Dickinson College

Revisiting “Capturing the Quotidian”

The following story was published in the winter 2006 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

by Sherri Kimmel

There he is in his well-worn cotton shirt, jeans and comfortable high-tech shoes, ordering up some hand-crafted cheese. He's happy to stand and chat. Conversation is relaxed. After all, this is Carl, who epitomizes the adjective mellow. But now and then you'll see his blue eyes light on something just over your right shoulder, like those adolescent boys goofing around at the soft-pretzel counter. Suddenly the Leica you didn't notice before is at Socolow's eye. Click. He lets the camera dangle again, and chats on.

He's been doing this for years, street photography he calls it. Capturing the quotidian. He'll even venture into pubs, where photographers have been known to get their cameras smashed by patrons doing things they don't want documented. When saloon-goers get testy, Socolow just says he's working on a project about everyday life. From 1998 to 2003 he sought the commonplace mainly in central Pennsylvania. But a chance encounter with some hand-thrown clay pots led him to bring his inquiring eye to a remote Mexican village, 11 times and counting.

A professional photographer doing work for Hershey Foods, Holy Spirit Hospital and a host of other businesses and institutions for two decades, Socolow turned street photographer when he realized he was "burning out on commercial work and didn't want to lose my passion for it. I started doing work for myself, which involved keeping the camera with me at all times for whatever would speak to me of the Zeitgeist of the times in which we live."

Meeting a Tucson pottery trader led Socolow to the project that has brought him to Mexico every three months since March 2003, to learn Spanish, adopt the nickname El Gallo (the rooster) and have a Mimbres (Mesoamerican-style) rooster tattooed on his left biceps.

Socolow and Holly, his wife of 19 years, were visiting Carl's college friend Jeannette Faunce '77 and her husband in Maine, where they own a pottery shop. Also visiting was Tito Carrillo, who had brought cases of pottery from Mata Ortiz in the high Chihuahua Desert of northern Mexico. There, 50 years ago, a teenage boy, Juan Quezada, resurrected the primitive techniques used in the pottery of the Paquime, or Casas Grandes culture, circa 1150-1450, and made it into a contemporary art form. Quezada shared his craft with family members; today more than 400 of the 3,000 villagers are potters. Carrillo urged the Socolows to visit the village, telling Carl, "You'd be able to make good pictures."

When Carrillo revealed that the village was getting its first paved road, thanks to its pottery-fueled prosperity, Socolow was sold. "It was a village in the throes of change because of its art, and its art was singularly unique to the village. The government was using it as an economic engine to drive development and tourism throughout the region."

Since their first visit in 2003, Holly and Carl have filled their living room—painted in the rich blues and golds of southern France, a few Mexican tiles set into the walls—with dozens of Mata Ortiz pots. They delight in pointing out the different styles, some of which are anthropomorphic, and the fact that all, no matter how intricate or simple in pattern, are painted with a single-hair brush. The pots can range in price from $10 to $5,000, the latter if created by founding potter, Jose Quezada, who serves as the village paterfamilias. The Socolows have yet to purchase an original Quezada.

But even more plentiful than the pots are the images. Socolow typically shoots 25 to 40 rolls per weeklong visit. Though he's gone digital in his commercial work, he relies upon two film-burning Leicas to tell the village tales he encounters. Film has permanence, whereas digital archiving is still evolving, he explains.

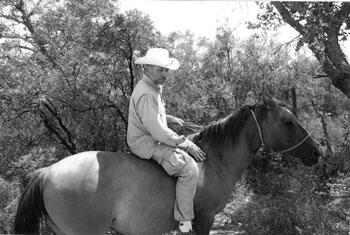

Known as El Gallo by the villagers, Socolow is no longer a strange guero (light one) but a friend invited to weddings and funerals, horse races and bull-riding contests, town meetings and Day of the Dead cemetery cleanings. The people of Mata Ortiz now anticipate each visit, eager to see the prints from his last trip.

Back in his colorful Camp Hill, Pa., living room, Socolow lays out 20 matted 11-by-14 prints that he is submitting for an arts grant. His hope is to obtain travel funding that will allow him to continue his project, with the ultimate goal of publishing a book.

Using the medium of classic slice-of-life photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson, Diane Arbus and Walker Evans, Socolow's images are black and white. He considers it "more poetic, a stronger use of form that directly involves the viewer. The viewer has to interact with the photograph. Color is great if you want to see the color of clothes, but black and white gives insight into the soul."

Socolow's photos, which seem a bit off-kilter in composition to viewers accustomed to perfectly centered images, reveal what he sees out of the corner of his eye. Boys play, haphazardly ranged across the frame, echoing the famous Cartier-Bresson image of boys playing in the street in 1933 Seville, Spain. Few of his thousands of negatives depict the pottery that has made the village a tourist destination in recent years.

"I'm not working to photograph pottery being made," Socolow asserts. "I'm interested in the quotidian aspect. What is it like to live in this village?" And so what he reveals is mothers readying their children for school, typical cowboy/potter residents in Western-style boots, cowboy hats and belts having morning coffee with friends.

While the work of the great street photographers inspires him so do imagist poets like Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, plus the detail-driven Marcel Proust, and Charles Dickens with his strong character development. Not at all surprising for a Dickinson English major.

"I'm trying to create a visual story about this world," he says. "If I ever make a poem as succinct and true as William Carlos Williams' 'The Red Wheelbarrow' I will feel I have accomplished everything I have strived to do."

Despite some commercial workshops, the only formal training Socolow has had are two courses at Dickinson. He came to college from the East Shore of Harrisburg, having fallen in love with photography at age 15, when he visited a friend's darkroom. "The first time you see a photo come up in the developer it's magical. It snags you," he says.

For a year after graduation he worked in Carlisle in a hardware store to get in touch with everyday life, then as a reporter-photographer at a weekly Perry County, Pa., newspaper. He worked for The Patriot-News in Harrisburg before founding Socolow Photography in 1984.

Now, one year after the paved road reached Mata Ortiz, Socolow is waiting to see how progress and greater wealth affect the people, whom he cherishes for their openness, directness, sincerity and simplicity.

"One of the questions is, will the innocence that I have found in this village endure? From my perspective there's a danger of romanticizing the change from a simple village life to prosperity. I'm seeing signs of greater materialism but, fundamentally, these people are looking for security."

And Socolow is looking for a visual story that has no end in sight.

"People ask when will I be done. To impose a deadline is shortchanging it. [Eugene] Atget photographed Paris for years, showing what life was like at the time. What art aspires to define is life at the time the art was created."

Published October 1, 2012