in the past five years it started to move out into the rest of the nation, and with novel and newer and easier and cheaper testing technologies, we could start to really create a wall of defense that will deter polluters but also make it easier to catch them when they do it.

Moore: You’re fighting to ensure that fracking stays banned in New York state. Do you see any hope for fracking? Is there a way, on the horizon somewhere, where it could work and it wouldn’t be dangerous?

Ruffalo: I don’t see it. It uses enormous amounts of fresh water in a time when fresh water is becoming more and more precious. Not only does it use it, but it’s very hard to recycle it. Up to 13 million gallons of fresh water are used to frack one well. Out of those millions of gallons, they can only pull up about two-thirds of it. The rest of it has to stay in the ground forever. Out of that water, an enormous portion of that has got to be deep-well injected because it’s coming up with so much contamination that it can’t be put back into the system, so you’re losing fractions of the water table on the planet. You’re running a mass experiment that is completely out of control and without any understanding of where you’re headed in a time when, with global warming, we’re seeing these massive rolling droughts.

Another aspect is, when you drill a well hole, you’re actually creating a pathway between contamination down there and your aquifers, so it isn’t so much that somehow the fracking fluid’s going to work its way up a crack or something; the fracking fluid and the contamination are working their way up into aquifers from the very well that you’re drilling, and these wells are failing. They’re failing at 6 percent by the industry’s own numbers. And they want to drill 55,000 wells in the next 10 years.

You also have the fact that, if we’re going to follow the science of climate change—I can’t even believe I have to qualify that with an “if”—methane is between 30 and 70 times more damaging a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and the amount of methane that we’re losing in transporting fracked gas or extracting fracked gas blows by any benefit that the gas burns twice as clean as any other fossil fuel. All of these issues together make it not only unsafe but would have been incredibly unwise, and right now we have the technology to move past this age-old way of powering our world.

Moore: What alternative energies are you most excited about?

Ruffalo: What’s made alternative energy difficult is the pricing, but what we’ve seen throughout history is that fossil fuels rise at about 12 percent above inflation, and we’re seeing renewable energies dropping every year. We’re at parity right now with wind—it costs the same amount to put a wind turbine out as it does to power your house with natural gas or coal. We’re about three years away from solar being at parity. At some point there’s an inflection point, and then we’re going to pass it. But the energy industry is heavily subsidized by our tax-paying dollars. If we were to pull those tax-paying dollars away, fossil fuels would be a done deal, because renewable energy and the electrification of our transportation system would be so much cheaper.

Moore: As you know, our students are fighting for various environmental causes. What would you say to them about really making their mark in the environmental realm?

Ruffalo: These students are in a very interesting part of the history of mankind, probably not like any other time. You have a way of communicating in a mass, decentralized way, so a lot of information can be passed along to a lot of people without filtration. You also have the specter of climate change, which is existential—probably one of the most existential threats mankind has ever faced. I would say that it’s probably an incredibly exciting time to be alive. It’s a purpose-driven time. It’s a time when our values as human beings can really come into focus, and I would just say be bold. This is a chance to live a really full and exciting life, and what you guys are particularly doing is way out in front of a lot of people, so you’re leaders, and more so than any other generation, you can actually engineer what the future’s going to look like.

Read more of the fall 2015 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Learn more

Published November 13, 2015