Beetle Juice

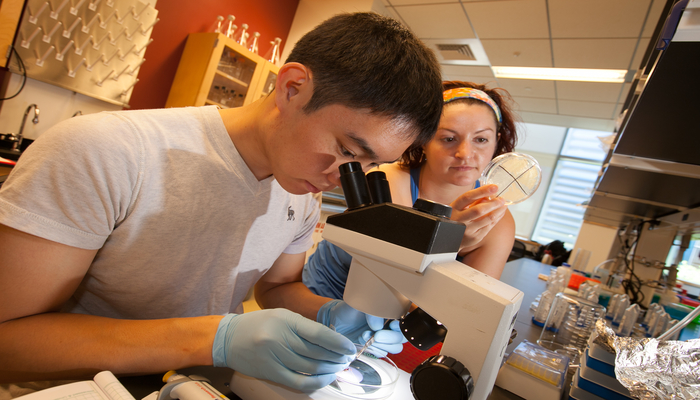

Assistant Professor of Biology Dana Wohlbach examines a plate with a yeast culture while Youki Sato '16 dissects a beetle at a microscope.

Probing the future of biofuels and evolution of symbiosis in beetle guts

by Ben West '14

The rain has just stopped; conditions are now ideal for a beetle-collecting expedition. Crawling beneath a veneer of wet leaves or hiding inside a decomposing log at Reineman Wildlife Sanctuary, the beetles themselves are not actually the targets of the nimble hunters—armed with small wooden axes and dozens of glass vials—who now pursue them.

The beetles are but vessels for undescribed communities and undiscovered species of fungi dwelling in their guts. Probing the DNA of these yeasts is the summer research project of chemistry major Youki Sato ’16 and Assistant Professor of Biology Dana Wohlbach. Their results may impact the efficiency of biofuel production, clarify the ecology of these tiny ecosystems and help explain the evolution of symbiosis itself.

“We’re interested in understanding the relationship both from the standpoint of the beetles and from a fungal diversity standpoint,” says Wohlbach. “What is the benefit to the beetles of having yeast and other microorganisms in their gut, and what is the benefit to the yeast of living in a beetle gut?”

Once apprehended, the beetles are dissected, their guts plated, the yeasts cultured, the DNA isolated and sequenced. The yeasts can break down the sugars locked in the woody plant material the beetles eat, aiding their digestion. Understanding the yeasts' knack for breaking down hard-to-reach sugars could come in handy in processing biofuel, which is increasingly made from grasses, corn stalks and cobs.

As Sato points out, “this family of yeasts has been used before” to digest sugars from those sources. “There might be a possibility of using these new strains in improving [production] processes.”

Sato and Wohlbach are most excited to use the DNA sequencing to deepen our understanding of how symbiotic relationships form. “We can begin to explain the nature of symbiosis, understanding how two organisms cooperate and inhabit the same environment,” Wohlbach says.

The lab in the Rector Science Complex exhibits its own form of symbiosis. Sato, sitting at the bench, stares into a microscope while wielding a pipette. Wohlbach opens a drawer and flips through growth plates, releasing an aroma of bread, beer and mold. Though the smells are confined to the lab, similar student-faculty research partnerships can be found all across campus this summer, and the results contribute as much to learning as they do to science.

“It’s a great opportunity from a students’ perspective just to learn and really have input in a scientific project, not just to be told what you’re doing,” says Wohlbach, herself a product of undergraduate research in a liberal-arts setting. “He gets to see what it’s really like to be a scientist as opposed to just doing a project in the classroom. This is eight hours a day, real research.”

Sato, for his part, plans on a career in medicine. After classes with Wohlbach, he wanted the opportunity to do research with her. He doesn't admit it, but he has brought more than just his chemistry experience to this partnership.

“He was definitely less scared about collecting beetles than I was, and I appreciated that. So I think there were a lot of benefits on both ends.”

Learn More

- Research at Dickinson

- Department of Chemistry

- Department of Biology

- Reineman Wildlife Sanctuary

- Latest News

Published July 31, 2014