Dr. Benjamin Rush founded Dickinson with a unique vision of the liberal arts in mind. Rush’s Dickinson was not to be a place of removed contemplation but of active engagement with the wider world. Today, Dickinson students utilize the timeless rigors of liberal learning to confront the most critical challenges of our globalized age, with the College’s research and study centers abroad functioning as living laboratories. This section highlights recent student research projects. What will you do abroad . . . ?

A Year in South America, Two Global Research Projects

AJ Wildey, Dickinson '13

Traditional Farming Beliefs and Practices in an Age of Big “Ag”:

In Peru, A Surprising Mixing of Tradition and Technology in Agrarian Communities  Last fall, in Coporaque, Peru, a rural farming community, I researched changes in traditional beliefs and farming practices brought on by global economic imperatives and the corporatization of agriculture. I explored, for instance, how traditional tenets of Andean culture responded to or retained relevance in the contemporary agrarian context. The character of “Pachamama” (Mother Earth) plays a particularly prominent role in the oral traditions of rural farming communities, where agrarians depend on healthy crops for their livelihoods. Traditionally, after seeds are sown agrarians assemble a small sacrifice to "Pachamama" to apologize for cutting into Her with their plows and ask for Her help in strengthening the seeds to produce a bountiful harvest. The sacrifice is then typically set ablaze and left to burn its course. But how do the modern influences of globalization affect traditional beliefs, such as the historically close relationship between farmer and Pachamama? With the importance of crop cultivation defined increasingly in strictly economic terms, do traditional beliefs and relationships break down? Are the crops cultivated by rural agrarians becoming a means to solely economic ends? Or are traditional beliefs and indigenous connections to nature maintained, even if altered by new economic realities? Likewise, the traditional practice of “ayni” (reciprocity) encourages community efforts, especially when working in the fields. But, in a parallel way, does contemporary societal emphasis on individual efforts render ayni obsolete? These questions formed the core of my inquiry. And my time abroad provided me with direct, first-hand accounts of the effects of global integrations on these traditional beliefs and practices. I lived with a family that owned seven small fields. I accompanied them in the fields on their daily work. And, additionally, I developed and administered among a broad group of community members a survey designed to gather data on current perspectives on traditional practices and community relationships. I also conducted numerous direct interviews with various agrarians, including the mayor of Coporaque, to learn about plans for future agricultural initiatives. What I learned through survey data and direct observation surprised me: Though some traditions have fallen into disuse, the majority have been retained and continue to be held up as vital components of contemporary agricultural success. While the practice of ayni, for instance, is not as widespread as it once was, it is still viewed as special and relevant, and certain initiatives enabled by modern technology, such as the construction of a high-capacity canal in the face of water shortages, have, in fact, strengthened relations in traditional communities, and in some ways reinforced traditional beliefs. My investigation in Coporaque is far from complete—it is research that I plan to continue in graduate school. But even in this preliminary stage, it presents a tantalizing glimpse of some of the ways in which rural communities adapt to globalizing forces, incorporating the modern while maintaining the past.

Last fall, in Coporaque, Peru, a rural farming community, I researched changes in traditional beliefs and farming practices brought on by global economic imperatives and the corporatization of agriculture. I explored, for instance, how traditional tenets of Andean culture responded to or retained relevance in the contemporary agrarian context. The character of “Pachamama” (Mother Earth) plays a particularly prominent role in the oral traditions of rural farming communities, where agrarians depend on healthy crops for their livelihoods. Traditionally, after seeds are sown agrarians assemble a small sacrifice to "Pachamama" to apologize for cutting into Her with their plows and ask for Her help in strengthening the seeds to produce a bountiful harvest. The sacrifice is then typically set ablaze and left to burn its course. But how do the modern influences of globalization affect traditional beliefs, such as the historically close relationship between farmer and Pachamama? With the importance of crop cultivation defined increasingly in strictly economic terms, do traditional beliefs and relationships break down? Are the crops cultivated by rural agrarians becoming a means to solely economic ends? Or are traditional beliefs and indigenous connections to nature maintained, even if altered by new economic realities? Likewise, the traditional practice of “ayni” (reciprocity) encourages community efforts, especially when working in the fields. But, in a parallel way, does contemporary societal emphasis on individual efforts render ayni obsolete? These questions formed the core of my inquiry. And my time abroad provided me with direct, first-hand accounts of the effects of global integrations on these traditional beliefs and practices. I lived with a family that owned seven small fields. I accompanied them in the fields on their daily work. And, additionally, I developed and administered among a broad group of community members a survey designed to gather data on current perspectives on traditional practices and community relationships. I also conducted numerous direct interviews with various agrarians, including the mayor of Coporaque, to learn about plans for future agricultural initiatives. What I learned through survey data and direct observation surprised me: Though some traditions have fallen into disuse, the majority have been retained and continue to be held up as vital components of contemporary agricultural success. While the practice of ayni, for instance, is not as widespread as it once was, it is still viewed as special and relevant, and certain initiatives enabled by modern technology, such as the construction of a high-capacity canal in the face of water shortages, have, in fact, strengthened relations in traditional communities, and in some ways reinforced traditional beliefs. My investigation in Coporaque is far from complete—it is research that I plan to continue in graduate school. But even in this preliminary stage, it presents a tantalizing glimpse of some of the ways in which rural communities adapt to globalizing forces, incorporating the modern while maintaining the past.

