Bronze or Bust

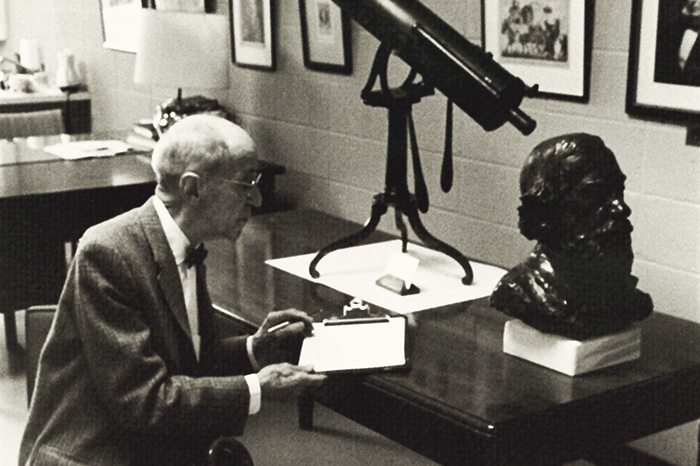

Don Sailer, library digital projects manager, with Dickinson’s bronze bust of Moncure Conway, class of 1849. Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

by Grace McCrocklin ’16

It’s not often that an ordained minister confesses to pulling “the greatest prank perpetrated at Dickinson.” It’s even more unusual for that minister to have matriculated at Dickinson at age 15 and go on to become a preeminent abolitionist, suffragist and humanist freethinker. But like his close friend Walt Whitman, Moncure Conway, class of 1849, contained multitudes. More recently, he’s also at the center of an international hunt for a missing bronze bust.

Conway, son of a wealthy Virginia slaveholding landowner, was profoundly influenced by Dickinson professors and abolitionists Spencer Fullerton Baird, class of 1840, and John McClintock, who led the McClintock Riot of 1847 in an effort to enforce a new Pennsylvania law that contravened the Fugitive Slave Act.

But Dickinson also set him on his path as a writer and serious thinker. After he graduated, Conway served briefly as a Methodist minister, attended Harvard Divinity School (where he became a protégé of Ralph Waldo Emerson and joined the Unitarian Church) and spoke at abolitionist events throughout the country. In 1863, he traveled to London to convince a divided Britain to back the Union cause. Conway faltered diplomatically, however, when he precipitously offered to the Confederate representative in Britain an end to the war in exchange for full emancipation. Rebuffed, he took a position at the South Place Religious Society in London, which turned out to be exactly the tonic he needed: He stayed there for most of his professional life, lecturing, traveling and publishing some of his most important work.

Conway was not always a moral compass, however. His prank on President Jesse Truesdale Peck, who was briefly detained by orderlies of a Staunton, Va., insane asylum based on a letter Conway had sent to the institution, has become the stuff of Dickinson legend. Conway kept his involvement a secret for decades, confessing to the practical joke in an 1875 letter to The Dickinsonian, noting it as “the very essence of college mischief.”

Boyd Lee Spahr, class of 1900, with Joseph Priestley’s telescope and the Conway bust, 1967.

Conway’s friendships thrived in the United States as well. He was well known in literary circles, serving as literary agent in London for Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and Louisa May Alcott. A prolific author, Conway published across genres, including an authoritative biography of Thomas Paine, a two-volume autobiography, travel literature, as well as studies of Hinduism, transcendentalism and demonology. He died in November 1907, just six months after delivering an address at Dickinson celebrating the 225th anniversary of William Penn’s Frame of Government of Pennsylvania and advocating for an academic department of “peace and public service.”

Fast forward to 2015, when the renamed Conway Hall Ethical Society began digitizing its monthly newsletters. In the process, archivists discovered a 1905 report detailing the process of fundraising to purchase a bronze bust of Conway. A 1927 photo confirmed that a bust had once existed but had since gone missing.

A Google search led Conway Hall investigators to Dickinson’s Archives & Special Collections. “We got in contact with Don Sailer [library digital projects manager],” said Jim Walsh, CEO of Conway Hall. “We found out that Dickinson had a bust, started to understand what was going on and then thought, ‘Well, this is really annoying that we don’t have ours. What can we do?”

He continues, “One of the largest 3-D printers in the world is just down the road from us, about half a mile away. We had a look in there and spoke to them about the bust. By that time we understood how large it was, because Dickinson had given us the measurements.” The printer had recently completed a job for a sculptor in which it had fabricated a similarly sized bust in plastic with a 2-millimenter coating of bronze.

“It looked fantastic,” Walsh says. “At that point, it became obvious.”

Walsh’s conversations led to the decision to film a documentary about Conway, hiring a presenter and camera operator to travel through Pennsylvania and New York, stopping at locations important to Conway’s life. The crew was on campus this spring, shooting footage of Memorial Hall and of the eponymous residence hall in the Quads neighborhood.

Conway, circa 1906.

They also spent time talking with Sailer and with College Archivist Jim Gerencser ’93 and taking photos of Dickinson’s bust, from all angles. Their work is continuing through the summer. Walsh plans to open a café at the society’s central London location this fall, with a ceremony to unveil the restaurant, the documentary and the new bronze bust. With help from Dickinson, Walsh says, “We can use technology to save our heritage and get our bust back to Conway Hall.”

Learn more

Published July 12, 2016