Jim Thorpe Center for the Futures of Native Peoples

View MenuFederal Boarding School Annotated Bibliographies

In Fall 2023, Dr. John Truden taught American Studies 200: Indigenous Peoples and Federal Boarding Schools in the United States. In that course, each student assembled annotated bibliographies on a specific federal boarding school. These bibliographies were designed to be accessible to Indigenous communities. Each bibliography includes a description of a particular school along with descriptions of primary sources and second sources relating to that institution.

** Disclaimer** The bibliographies are in their original format and have not been modified. Minor numbering and spacing changes occurred when transferring materials to the website.

Haskell Indian Nations University

The Haskell Indian Nations University of Lawrence Kansas, more commonly known as Haskell, is a historically significant Native American University. It is one of the oldest American Indian boarding schools in the country, opening its doors in 1884. Within the history of Native American education, cultural preservation, and self-determination, Haskell has been a key figure. The federal government wanted to assimilate Native American children into the mainstream of American civilization in the late 19th century. It was founded as a United States Indian Industrial Training School to give Native American students access to vocational training. The curriculum emphasizes industrial and agricultural trades and vocational skills. Haskell's mission has changed dramatically over time. Currently a tribal college, Haskell Indian Nations University serves as a center for Native American higher education and cultural preservation. Its goal is to give indigenous students access to quality education that will allow them to maintain and build their cultural identities while prepping them for success in a multicultural, global society.

The Haskell Indian Nations University of Lawrence Kansas, more commonly known as Haskell, is a historically significant Native American University. It is one of the oldest American Indian boarding schools in the country, opening its doors in 1884. Within the history of Native American education, cultural preservation, and self-determination, Haskell has been a key figure. The federal government wanted to assimilate Native American children into the mainstream of American civilization in the late 19th century. It was founded as a United States Indian Industrial Training School to give Native American students access to vocational training. The curriculum emphasizes industrial and agricultural trades and vocational skills. Haskell's mission has changed dramatically over time. Currently a tribal college, Haskell Indian Nations University serves as a center for Native American higher education and cultural preservation. Its goal is to give indigenous students access to quality education that will allow them to maintain and build their cultural identities while prepping them for success in a multicultural, global society.

Historical sources related to the Haskell Indian School, now Haskell Indian Nations University, can be found in various archives that are dedicated to preserving the history of Native American education. One significant resource is the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), which houses government documents, reports, and correspondence relevant to the boarding school era. Haskell's own archives and library, often found on its official website, contain photographs, publications, and records that provide insights into the institution's history and development. Additionally, the Kenneth Spencer Research Library of Kansas and the Waidner-Spahr library house an immense collection of Haskell resources. Local historical societies like the Carlisle Indian school digital resource center also offers an array of digitized materials that includes letters, photographs, and narratives from the Haskell Indian School. These resources collectively serve as invaluable tools for researchers, students, and individuals interested in understanding the complex legacy of Native American education in the United States.

Primary source 1

National Archives of Kansas City

Record Group 75

Records of Haskell Indian Junior College, 1970-1993

These are Student case files collected from Haskell Junior college and the Haskell institute from 1884-1980.

Records of Haskell Institute, 1887-1947

These records include correspondence between school officials and the office of indigenous affairs as well as Student records and extensive financial records.

Records of Haskell institute, 1947- 1970

These records include Federal correspondents, financial records and even documentation on graduated Haskell students who fought in WWII.

Primary Source 2

Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas

Wallace Galluzzi Papers

Papers from administration during a time of change for Haskell Indian Junior College

Primary Source 3

John L. Glinka Correspondents

These papers refer to the Kansas state evaluation of Haskell Institute from 1969- 1970

Primary Source 4

Carlisle Indian school Digital Resource Center, Documents produced by Carlise archive officials and students that pertain to Haskell

https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/external-groups-and-institutions/haskell-indian-school

Carlise Indian school digital resource center is an amazing tool to use whenever you are researching any details dating back to the days when school was in session. The plethora of documents consists of all sorts of student and faculty literature, art, letters and so much more.

Primary Source 5

Haskell Cultural center and Museum

Collection includes Printed or published, unpublished, archival, and manuscript collections, audio/ visual collections, microfilm, finding aid, historical objects, fine art

Secondary Resources

WILBUR, R. E., CORBETT, S. M., & DRISKO, J. A. (2016). Tuberculosis morbidity at Haskell Institute, a Native American Youth Boarding School 1910–1940. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 40(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12092

This Article shares disparities in tuberculosis and morbidity within Indigenous children living in close quarters with a multitude of cultures

Vučković, M. (2008). Voices from Haskell: Indian students between two worlds, 1884-1928. University Press of Kansas.

This book offers direct insight into the day-to-day life of children going to school at Haskell. The book gives detailed analysis of the dialogue written by students, parents, and faculty.

[Grant Peter], “A 1918 Influenza Outbreak at Haskell Institute:” An early narrative of the great pandemic, 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, Vol. 43 No. 3 (Summer 2020): p56-82

Grant Peters article highlights the influenza pandemic between 1918 and 1919. This was the worst outbreak of Influenza Haskell had ever had.

