Life During Wartime

Singleton Ashenfelter depicts the life of a first-year student/temporary soldier

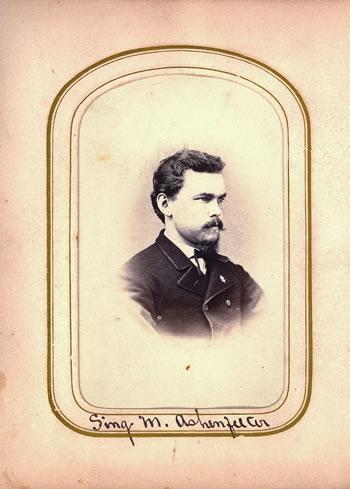

Singleton Ashenfelter, the future U.S. attorney for the territory of New Mexico, as he appeared as a Dickinson student. (Courtesy of Pennypacker Mills, County of Montgomery, Schwenksville, Pa.)

By Jonathan W. White

When Singleton Ashenfelter, class of 1865, entered Dickinson College at age 18 in March 1862, he was very excited by the prospect of living away from home for the first time. But “Sing” also worried about making a good impression and making friends. His correspondence to his childhood friend and future governor of Pennsylvania, Samuel W. Pennypacker, offers a rare glimpse into what life was like at Dickinson during the Civil War.

“I was a stranger to all except [Vosburg] Shaffer,” he wrote to Pennypacker, “and wishing to get into good favor with my fellow students, I adopted the course, which I thought would most readily produce that result. I think I am justifiable in saying that I succeeded in my design.” What was that course of action? It involved late-night pranks, card games during study hours, playing hooky and even serving a brief stint in the Union army.

Ashenfelter and Pennypacker had become close friends growing up outside of Philadelphia, but it took the first-year student four weeks to send Pennypacker a letter from college. Ashenfelter offered his friend “a batch of excuses” for the delay.

First, he pointed out, “I have been so devilish lazy since I have been here.” He had only a little time and energy for writing, so he gave “preference” to “my relatives, [and] female acquaintances.” Second, Ashenfelter explained, “I wished to ‘learn the ropes’ to become acquainted with the ins and outs of College life before I addressed you, in order that I might have material enough to make an interesting letter. Third,—but enough of this; I suppose two will excuse my slowness.”

In his letters, Ashenfelter described college president Herman M. Johnson as a curmudgeonly old killjoy. Johnson had joined the faculty in 1850 as a professor of English literature and been elected college president in 1860. But Ashenfelter was not at all impressed by Rev. Johnson and delighted in playing pranks on the dour man.

Dickinson had a full complement of pranksters in the 19th century. Singleton described an instance to Pennypacker that occurred a few nights after his arrival: “… an attempt was made to squib me.” To accomplish this prank, students first tied their classmates’ door shut with rope, then took a quill pen and filled it “with alternate layers of dry and wet powder.” They would then light the quill, shove it through the keyhole and pound on the door. When the gunpowder exploded it would fill the room with smoke, leaving “such intolerable stench that sleep for the remainder of the night is impossible.”

A group of “squibbers” tied Ashenfelter’s door, stuck a loaded quill through the keyhole and “commenced to pound on the door.” They kept up their ruckus from 11:30 p.m. until midnight.

“Fortunately for my rest the powder did not go off ... [and] having aroused the College, and there being a probability of Doc. Johnson’s appearance, they thought it prudent to beat a retreat,” he wrote.

Ashenfelter quickly became popular among his peers and now found himself on the better end of the jokes. “A few nights afterwards I joined a party of squibbers myself,” he wrote with pride. He and five other students “resolved to initiate” a new arrival from Baltimore. They tied his door shut, filled the quills with gunpowder, “sent the squibs flying through the key hole, and commenced to pound the door with clubs.” They “kept this nuisance up for about ten minutes” and stopped “to take a little rest” when Ashenfelter’s roommate, James Bowman, “was seized by the arm by a Prof. who had stolen upon us unawares. (It was near midnight, and very dark.)”

Bowman jerked his arm and “landed the Prof. on the floor.” The boys then fled “out of the hall” and shut the door behind them so that the professor “could not get out except by a round-about way.” They hastened to their rooms and quickly tucked themselves under their covers. “If a professor had called five minutes after he would have found us all in bed.”

Ashenfelter and his “most intimate College friend,” James Lanius Himes (whom he called “Lan” or “Giglamps”) sometimes found themselves in trouble for their antics. The faculty “accused three of us of plug[g]ing the bellroom and thus interfering with recitations,” he wrote. The boys “pleaded innocent” but to no avail. The college charged them for “the damages done to the bellroom door, and took 400 marks from each of our class standings.”

