Hands of Time

By Tony Moore

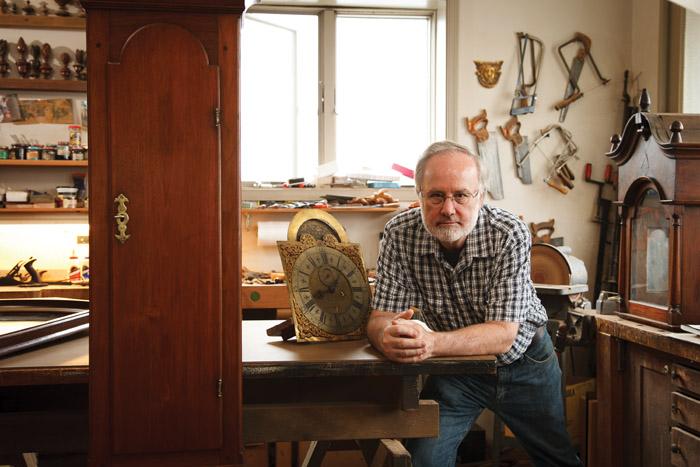

Walking into David Bowers ’71’s house is a little like walking into Jane Eyre’s Thornfield Hall. Richly wooded furniture is everywhere, and the ticking of grandfather clocks is the only sound breaking the meditative quiet that fills the air.

This is what happens when you make your living restoring furniture and clocks, and when you’re really good at it. “I grew up with this,” Bowers says. “My father pretty much did this all his life. So I did it weekends and summers as I was growing up.”

Becoming a part of the family business wasn’t part of his plan, though, as Bowers started out at Dickinson in the late 1960s as a pre-med student and graduated with a philosophy degree. “I didn’t really consider what I wanted to do as a career,” he recalls. “It was the summer of love, the hippie generation, so I didn’t think in those terms.” After graduating from Dickinson, Bowers headed to Boston College to study for a Ph.D. in philosophy.

“I was headed toward a teaching career,” he says, noting that he taught introduction to philosophy courses as a teaching fellow for two years. “But I just decided that I didn’t like it that much.” Like all things that were meant to be, the restoration business was with Bowers all along, just waiting for him to be ready for it. “So I went back to work with my father, and I fell right back into it,” he says. “That was 1975.”

Bowers, who is married to Brooke Wiley, a studio technician in Dickinson’s art & art history department, is still at it 38 years later, but now he knows his work as well as his own face in the mirror.

“Usually I’ll know the period right away when someone brings a piece in,” Bowers says. “But sometimes I have to make an educated guess and then do some digging.” The digging process has led to some interesting discoveries over the years, such as the time a tall clock came into his shop for restoration and turned out to have a twin.

“I was just looking through a book for the clock, and there it was,” he says. “There were only two, and they were virtually identical. So it was a matter of finding the mate to this clock,” which he knew must be out there somewhere. That somewhere was a museum at Yale University, 270 miles east. The museum sent Bowers digital images so he could correctly recreate the missing elements, and after Bowers restored the clock, it later found its way to the Biggs Museum of American Art in Dover, Del.

“I don’t think I would have stuck with it if I weren’t so darn good at it,” he says. “There’s a certain satisfaction to it, and that’s a big part of it— the reward of doing a job well.”

He looks around the room, filled with his life’s work, and the discussion turns to defining his work and in turn how it defines him.

“What I do is an art, but I tend to think of it more as a craft,” he says. “So there’s that distinction of how much art there is and how much craft there is. I wouldn’t say I’m an artist. I’m an artisan.”

Published October 28, 2013