‘Question everything’

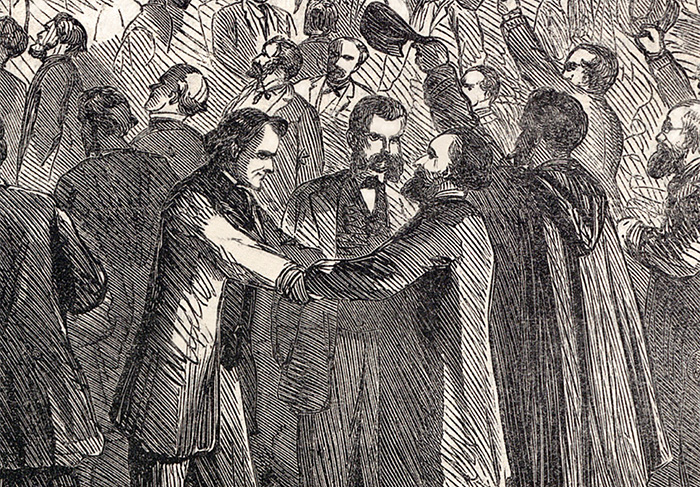

Detail from the cover of Harper's Weekly Magazine (Feb. 18, 1865), depicting the final passage of the 13th Amendment. Shaking hands are (left to right): Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley and John A.J. Creswell.

Dickinsonians team up to bring Civil War figure into the spotlight in new e-book

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

It began with two lowly letters—“A” and “J”—and mushroomed into an absorbing biography of a John A.J. Creswell, class of 1848, a confidant of Abraham Lincoln and impassioned abolitionist who might still be forgotten, but for those two contested initials.

A new e-book, Forgotten Abolitionist: John A.J. Creswell of Maryland, brings that orator and statesman to life, nearly 170 years after he graduated from Dickinson, where the seeds of his legacy were planted. Written by Professor Emeritus of History John Osborne and Christine Bombaro ’93, associate director for research & instructional services at Dickinson, it is available for free download through smashwords.com.

Funded by a grant from the Digital Humanities Advisory Committee, Forgotten Abolitionist is the first e-book published by the House Divided Project, and it kicks off a series of short biographies on overlooked figures in Civil War-era America. It traces its roots back to 2006 when Osborne, a House Divided co-founder, asked Bombaro to help guide students in his Intro to Historical Methodology course as they researched the lives of 19th-century alumni.

To prepare, Bombaro requested an assignment of her own—so she could have a comparable research experience, with Dickinson’s Archives & Special Collections as a starting point—and Osborne pointed her to Creswell, unknowingly sparking a more in-depth investigation.

Video by Joe O'Neill

Andrew, Angel, Angle?

Little had been written about Creswell, save for a 1968 article about the U.S. Postal Service, which mentioned his service as postmaster general. As Bombaro dug in, she noticed something peculiar: In his Dickinson matriculation and graduation records, Creswell’s two middle names were “Andrew Jackson,” but in some other documents, including at the Library of Congress, he was “Angel James.” Was it an error, or had Creswell opted for a bizarre name change at some point, as Library of Congress staff contended?

Bombaro put the mystery aside after the class was finished, but she was reminded of it each time she was asked to lead a new group of Historical Methodology students. When she needed a case study for a book on research methodology, she secured funding from a Dana Research assistantship and tasked John Monopoli ’11, then a psychology major at Dickinson, with uncovering the facts.

It wasn’t easy, since there is no formal collection of Creswell’s papers, and the signatures that survive list only middle initials. In addition to the “Andrew Jackson” discrepancy, there were references to “Angle James” (most likely a printing error), and to “John A. J. Cresswell,” “Col. Creswell,” “General Creswell” and others.

Despite excellent scholarship, Monopoli couldn’t confirm or deny Bombaro’s theory that the Library of Congress listing was erroneous, but he did uncover clues that the forgotten alumnus had a far bigger role in American Civil War history than previously known. Bombaro’s curiosity spiked, and a joint research project with Osborne began.

Over three years, they learned that the forgotten Creswell was a confidante of Abraham Lincoln; a riveting orator who shared the stage with Frederick Douglass; a congressman, credited with keeping his home state, Maryland, in the Union; a senator; and a U.S. Supreme Court nominee. He was also a revolutionary public servant who helped modernize and integrate the U.S. Postal Service by appointing African Americans to top positions (much to the consternation of many in the South). He also worked on a committee that gave war reparations to the U.S. from Britain, which had supported the South during the war.

“The more we learned, the more we realized that he deserved to be dug out of history,” Bombaro says.

The seeds of his metamorphosis

Bombaro and Osborne originally planned to perform that excavation in a journal article, but they soon realized that they’d need to cut out a lot of research to do so. By publishing through House Divided, now in its 10th-anniversary year, they were able to expand the material into a full-length study. The result is a gripping study of a public figure caught between Northern and Southern ideals, who transformed his views over time.

In it, the authors explore that slow metamorphosis throughout Creswell’s life, from Southern schoolboy to conservative businessman to noted Republican leader and abolitionist, as well as his identity as a Dickinson valedictorian and, later, trustee. They argue that the seeds of Creswell’s ideological conversion were sown during his undergraduate years, when he connected with future peers in the federal government and experienced firsthand the 1847 McClintock Slave Riot in Carlisle.

As to Creswell’s middle names, the authors uncovered evidence that his name remained the same from birth through death, and that the Library of Congress listing is incorrect. (The error may have originated from the Library of Congress, Bombaro suggests, but while the institution’s staff agree that the evidence is compelling, they have not changed their records to date.)

Nine years after the adventure began, Bombaro uses the Creswell story in historical methodology courses as a prime example of the exacting nature of research and the rewards it can bring.

“I think students have this idea that history has already been written and everything’s been said before, but you never know where an initial question is going to lead you,” she says. “You also have to question everything. The authoritative sources are not always right.”

Learn more

Published November 10, 2015