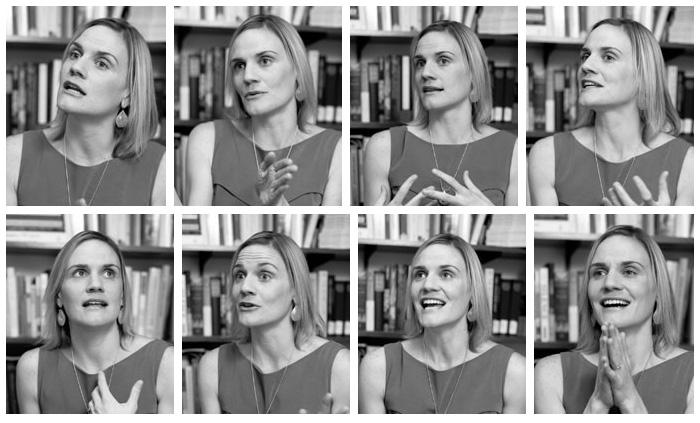

Claire Seiler

Focus on Faculty

by Christine Baksi

How did you develop Midcentury Suspension, your forthcoming book about literary culture in the decade after World War II?

I followed a hunch. I didn't see the distinctive energies of midcentury writing reflected in the scholarship about it. I started thinking about how to counter the general impression that the midcentury either watched modernism die or saw postmodernism start—that the midcentury was kind of boring, really. The only way to go was plain old archival research, which any scholar will tell you is a complete blast. There was a sweet time when I got to refer to a Netflix queue stocked with movies of the late 1940s as "work." I read as much as I could of the period—the whole runs of magazines like Life and The New Yorker from 1945 to 1955, for example—and all with an eye to figuring out how midcentury writers thought about their moment. In the course of that reading, I found some unexpected literary events, such as when Horizon, a fairly snooty British magazine, published the first piece of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man in 1947. You have to ask yourself: What is one of the great American race novels doing there? I wanted Midcentury Suspension to dig into the implications of such finds, rather than tidy them up.

How does your midcentury project complement your teaching?

Midcentury Suspension practices what we teach. It's about paying attention to the cultural work that words do. One of the tenets of critical thinking in the liberal arts is that the bigger the "ism," or the more pervasive the buzzword, the greater the need to question it and historicize it. But that also holds true for the apparently unremarkable terms that do a lot of our analytical work for us. Those mundane terms like "midcentury" often allow us to make exclusions or assumptions without explicating them—particularly exclusions or assumptions that consolidate racial, national or gender sameness.

My next project considers the effect of another such organizing term, "generation," on poetry from World War I through the poems that our Millienial students are producing. In English courses, we push students to think about such received linguistic and cultural forms as sites of inquiry, rather than as givens.

The simpler answer is that I'm teaching a course this spring called Poetry of the Mad Men Era. Don Draper is a big fan of Frank O'Hara.

There's a fascinating personal story of love and war that's inspired your work.

My maternal grandfather, Arthur Newcomer, served in the Navy in World War II; my grandmother, Eleanor Cupler, was in the WAVES, stationed in Seattle. Arthur's battleship, the USS Trathan, came into port in Seattle for repairs just before V-E Day. They fell in love, but who knew what would happen? Like all men in the Navy, Arthur was anticipating the invasion of Japan. Flash-forward less than a year, and their marriage announcement appears in the tiny Bryan Times (Ohio). The young Navy couple, it read, was "setting sail on the seas of matrimony."

The remarkable thing is that Eleanor wrote home to her parents in Chicago every single day while she was stationed out west. Can you imagine? We have 1,000-plus pages of letters in her wry, candid voice. (Eleanor had been a public school teacher before the war and was, throughout her life, a great reader and writer.) The first letter quotes Longfellow's "Psalm of Life," which every American who grew up during the Depression would have known. One of the much later ones describes a blind date with this handsome, funny man, Arthur.

My grandmother and I wrote letters back and forth about books from when I was nine or so until she died, which was just as I was devising my dissertation. That's when I first found her letters home from the war, and that's when I started trying to figure out what those initial postwar years must have felt, sounded and read like. Eleanor is my primary source.

You blog for Arcade: A Digital Salon. The immediacy of it is a departure from a multiyear project like Midcentury Suspension. How do you adjust?

With a sense of relief! Academic publishing is s-l-o-w. It has to be. Good work needs the processes of hard thought, research, drafting, revision, conference presentations, peer review and percolation. Arcade is about sustaining conversation, and its timeline is productively compressed. It's one of many digital sites at which the humanities demonstrate, rather than only defend, their vitality.

You teach yoga for faculty and staff here at Dickinson. Does yoga ever find its way into your academic classrooms?

That is a tempting thought. I love the idea of starting my 8:30 a.m. class with sun salutations. My teaching yoga here is an extension of my daily practice, which centers me and gives me (like all academic yogis) a way of getting out of my head. Yoga comes into the classroom as soon as I do. Teaching requires all kinds of balance: direction and patience, discipline and flexibility, steadiness and energy. Yoga cultivates that. And like good thinking, yoga is all about extending, clarifying, finding limits and moving past them. And here's where I have to say, "Namaste."

Published November 20, 2012