Faster, Smarter, Better

Student-faculty research streamlines chemical processes

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

July 23, 2013

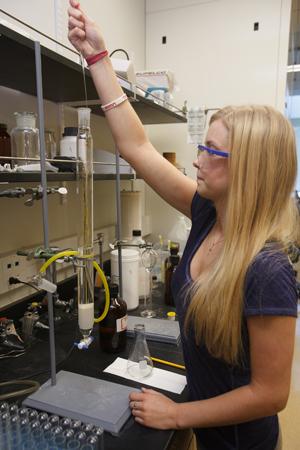

Allyson Boyington '15 performs research as a summer organic-chemistry intern as she prepares for a career in pharmacology or toxicology."Organic chemistry is a large part of both of these fields, so I was very excited to be able to further explore what I had studied in the classroom this year," she says.

Allyson Boyington '15 performs research as a summer organic-chemistry intern as she prepares for a career in pharmacology or toxicology."Organic chemistry is a large part of both of these fields, so I was very excited to be able to further explore what I had studied in the classroom this year," she says.

If a chemical product such as a new pharmaceutical cannot be created efficiently, it may not be created at all. Professor of Chemistry David Crouch and his students offer a possible solution by streamlining lengthy chemical processes used to develop many new products.

Using microwave irradiation to accelerate a complex process often used in pharmaceutical development, they've been able to condense a procedure that would typically take 18 hours to just 30 minutes. It’s a tricky affair, as they must simultaneously induce a reaction in one targeted molecule or portion of a molecule, known as an alcohol, while ensuring that other alcohols within the same substance remain unaltered.

“The approach that organic chemists take is to make that alcohol inactive by temporarily turning it into something else,” Crouch says. “After the reaction that was originally intended is complete, we remove the protecting group.”

Allyson Boyington ’15, who majors in environmental science, chemistry and biochemistry & molecular biology, is working with Crouch this summer to test the accelerated procedure. She quickly learned that the world of research differs considerably from her previous experiences in science labs.

“The labs that students take with classes have been tested multiple times and are designed to work—and they usually do—but research experiments don’t always yield the desired products,” says Boyington, who plans to pursue a career in either pharmacology or toxicology. “It becomes a trial-and-error process, and it’s very rewarding once the optimal conditions are found.”

Learn more:

Published July 23, 2013