[Vuckovic, Myriam], “Onward ever, backward never.” Student life and students' lives, 1884-1920. (2001)

I added this source because it was an interesting dissertation regarding all thing's student life. This source was particularly useful in that it talked about numerous ways to find history from Haskell school and where certain things were lost.

[Raymon Shmidt], “Lords of the Prairie: Haskell Indian School Football, 1919-1930 Journal of Sport History Vol. 28, No. 3 (Fall 2001): 403-426.

While Haskell had a lot of discrepancies among their students, all could agree that football was one of their greatest past times. The article highlights the success of the team between 1920 and 1930. The members of the team were said to be Haskell's finest representation of Native Americans.

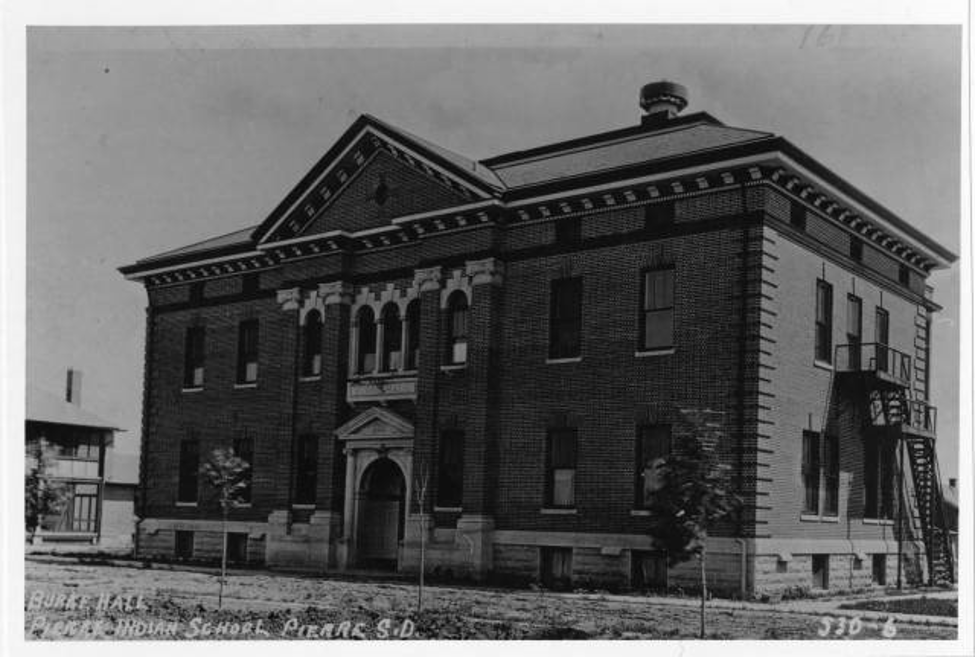

Pierre Indian School

The Pierre Indian School, which opened in 1891, was a federal boarding school located on the outskirts of South Dakota’s capital. At the junction of the Lower Brule, Crow Creek, Cheyenne River, and Rosebud Reservations, the school still stands today as the Pierre Indian Learning Center. While today the learning center serves to educate, for almost a century, it was designed to dismantle, destroy, and dilute Native American culture to the point of extinction.

The Pierre Indian School, which opened in 1891, was a federal boarding school located on the outskirts of South Dakota’s capital. At the junction of the Lower Brule, Crow Creek, Cheyenne River, and Rosebud Reservations, the school still stands today as the Pierre Indian Learning Center. While today the learning center serves to educate, for almost a century, it was designed to dismantle, destroy, and dilute Native American culture to the point of extinction.

The perpetuation of Native American mistreatment, trauma, abuse, and cultural genocide stems from the development of the Indian Boarding School System. One of the first of these boarding schools was Pierre. During the school’s 83 years under the control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, students were given lashings with open safety pins secured to wet towels, made to hold bricks with open palms until their arms gave out, forced to kneel in the name of God, under threat of his punishment, until their knees bled. The children who attended, some as young as 5 years old, left as shells of their former selves.

Through hearing from survivors, like one who was brave enough to share his story at Jenna Kunze’s talk, light has been shed on the atrocities committed by the Indian Boarding School System in the United States. The effects of this system can still be seen impacting Native communities today in the form of generational trauma, infrastructural and educational setbacks, and an overall degradation of the prevalence of Indigenous culture and language as a whole.

Sources

Regarding Modern Day Pierre Indian Learning Center -

Pierre Indian Learning Center. (n.d.). About PILC. pilc.k12.sd.us. Retrieved October 29, 2023, from https://pilc.k12.sd.us/pilc/aboutpilc/

Pierre Indian Learning Center’s “about us” page is the place to find basic information about what stands where the Pierre Indian School once was. Today, the school is called the Pierre Indian Learning Center, and it is holds classes for indigenous children from 15 different tribes across 3 states. Most of the students who go through the PILC are underprivileged, have limited access to education, are impacted by extenuating circumstances such as learning disabilities or social problems, or speak different languages. The home page briefly references the history of the Pierre Indian School in terms of land grants and how its leadership changed hands but does nothing to come to terms with the school’s dark past.

