Dickinson College Professor Delivers Expert Testimony Before the Maryland General Assembly

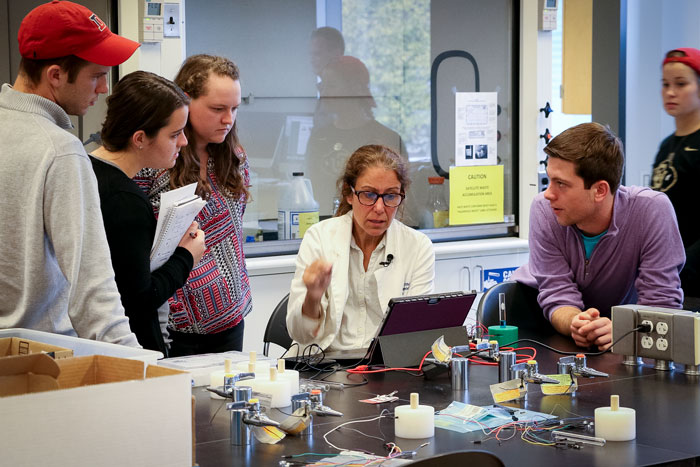

Professor of Chemistry Amy Witter recently brought her expertise out of the classroom and into the Maryland General Assembly. Photo by Joe O'Neill.

With water quality at stake, Professor of Chemistry Amy Witter makes the case for banning coal-tar-based sealants

by Tony Moore

Dickinson College Professor of Chemistry Amy Witter was recently asked by Delegate Vaughn Stewart of Maryland to provide support for HB 0077 in the Maryland General Assembly. The bill aims to end the use of coal-tar-based sealants—which contain toxic chemicals that enter bodies of water through runoff—in Maryland on driveways, parking lots and other asphalt surfaces. On Jan. 20, Witter gave oral arguments, pushing for the passage of the bill.

How did you come to testify about this issue before the Maryland General Assembly?

I’ve published three papers looking at contaminants in sediments from the Conodoguinet Creek and in runoff from coal-tar sealed asphalt surfaces. As a result, I’ve sent these manuscripts to other scientists in the field who work on similar questions as part of the peer review process of science. One scientist, Dr. B.J. Mahler, was initially asked to speak at this hearing, but she suggested me as a replacement.

Why is it so important to you—and to the environment?

In the U.S., we hear a lot about water scarcity, especially in the western U.S. Drought and wildfires are especially strong images in our minds recently. In the East, a different problem exists; we have an abundance of water, but water quality is increasingly threatened as urban areas grow (across the U.S.), and urban stormwater runoff is a major contributor to impaired water quality, affecting both the environment and humans.

It’s critical that we as humans begin to understand that clean water is not a limitless resource. We’ve come to believe that, because water is not priced accordingly. I believe we assume that the supply of clean water will always be there, but there are flaws in that thinking. For one, as climate change proceeds, the water balance is affected. Secondly, the arguments that suggest that we can engineer our way out of water pollution are flawed: The systems that we have in place are simply not designed to filter out or treat the contaminants that are now present in our water supplies. We are all exposed to synthetic chemicals in our water supply that are so problematic that they have been called “forever chemicals.” So, the issue is important to me because coal-tar sealants are another unnecessary source of products applied in the environment that adversely affect the quality of our water.

How did the testimony go? Does it look like the bill banning the coal-tar product will pass?

The testimony reminded me of the need to be very clear in how you present scientific information to the public and of the centrality of chemistry as a way of understanding the world. As a chemist, I see things through a very “chem-centric” lens. But the testimony reminded me that as much as we try to place things into simple categories, there are all these shades of gray that contribute a deeper understanding of how nature actually works. From what I’ve been told, I believe Maryland is closer to passing a bill. Pennsylvania is another story.

Why don’t people just use the less-toxic driveway sealant?

There is an awareness now because consumers are informed of the issues with coal-tar sealants to demand more eco-friendly products. So, the applicators respond. But there is always a lag time between understanding that something is a problem and actually phasing out a product. The process takes time, and it proceeds at different rates around the U.S. My guess is that Pennsylvania will be one of the last states to voluntarily ban coal-tar sealant.

Are other states pushing similar bans? Is it something the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is looking at?

Two states (Washington and Minnesota) and many other municipalities and counties around the U.S. already have bans in place preventing coal-tar sealants from being applied. There is evidence that these bans work. It was a deregulatory environment all around during Trump’s administration, but environmental policy often shifts sharply when a new party is elected. The question of what the EPA will be looking at as we move forward remains to be seen. The Trump administration so gutted the EPA that it may take some time to rebuild.

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published January 22, 2021