Tangible Artifacts

Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

Harlem Renaissance/New Negro collection grows in the Dickinson archives

by Tony Moore

Recent additions to Dickinson's Harlem Renaissance collection are helping students gain a better sense of this significant movement in American literature. Armed with the expanded collection, students in Professor of English Claire Seiler's Celtic Revival/Harlem Renaissance course are learning exactly how this movement evolved during a pivotal time in the country's history.

“What I wanted to do was look at how the Harlem Renaissance, or the New Negro movement, as it was more often called, took shape—and took shape in print,” Seiler says, noting that the movement involved visual art, musical theatre and music as well as heavy doses of literature and social commentary.

From Wish List to Syllabus

To do that, Seiler worked with College Archivist Jim Gerencser ’93 and Special Collections Librarian Malinda Triller Doran to expand the collection.

“They invited me to put together a wish list of Harlem Renaissance materials, and Jim and Malinda were able to find everything,” she says, noting that Gerencser and Triller Doran have been major assets in collecting and facilitating the use of these materials collegewide. “It was pretty much every scholar-teacher’s dream.”

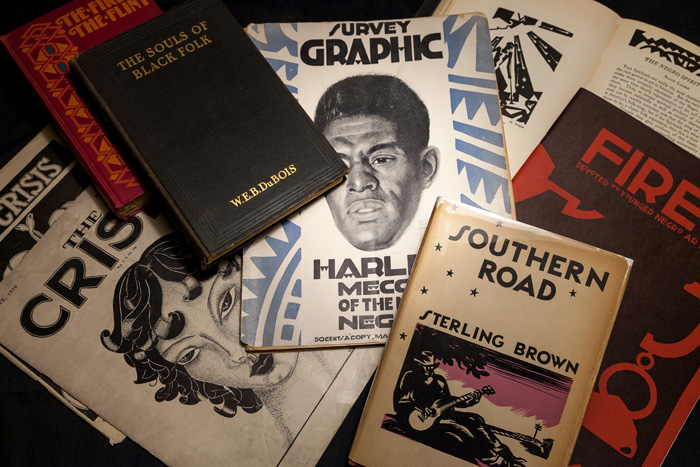

In this case, “everything” includes archival material pertaining to the Harlem Renaissance/New Negro Movement of the 1920s and 30s, such as rare periodicals, first editions of monographs and anthologies by African American writers and intellectuals like Alain Locke and James Weldon Johnson. Also acquired were first editions of volumes by Langston Hughes and Jesse Redmon Fauset as well as a first edition of W.E.B. Du Bois’ landmark book Souls of Black Folk (1903), which Seiler says is “one of the books that invents what we think of as American modernity.”

The haul was so impressive, in fact, that it reshaped Seiler's course. “The collection animates the movement for students, so I overhauled my whole syllabus to prioritize print culture and material history,” she explains.

Letters to the editor

A major facet of the print culture and material history that Seiler wanted to capture for students was a collection of The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP, of which Du Bois was the editor. The library now has 15 print copies, and Seiler had her students read through them and pen a letter to Du Bois, in which they discussed a topic addressed in an issue.

“Being able to read and handle archival material that spoke about the failures of the Constitution allowed me to invoke what I have learned in both the Policy Studies Department and the English Department in a close reading analysis,” says Michaela Zanis ’19 (law & policy, English), who explored how the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments should have better protected the African American community.

“After completing this assignment, I felt very attached to my particular issues of The Crisis,” says Phoebe Serlemitsos ’20 (English), whose letter focused on anti-lynching laws and nongovernmental anti-lynching movements. “As I researched, I became more and more interested in this topic, [and] I would say that my interest stemmed from my repeated access to the original copy of The Crisis issue. I felt that since I had the tangible artifact I was more connected to the assignment.”

Serlemitsos also found an unexpected Dickinson connection in the material as well, when the class had a discussion about Esther Popel Shaw, Dickinson’s first known black female graduate (1919), whose poem “Flag Salute” was featured on the November 1940 cover of The Crisis.

In our time, in their time

Seiler also recently shared the materials with Dickinson alumni during a presentation at Homecoming & Family Weekend.

“Alumni and families said they had no idea the college had this collection,” she says. “They were so glad to hear that we were investing in these materials and teaching with them, and parents were amazed at the objects their kids get to work with in their classes.”

Those objects also include books of African American poetry, pamphlets and important novels such as Nella Larsen's Quicksand, George Schuyler's Black No More and Zora Neale Hurston's first novel, Jonah's Gourd Vine.

“This archive puts these books back in their time,” Seiler says. “That doesn’t let us release everything that has happened since or what we know now, but it compels students to confront literary work as it appeared, before it was canonized or forgotten. Seeing the Harlem Renaissance unfold in print means students have to make their own sense of this incredibly dynamic movement. And you can tell that means a lot to them—especially to see how younger writers, writers not much older than they are, challenged not only the U.S. racial political regime but the orthodoxies of the New Negro movement.”

The expansion of the college's Harlem Renaissance collection was funded by the Goodyear Endowment, which was established by Mary Goodyear ’28. Recently, this endowment also enabled Dickinson to acquire such items as a first edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1668) and early editions of Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published November 30, 2017