Aside from pranks and practical jokes, students found other ways to pass the time in an era before television, cell phones and video games. One Saturday morning Ashenfelter and Himes walked 27 miles to visit Himes’ family. “We had a gay time & returned to Carlisle on Tuesday evening.” Back in his room, Ashenfelter was bemused by his roommate’s strange behavior. “My Chum, who, in imagination transformed [himself] into an Eastern juggler, has, for the past half hour, been amusing himself by the exhibition of skillful feats in knife-throwing, to the great detriment of our black-board.”

The war came to Pennsylvania in September 1862 when Confederate Gen. J.E.B. Stuart led a band of cavalry to Chambersburg, Pa., searching for horses and other supplies following the battle of Antietam. In the face of this invasion, many students answered their country’s call.

“Since my arrival here, I have not applied myself to study as strictly as I had expected,” wrote Ashenfelter. “In fact, I dropped College, took up war, and started out as a ‘militia.’ The way of it was this. Heard that Pennsylvania was invaded. Heard, moreover, that she appealed to her patriotic sons for defense. Great excitement in town: everybody patriotic. Caught the prevalent feeling.” Ashenfelter’s terse prose captures the comedy of his military service in the midst of a great national tragedy:

"Thought I had evinced sufficient patriotism, and consequently felt relieved. Took a second thought and came to the conclusion to join the “milishe.” Went down town and fixed my name to the roll. Began to feel enthusiastic. Company fell into ranks, and marched up to the depot amid cheers of the populace. At depot order given “Company rest.” Company rested, (in ranks) for two hours. Began to grow tired of resting. Three hours. Mutiny began to be visible. Men straggling out of ranks. Recalled to duty by the whistle of the cars, which soon came to hand. Jumped aboard. Train started amid a profusion of cheers and tears. Arrived at Chambersburg, very cold. Waited about a half hour. Finally ordered to “Forward march.” Marched three miles. Came to a woods and halted. Discovered that it was midnight and began to feel sleepy. Marched into the woods. Built fires and fixed up as comfortably as possible. Tried to sleep, too much noise. Tried again; another failure. Gave it up in despair and lay on my back, “star gazing” until day light. Rose up half frozen. Went up to the fire and warmed myself. Breakfast time. No rations had arrived. Forced to “chew the cud of sweet and bitter fancy” or starve. Chose the former and got the blues like thunder. Dinner time. Beef and bread just arrived. Took double rations, and consequently there was none left for supper. Went to work and built tents, from rails and straw."

Discovered that it was Sunday, and the discovery occasioned us no little surprise. Went to bunk. Woke up next morning in fine spirits, but d—d cold. Plenty of grub. Spent four days in camp. Began to get used to it. Never liked anything better in my life. Woke up one morning and found myself discharged. The reason was as follows. About twenty students were in. Scotch afraid College would break up. Petitioned Gov. [Andrew] Curtin [class of 1837] for our discharge. Gov. ordered it, and our militia service was over.

Military service was not the only excitement for Dickinson students during the war. The college’s Commencement each spring provided another sort. Each of the school’s literary societies elected six orators to represent them at the ceremony. The free flow of alcohol surrounding these elections inevitably led to “any quantity of drunken students” rollicking throughout campus.

Amazingly, Ashenfelter had “sufficient moral courage to refrain from drinking … & consequently [had] the pleasure of addressing you this evening.” Still, he relished relating these stories of college life to his friend back home. “As you are a young man of steady habits,” Ashenfelter wrote dryly to Pennypacker, “I have no doubt that you would be exceedingly horrified if you were within the precincts of Dickinson College tonight. One who has never been in the habit of associating with ‘sportive’ youths cannot possibly imagine the din which is raised by a party of students ‘on a tight.’ ”

Ultimately, the young men at Dickinson were here for an education. Their antics aside, they did an inordinate amount of reading. Singleton boasted that the libraries at Dickinson contained “in all about 25,000 volumes, and there is therefore no difficulty whatever in always having interesting matter on hand.”

Ashenfelter regularly listed the books and authors he was reading—in all manner of modern and classical languages—as a first-year student. These included works by Ovid, Homer, Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens; histories of Egypt and Carthage; the Koran and the Bible, among many others. Remarkably, he considered himself “lazy.” And like college students of all eras, he sometimes became “so bored with reading & study” that he wished he had more correspondence from home.

More than 40 letters survive from “Sing” to “Pennie” during these college years, and the two men remained correspondents for the rest of their lives. In 1867, Ashenfelter traveled around Cape Horn and settled in Valparaiso, Chile. He returned to the United States in 1868 to study law; two years later, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him U.S. attorney for the territory of New Mexico. He died in 1906. At the time of his death, Ashenfelter’s childhood friend, Samuel W. Pennypacker, was serving as the 23rd governor of Pennsylvania. Their correspondence is preserved among the governor’s private papers at Pennypacker Mills, a historic site in Schwenksville, Pa., in Montgomery County.

Jonathan W. White is assistant professor of American studies at Christopher Newport University and author of Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (2011).

Published April 3, 2012