Successes and Shortcomings of Intercultural Education in Bolivia:

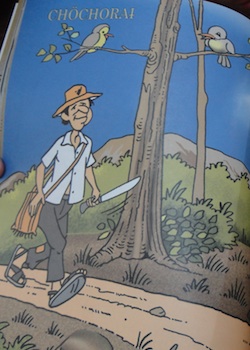

A National Initiative in the Most Diverse Nation in South America In the spring, I investigated whether newly proposed educational reforms in Bolivia truly and equitably incorporate each of Bolivia’s distinct cultural groups in the national effort to establish an intercultural curriculum. This is a daunting task: With at least 36 different indigenous groups, Bolivia is the country in South America with the largest indigenous population. Current tensions stem from the wide-spread perception among many members of Eastern Amazonian groups that the educational initiatives of the present government—led by Evo Morales, who is Aymara, a Western Andean group—unfairly favor Western Andean cultures over Eastern Amazonian cultures. The Law of Avelino Siñani and Elizardo Pérez, slated to take effect in the 2012-2013 school year, is the latest in a long series of educational reforms. My research revealed that, despite its laudable intentions, it, too, fails to represent adequately the contributions and traditions of Amazonian cultures. What would a truly intercultural curriculum in Bolivia look like? This is question as complex as the ethnographic makeup of the country itself. As part of my investigation, I visited the headquarters of Teko-Guaraní, an NGO that sponsors intercultural education initiatives in the Amazon among the Guaraní, a well-known Amazonian group. There, three of the main instructors explained that the success they have achieved in helping their students incorporate modern aspects of society with traditional practices could be brought to a national scale if those designing the new curriculum would take into account Teko-Guaraní’s guiding principle: Considering first the needs of the community. Bolivia cannot afford to overlook the vast cultural diversity of its citizens in favor of composing a curriculum that represents only one group. Truly encouraging children to respect and take an interest in different cultures comes through opening oneself up to new ideas, faculty at Teko-Guarani argued. Though I am by no means an expert in educational reform, my research led me to participate in a special initiative: “Kids’ Books Bolivia,” a project that provides students the opportunity to write, illustrate, and publish children’s books that promote multicultural understanding and tolerance. While "Kids’ Books” was founded in the country’s Andean region, I choose to make my book about an Amazonian topic. Based on my research, I felt it was important to make a special effort to emphasize the significance of the (sometimes underrepresented) Amazonian cultures. (Even among the several dozen books that previous students have published working with the project, notably only a handful have covered Amazonian topics.) The book on which I worked takes the traditional Guaraní legend of the chöcho, a bird believed to have the power of augury, and reintroduces it to a wider audience in three languages: English, Spanish, and Guaraní.

In the spring, I investigated whether newly proposed educational reforms in Bolivia truly and equitably incorporate each of Bolivia’s distinct cultural groups in the national effort to establish an intercultural curriculum. This is a daunting task: With at least 36 different indigenous groups, Bolivia is the country in South America with the largest indigenous population. Current tensions stem from the wide-spread perception among many members of Eastern Amazonian groups that the educational initiatives of the present government—led by Evo Morales, who is Aymara, a Western Andean group—unfairly favor Western Andean cultures over Eastern Amazonian cultures. The Law of Avelino Siñani and Elizardo Pérez, slated to take effect in the 2012-2013 school year, is the latest in a long series of educational reforms. My research revealed that, despite its laudable intentions, it, too, fails to represent adequately the contributions and traditions of Amazonian cultures. What would a truly intercultural curriculum in Bolivia look like? This is question as complex as the ethnographic makeup of the country itself. As part of my investigation, I visited the headquarters of Teko-Guaraní, an NGO that sponsors intercultural education initiatives in the Amazon among the Guaraní, a well-known Amazonian group. There, three of the main instructors explained that the success they have achieved in helping their students incorporate modern aspects of society with traditional practices could be brought to a national scale if those designing the new curriculum would take into account Teko-Guaraní’s guiding principle: Considering first the needs of the community. Bolivia cannot afford to overlook the vast cultural diversity of its citizens in favor of composing a curriculum that represents only one group. Truly encouraging children to respect and take an interest in different cultures comes through opening oneself up to new ideas, faculty at Teko-Guarani argued. Though I am by no means an expert in educational reform, my research led me to participate in a special initiative: “Kids’ Books Bolivia,” a project that provides students the opportunity to write, illustrate, and publish children’s books that promote multicultural understanding and tolerance. While "Kids’ Books” was founded in the country’s Andean region, I choose to make my book about an Amazonian topic. Based on my research, I felt it was important to make a special effort to emphasize the significance of the (sometimes underrepresented) Amazonian cultures. (Even among the several dozen books that previous students have published working with the project, notably only a handful have covered Amazonian topics.) The book on which I worked takes the traditional Guaraní legend of the chöcho, a bird believed to have the power of augury, and reintroduces it to a wider audience in three languages: English, Spanish, and Guaraní.