Rediscovering Rush

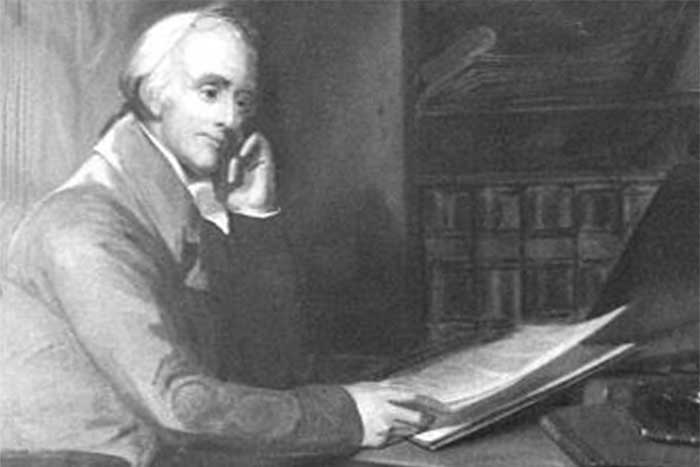

Benjamin Rush (1745-1813).

by Matt Getty

Who gave Thomas Paine the title for Common Sense?

Which signer of the Declaration of Independence helped establish the nation’s first abolition society?

Who was one of the first doctors to recommend that the mentally ill should be treated rather than imprisoned?

You’d think that any Dickinsonian facing these questions on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire would break the bank. After all, the college’s founder, Benjamin Rush, is the final answer for all three. Anyone who’s attended Convocation, returned for Alumni Weekend or talked to President William G. Durden ’71 for a few minutes knows everything there is to know about Rush, right?

Not quite. “Most of us know a little,” says Jeremy Ball, associate professor of history. “We know that he signed the Declaration of Independence, that he was a doctor, that he founded the college, but that’s about it.”

And, for Ball, that’s also a problem. “It seems if Rush is so central to the narrative of the college, we should know more,” he continues.

To help the Dickinson community better understand its founding father, Ball teamed with Joyce Bylander, special assistant to the president for institutional and diversity initiatives, and Susan Rose ’77, professor of sociology, this spring to create the Benjamin Rush Study Group. Meeting five times during the summer to discuss Rush’s writings on public health, slavery, education and government, the 15 faculty and staff members in the group examined the positive and negative aspects of Rush’s life.

“It’s important to look at him in his complexity,” Ball explains. “You want to be careful that the narrative doesn’t just become hagiography.”

That means that in addition to discussing Rush’s fight for abolition, the group confronted his more troubling belief that black skin resulted from leprosy. During the same session in which participants discussed his heroic efforts to treat victims of Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow-fever outbreak, they also wrestled with his ardent defense of bloodletting as an effective medical treatment.

The intent isn’t to disparage Rush, Ball explains, but rather to capture a fuller picture of the man on the bronze pedestal. “We know all the parts of Rush’s character that we’ve tapped into as part of Dickinson’s story, but there’s a whole person there that goes well beyond that,” explains College Archivist Jim Gerencser ’93, who helped Ball launch the study group.

To reveal the real Rush to the wider community, the study group has urged the college to follow up on its work by integrating Rush into the curriculum. “There could be a first-year seminar about Rush or common readings for incoming students,” Ball explains. “We could use him as a prism for examining broader contemporary issues, or as a model of the engaged citizen.”

One potential outlet for these efforts is the new Benjamin Rush Gallery, which opened in the Waidner-Spahr Library in May. Adjacent to Archives & Special Collections, the gallery displays the Thomas Sully portrait of Dickinson’s founder, which Rush descendant Lockwood Rush conveyed to the college in 2009. In addition to the painting, the gallery’s current exhibition, Benjamin Rush & Dickinson College: Building Our Destiny, displays Rush’s letters to John Jay and John Dickinson, 1786-87, cash-ledger accounts for the college and other items related to Rush’s work establishing Dickinson.

Gerencser and Phillip Earenfight, director of The Trout Gallery, have discussed creating an internship that would allow students to update the exhibition annually, but the portrait will remain on permanent display.

“It’s a pleasure to see that the portrait has been a real catalyst—that this beautiful gallery has risen up around it,” says Lockwood Rush, who attended the May opening with his wife, Jacklyn. “We both feel very strongly that it’s the perfect home for Benjamin Rush.”

Rush recently found another permanent home on campus—on a historical marker outside the gate on the corner of High and West streets. Featuring a brief biography as well as images of the Sully portrait, Old West and a page of Rush’s writing, the marker was unveiled this fall.

“It’s important to have these visible reminders on campus,” Gerencser says. “We hear about Rush in President Durden’s speeches. We read about him in the magazine, but—like the statue [erected in 2004]—this marker and the gallery help to give Rush a real physical presence at Dickinson.”

The importance of that physical presence and the fuller Rush story sought by the study group, say Ball and Gerencser, goes beyond their potential to help a Dickinsonian answer one of those million-dollar questions without needing President Durden as a lifeline.

“The more we learn, the fuller our picture of Rush gets,” explains Gerencser. “And as that picture gets fuller so does our understanding of Dickinson and its history.”

Published October 3, 2011