Dickinson College

Now You See Him

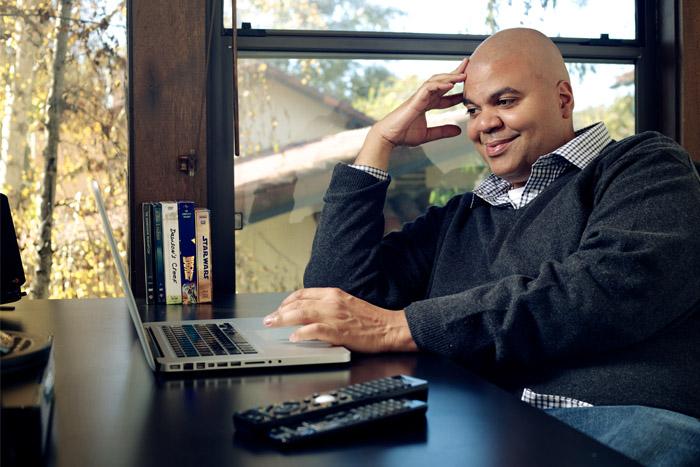

Edward Ricourt '95

by Matt Getty

Edward Ricourt ’95 pulled his rental car to a stop along Bourbon Street, just outside a ring of trailers glowing under a halo of light. Throngs of people milled about, assembling more lights, moving cameras, positioning crowds.

Among them, Ricourt knew, were Morgan Freeman, Woody Harrelson, Michael Caine, people he’d grown up watching in movies he dreamed he’d one day write. People who’d inspired him to become a screenwriter, move to Los Angeles, write script after script, selling enough to make a living but not yet seeing anything climb from “development hell” to production.

Until now.

“That was the moment,” says Ricourt, recalling his visit to the set of Now You See Me, which will bring his words to the screen for the first time this summer. “I had the goose-bumps, the tears in my eyes. I just thought, ‘This is real.’ Hundreds of people uprooted their lives to be here, all because of something I wrote on my MacBook in the middle of the night. It felt like the completion of a very long journey.”

That journey began at Dickinson, where Ricourt majored in political science but discovered a passion for writing in fiction and theatre classes. By his senior year, he felt ready to tackle something substantial. A friend suggested he write a screenplay, so Ricourt approached Professor of Theatre Todd Wronski, who helped him design an independent study on screenwriting and write his first script.

“It was a great experience,” Ricourt recalls. “It was life-changing.”

Ricourt left Dickinson having found his calling, but it would be another decade before Hollywood beckoned. He found work in New York City as a production assistant and then associate producer for The Ricki Lake Show and spent his nights poring over every great screenplay he could find while plugging away at his laptop.

He shared that first script with his friend, screenwriter and director Boaz Yakin. Yakin, who soon would have his own major breakthrough directing Remember the Titans, loved Ricourt’s writing, and the two launched a partnership.

When Yakin formed a production company after his success with Remember the Titans, he tapped Ricourt to pen its first film. Ricourt turned out the horror flick, Dead by Daylight, which was optioned and landed him an agent. Yet to be produced, however, the script also taught Ricourt a valuable lesson.

“The more successful I’ve gotten, the more I’ve learned how hard it is to see your screenplay become a movie,” he says. “When I sold my first script, I thought, ‘Great, they’re going to make my movie,’ but the truth is, you’re almost just as far from making a movie as you were before you sold it.”

After receiving pages of notes on proposed changes, Ricourt learned that even successful screenwriters must wait until the studio attracts the right talent to a script. The longer that development process takes, the less likely that glowing late-night laptop vision will ever make it to the big screen.

Still, Ricourt refused to be discouraged. He earned an MFA in dramatic writing from NYU in 2005 and made a leap of faith the day after graduating, flying to L.A. with only two months’ rent to his name.

Ricourt found his footing quickly in Hollywood. He captured studios’ imaginations—and paychecks—with tales ranging from a post-alien-invasion human uprising (Year 12) to a widow plagued by visions of murdered children (Abraham’s Daughter), but none made the leap from meeting rooms to celluloid. He was living half the dream, making a living without actually making movies—until his most recent collaboration with Yakin, the story of a team of bank-robbing magicians, found a buyer and a little bit of luck.

“We sold Now You See Me, but Jim Carey had passed, Sacha Baron Cohen had passed, and we were getting a little worried,” he explains. “But then Jessie Eisenberg said yes, and the dominos started to fall. Morgan Freeman, Woody Harrelson—one after another, people started signing on. That was a huge relief.”

Last spring Ricourt arrived in New Orleans to ponder the next step in his journey. He didn’t bask for long in the glow of those lights, the circle of trailers, the crowds of people seemingly conjured by his late-night typing. He’d arranged to spend a month on set so that he could learn enough to try his hand at directing and producing future projects, and it was time to get to work. With a career always teetering between triumph and frustration, he strode toward those trailers quickly, having learned long ago to keep moving forward.

“You have to realize it’s a marathon, not a sprint,” Ricourt says. “You can’t worry about rejections or frustrations. I’ve got files filled with rejection letters. I’ve sold scripts where the first meeting was about who was going to replace me as a writer. But I always knew I just needed to work harder than the next guy. I knew when I was working at two in the morning, my competition was sleeping. I always knew I just had to keep going.”

Published January 11, 2013