Relentless Resilience

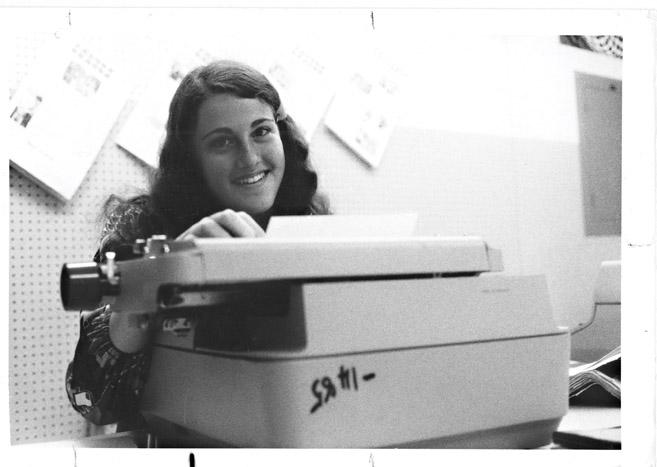

Stephanie Greco Larson

Stephanie Greco Larson's posthumous memoir gets its due

by Michelle Simmons

Stephanie Greco Larson had been married just six months and was directing Dickinson’s humanities program in Norwich, England, when she received her diagnosis of inoperable cancer.

“It was December 2006,” recalls David Srokose, Larson’s husband. “She got the first bit of chemo in England, January to June, and when we came back [to the U.S.] in August 2007, she was back in chemo by September. From that point forward, pretty much until she went into hospice March 2011, she had 27 different courses—types, combinations—of chemo. She never had a remission, any pause in her treatment.”

Larson’s experiences with the medical establishment had been negative her entire life —from a childhood knee injury that never healed properly and a ruptured appendix with multiple complications to what was now a second cancer diagnosis. She struggled not only with the illness and her doctors but also with a culture that insisted on cheerful acquiescence to unhelpful—and often painful and unnecessary—procedures and treatments. In 2009, she began writing a narrative of those experiences, using her keen eye and academic training as professor of political science and women’s & gender studies to question the system in which she felt trapped. The result is Relentless: One Woman’s Story of Betrayal by the Medical System, due out Feb. 1 (see excerpt below).

Like writers and cultural critics Susan Sontag and Barbara Ehrenreich, Larson resisted the conventional illness narrative. “Not only are my attitudes about health care at odds with most people’s,” she wrote, “but my attitude about my attitudes seems to be as well. … [People] tell me that if I stay positive, everything will improve—I’ll be happier while having cancer, and if I believe that I will get better, my body may miraculously heal. … If I refuse, falter or ultimately fail to ‘stay positive,’ am I complicit in my own demise?”

Along with sharing the story of her noncompliant body, Larson questioned what she considered dubious research on positive thinking, explored the ongoing health care debate and analyzed media portrayals of cancer patients. (On Sex and the City: “Samantha never looked tired,” wrote Larson. “She only occasionally seemed scared. And my personal pet peeve—she kept her eyebrows.”)

Larson completed a draft of the manuscript and was working on its organization when she died in June 2011. After Srokose established a Dickinson scholarship fund in her memory, he also decided to bring the manuscript to print, with the assistance of her colleagues and former students. All net proceeds from its sale would go to the scholarship fund.

“When she started writing this, she wanted to have it published,” Srokose says. “I don’t remember exactly whether there was this moment, a dying promise, but it was understood that after she was gone, the book was going to be one of the things I was going to do for her.”

So Srokose reached out to Meghan Allen ’08 and several of her classmates who had studied in Norwich with Larson and later become close friends. “I got to know her as a mentor while I was there,” says Allen. “Larson was so comfortable with who she was. When you’re at that age you really value those people who have found their place and become OK with themselves.”

Allen, who teaches at Aberdeen High School in Maryland, agreed to be the primary manuscript copy editor. Amy Farrell, professor of American studies and women’s & gender studies, wrote the foreword and afterword. Although the story is grim, it also is “funny, blunt, analytic, unflinching, honest and, above all, fully human,” notes Farrell. “It’s important, I think, to describe what a good friend, what a keen scholar, what a quirky, humorous, energetic and vivacious person she was.”

