The Unrevised Life

by Ted Merwin

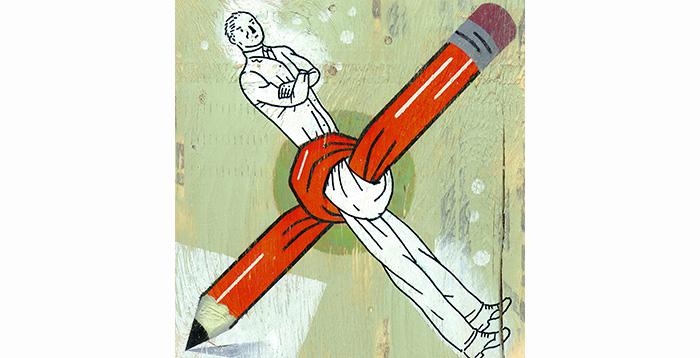

My dad wasn’t physically violent, but give him a red pencil and a piece of someone else’s writing, and his bushy black brows would beetle, his eyes would narrow and his breathing would get heavier. His pencil would dance with shivery cross-out lines crowned with loops and swirls, bizarre abbreviations and biting sarcastic comments in the margin. I learned never to show him my high-school papers, lest the editing session end in tears. It was as if that red pencil had drawn blood.

Three decades later, I’m a college professor, and I find myself often having to give students the unwelcome news that their essays are not exactly stellar. When they read my comments, I recognize the look of shock and dismay on their faces, of pain and betrayal — perhaps even fear. They seem to be going through one of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’ stages in coping with the death of a loved one — denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

“Why do I have to keep rewriting this paper over and over?” one of them moaned to me recently. “You can’t teach me to write in the course of a single semester. Why can’t you just reward me for the work that I’m doing?”

That same afternoon, I received the peer reviewers’ reports on a manuscript that I had spent more than a decade revising and resubmitting to one agent, editor and publication house after another. And now, when I thought it was finally finished, here was bad news all over again — my thesis wasn’t well-supported, I was given to sweeping generalizations, I brought in too many anecdotes and I went off on too many tangents. My work wasn’t worthy, one of the reviewers said, of publication by such a prestigious press. I blinked back tears. I had new empathy for the students who accused me of bursting their bubbles.

High-school or undergraduate papers are not on the same level as a book manuscript by a successful, published writer. But negative feedback on one’s writing is difficult for anyone to absorb. We have put our -insecurities and vulnerabilities on display, and they have been torpedoed. We feel demoralized, distressed — perhaps even devastated. We perceive the yawning gap between the image that we have of ourselves and the ways in which others perceive us.

But no one gets it right on the first try. The Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov once confessed that he had “rewritten—often several times—every word I have ever published. My pencils -outlast their erasers.” Or, as the British poet Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch famously exhorted, “Murder your darlings.”

In fact, all of life is a massive, often painful rewriting project; we spend our lives constantly revising our own history, arriving at new understandings and perspectives on our past as we age. We learn things that we plaintively, intensely wish that we could tell our earlier selves about how things would work out. Most of us gain some wisdom and self-knowledge in the process; an unrevised life, to paraphrase Socrates, is not worth living.

Students may not like to hear it, but the most important part of the writing process is the rewriting, the chasing down of those stray thoughts and elusive ideas, the forging of new connections, the focusing, clarifying, streamlining and shaping. It reminds me of planting seeds and then, when they germinate, giving them a structure to lean on, a framework that will keep them from expanding chaotically in all directions. (This is why we talk about “pruning” our prose, as if it were an unruly shrub or vine.) Or like making furniture by planing wood, cutting grooves and making dovetail joists — all so that the finished piece hangs together in a unified and elegant way.

When you revise, you see things that you missed the first time, things that teach you about the workings of your own mind and that amaze you with your own insight. You discover your ability to strike words together like flint and stone, creating silvery sparks and illuminating a topic in a way that no one has ever done before. And you understand why you subjected yourself to that bruising assault on your ego: It was for this ecstatic moment of finally getting your writing exactly, exquisitely and incontrovertibly right.

Published October 28, 2013