Reclaiming History

Digital archive opens a new chapter for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s descendants

by Rick Kearns

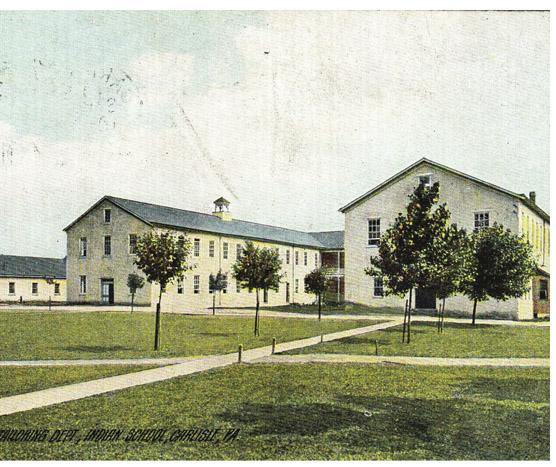

A mere few miles from Dickinson, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (CIIS) was founded in 1879 to “civilize” American Indian children by teaching them to assimilate into American society. Over the course of 39 years, the school took in approximately 10,000 children from 140 tribes — many of them forcefully.

Image courtesy of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

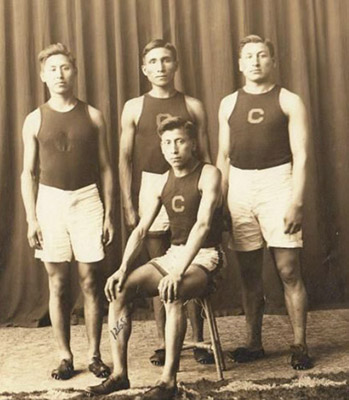

Of those who attended, many entered careers as teachers, tradesmen and athletes — including Frank Mount Pleasant, Dickinson class of 1910, who competed in the 1908 summer Olympics in London. Others, cut off from their native languages, identities and families of origin, entered a legacy of trauma and disenfranchisement. All of them have stories to tell, and now, more than 130 years later, their descendants, as well as researchers and archivists, have unprecedented access to those stories.

One of those descendants is Rene Garcia, who learned about her grandfather, Peter White, and other Mohawk ancestors who attended the CIIS, through the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, a Dickinson-hosted Web site dedicated to posting all available records of the children who attended the school between 1879 and 1918.

The Dickinson team members behind this ambitious project include Susan Rose ’77, professor of sociology and director of the Community Studies Center; James Gerencser ’93, college archivist; Malinda Triller Doran, special collections librarian; and a multitude of students and recent alumni who have traveled to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, D.C., to scan more than 4,400 CIIS student files so far, totaling about 60,000 pages of records — two-thirds of the total amount on file. Barbara Landis, historian at the Cumberland County Historical Society, as well other local CIIS experts, is lending her expertise.

The project is funded by Dickinson’s Research & Development Committee and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Digital Humanities grant, which supports the researchers’ travel to D.C. to scan and digitize the records. Gerencser says that they also plan to build partnerships with other institutions that may have photos, letters or other items connected to the school as well as with descendants of the CIIS students and other researchers. So far, more than a few viewers have come forward with photos and other mementos.

“It was exciting to see the student records online that I wouldn’t have access to unless I wrote to NARA,” says Garcia, adding that she learned of the site through the CIIS Descendants, Relatives and Friends Facebook page.

“My grandfather was the first name I searched for, and it came up immediately,” she continues. “I learned that he was discharged for being irresponsible, and my mother told me that he was not happy during his time there. He went on to become an iron worker and was one of the Mohawks who helped build the Empire State Building. He was even president of the local Mohawk ironworkers union. His son went on to become the first Mohawk Catholic priest from St. Regis and in the U.S.”

Garcia also found records of her grandmother’s father and nine other relatives. “For many of us, our grandparents’ time there is a mystery,” she says. “To see parents’ and even grandparents’ names in these records was breathtaking. To see Mohawk names long forgotten was something I never expected.”

Cheyenne Chief (Manenmic) one of Florida prisoners. Image courtesy of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

“Not much is known about my great-grandmother,” explains Joan Adolph, another database visitor. “Her name is Rose Dion, and she was Rosebud Sioux. She did not graduate. I love looking at the pictures and wondering about her. I just found out last July that she went there.”

Dickinson faculty and students also have been taking advantage of the different materials available on the site, which has separate pages for student files, images, publications, collections and Web sites. Alan Shane Dillingham, visiting assistant professor of history, used the site in his course Native Histories of the Americas, in which students learn about the lives of individual CIIS students and present their research to their classmates.

“It’s been a really exciting experience,” Dillingham says, explaining that the course is organized around certain themes, one of which was how the tribes shifted from isolation to a type of inclusion, integration and, to a certain extent, assimilation.

Dillingham brought in Landis to provide some context to the CIIS story, and he ensured that there was a good variety of choices in terms of geography, gender and other categories for his students.

“I wanted them to appreciate the stakes,” he says. “There was coercion and violence involved in [the CIIS] students’ lives, but there were also moments of humanity, of the young people learning useful skills.”

One of Dillingham’s students, Mackenze Burkhart ’15, a double major in archaeology and anthropology, researched the life of a remarkable Carlisle student, James M. Phillips (Cherokee). “What I found to be significant about Phillips is that unlike the majority of narratives we read in class, Phillips’ story is one of success and happiness,” she says. “Phillips entered the school in 1901, but only to participate in athletics, as he was an extremely talented football player,” Burkhart explains.

“Phillips attended the Dickinson School of Law and graduated in 1903, the same year he left the CIIS,” she continues. “He married a graduate of the CIIS, Earney Wilber of the Menominee tribe, and then attended Northwestern University. While at Northwestern he played football and earned the title of Best All-Western Guard. After graduating, he moved to Washington where he started his own law firm. He later served as police judge, justice of the peace, mayor of Aberdeen, and the Grays Harbor County Superior Court Judge. Phillips is now considered the first American Indian to serve as a judge in the Washington court system.”

Burkhart notes that she already had known some American Indian history before taking Dillingham's course, as that field has been an interest of hers for years. “However, in hindsight I can honestly say I barely knew anything about the CIIS and Indian boarding schools in general,” she says. “I was struck by the fact that Indian boarding schools have gone by relatively unnoticed by many Americans and that the topic is largely evaded in K-12 education.”

Burkhart also learned some of her own family history researching the story of James Phillips. “My grandmother, who grew up in Bethlehem, Pa., mentioned that she remembers her church collectingclothing to donate to the CIIS,” says Burkhart. “I love making connections, and I found it extremely exciting to have a small, but personal, connection to my research.”

Those connections will grow as the research and digitization team continues its work.

“The CIIS student records going online have provided many of us with a snapshot of our ancestors’ time there — something we wouldn’t have had otherwise,” says Garcia. “I am extremely grateful for all those whose hard work and dedication has made this possible and truly thank them for this.”

Learn more

Read more from the summer 2014 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Published July 22, 2014