Vickie Kuhn, senior academic department coordinator for political science and sociology, shepherded the entire process, including recommending Laura McCauley ’13 as cover illustrator and designer. Chris Eiswerth ’08 handled some of the final editing, and Jill Boland Roberts ’08 designed and administers the book’s Web site.

“Her story really is a manifestation of the person she was,” says Allen. “That person was someone who didn’t just accept things as they were. She asked questions and answered them without fear.”

Excerpt from Chapter 1

People seem rattled when I fail to hide my ugly truth by saying “fine” when they ask me how I’m doing. I might say “hanging in there,” “better than I was last month” or “not great.” None of these answers conform to the bright side they want from me.

None of the responses celebrate the fact that I am “still here” and the idea that surviving at any cost is good news. I don’t know what to call my bluntly honest approach—is it brave or cowardly? Is it self-centered or useful for others? Is it a gift to my family and friends or a gift from them to me? Maybe it is all of these things. I know it is not polite. But it’s never polite to challenge conventions, to say things that people don’t want to hear and that make them uncomfortable. That’s what I am doing. In my profession we call this “resisting the dominant ideology.”

My medical experiences and my academic training have resulted in a perspective on having terminal cancer that is so different from my father’s. We use a lot of fancy terms in academia. When we can’t find the right words we make them up. We construct “arguments” and “deconstruct” images, commercials, entertainment and rhetoric. We “critique” everything, including each other. It’s a whiny profession when you think about it. But these skills help us “see” ideology rather than see “through” ideology.

Ideology is belief about how the world works and how it should work. Ideology privileges certain ideas, behaviors and even types of people, groups or countries. For example, patriarchy is an ideology that believes that men are more worthwhile than women. If you believe in patriarchy, then gender inequality “makes sense” and is even just. Of course there would be more men in positions of power if men have more skills and aptitude for leadership. The ideology normalizes the inequality. It makes the inequality invisible. It reassures us that the world is working the way it should when we see something that seems wrong. Once you look “at the ideology” instead of “through it,” you notice lots of inequality. It can make you angry and frustrated when other people don’t see it.

Once I became chronically and terminally ill, I started to see an ideology about health, modern medicine and cancer. I saw how the ideology and the actions and words that went along with it oppressed me (and other patients, whether or not they recognized it). I see how the positive-thinking mantra and the “fighting a battle” analogies that permeate discussions about cancer encourage those of us who are dying from cancer to feel responsible for our “failure.”

My medical experiences are only part of my life story. They have been the saddest parts—some of them longer than others. The rest of my life has been pretty wonderful. I came from a loving, stable family. I have always had great friends. My professional life has been fulfilling and enjoyable. I have been financially secure. I have never stopped learning. I know, and like, myself. Finding a life-partner wasn’t easy, but the search has had some highlights, and I ended up finding a wonderful mate. Now that I have terminal cancer, the foreground of my life story seems to have become the background. It feels disorienting.

I wish that my medical life experiences were a smaller part of my life story. One way that could have happened is if I hadn’t gotten sick or injured so often. I don’t spend much time thinking about that. It would lead to me blaming my body for being fragile when I can accept that that’s how bodies are. I remind myself how resilient and strong my body has been too. It has done the best that it could. So, I spend more time appreciating it than blaming it. I think that no matter what we do, things happen to our bodies. Some people are luckier than others. I marvel that my husband has never had an IV and that a friend in her 60s was only hospitalized when she gave birth to her daughter. I lament the students I have had who have died of AIDS, car accidents and in Iraq not long after I taught them.

Another way that my medical life experiences could have been a smaller part of my life is if the health care system had treated me differently. I have been repeatedly victimized by the medical profession, and it has led me to anticipate the worst from medicine. Despite my vigilance and assertiveness (perhaps, in part, because of it), I continue to get hurt by it. Many of my physical problems have been caused or exacerbated by medical treatment. Drugs seem no more likely to help me than to hurt me. My life has been risked as often as it has been saved by what doctors have done. More than my injuries or illnesses, it is this long-term abusive relationship with doctors that haunts my life story. —Stephanie Greco Larson

Learn more about Relentless.

Read more from the winter 2014 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Published January 15, 2014