Sioux City Journal. (October 16, 1988). For PILC. Newspapers.com. Retrieved November 9, 2023, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/sioux-city-journal-for-pilc/82923486/

This article, discussing the Pierre Indian Learning Center, was published in the Sioux City Journal 14 years after the school was turned over to the Bureau of Indian Affair’s hands. In it, grievances are expressed about the school’s mishandling of complaints. Many staff members at the PILC, according to the author, were fired when their problems were brought up to their superiors, instead of simply having their issues solved. While not immensely valuable historically, this clipping helps to display information about how the mishandling and mismanagement of Indian Boarding Schools is perpetuated across generations, centuries even, despite whatever growth may have occurred overall.

Lindell, C. (2019, September 24). Presentation explores history of PILC. Capital Journal. Retrieved October 28, 2023, from https://www.capjournal.com/news/presentation-explores-history-of-pilc/article_b9a5b79c-eab7-5d6e-ba7d-b92746b981f2.html (Original work published 2007)

A local newspaper reports on the history of the PILC, and consequently the Pierre Indian School. The article, which comes from the Capital Journal, is blocked by a paywall, but gives some information as to how the Pierre community recognizes the Pierre Indian School today.

Regarding Pierre Indian School -

Hedgpeth, D. (2023, October 25). ‘12 years of hell’: Indian boarding school survivors share their stories. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/08/07/indian-boarding-school-survivors-abuse-trauma/

This gut-wrenching tale of survival and resilience is a recounting of then-6-year-old Dora Brought Plenty’s journey through the boarding school system. The Washington Post’s Dana Hedgpeth describes how the young orphan was ripped from her hometown classroom and plunged headfirst into the torture of an Indian Boarding School. The 72-year-old survivor can still remember the sight of her braids hitting the floor as they were lopped from her head, the darkness of the basement she was thrown into, half naked, awaiting a fate unknown. For almost 5 years, Brought Plenty endured beatings for speaking her language, arduous challenges for asking simple questions, and relentless degradation for nothing more than who she was. The experience left her crippled mentally, as she turned to self-harm as a coping mechanism. It wasn’t until her senior years that she finally began to find her inner peace. She now expresses her trauma through art, a common method to visualize that which often cannot be said. This source is of incredible importance for a number of reasons, the paramount of which is that it teaches how the wrongdoings of the past are perpetuated today. Dora Brought Plenty’s story, like the stories of thousands of other survivors, exposes the evils of the boarding school system to the world in defiance of the government’s silence. Without the bravery like hers to endure, schools like Pierre could have been successful in the extermination of Native culture altogether.

Brown, Brock, "Analyzing the History of Native American Education in South Dakota" (2022). Schultz-Werth Award Papers. 35.

https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/schultz-werth/35

Brock Brown’s detailed exposure of how the effects of Indian Boarding Schools still ripple to this day is jarring. In South Dakota, businesses experience heightened staff-turnover rates, students’ absences are staggering, and locations with reliable internet service are few and far between. These seemingly unprecedented and unrelated setbacks for local communities can actually, according to the author, find their source at the Pierre Indian School, and other South Dakotan boarding schools like it. Because of not just decades, but a century of abuse, mistreatment, and underfunding, Native communities have fallen behind in quality of life, education, infrastructure, and employment. The boarding school system stalled the enrichment of indigenous populations by generations, and the Pierre Indian School played a large role in kickstarting that setback.

“Indian Education Board Takes Full Control of Indian School”. Wassaja. San Francisco, CA. (August 1975). Page 4. Image Viewer - American Indian Newspapers - Adam Matthew Digital (amdigital.co.uk)

While not abundantly informative, this brief newspaper article gives some context as to what it was like when the reins of the Pierre Indian School were handed from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the Pierre Indian Board of Education in 1975. The change led to a more inclusive and beneficial education for many of the students who attended the school by offering leadership which could more closely relate to, and better understand the needs of the community as a whole in Pierre.

“Agricultural Classes at Pierre”. Indian School Journal – About Indians. (May 1915). Pages 477-478. Image Viewer - American Indian Newspapers - Adam Matthew Digital (amdigital.co.uk)

A detailed schedule of what a few weeks could have looked like for a student at Pierre is provided in this 1915 journal. Laborious and daunting, the schedule reads less like a student’s day than a farmer’s. Week after week, according to the journal, a student would have found themselves learning about anything from plowing fields, to breeding cows, to how to maintain a barn. Far from a typical education, even for the time, because students were taught about agricultural practices instead of more typical school subjects, Native people were intentionally forced into manual labor as a means of living instead of more progressive, comfortable, or high paying jobs. This subjugation of Indigenous people, the feigned equality, continually leaves the Indigenous population of the United States worse-off than had boarding schools like Pierre never been established.

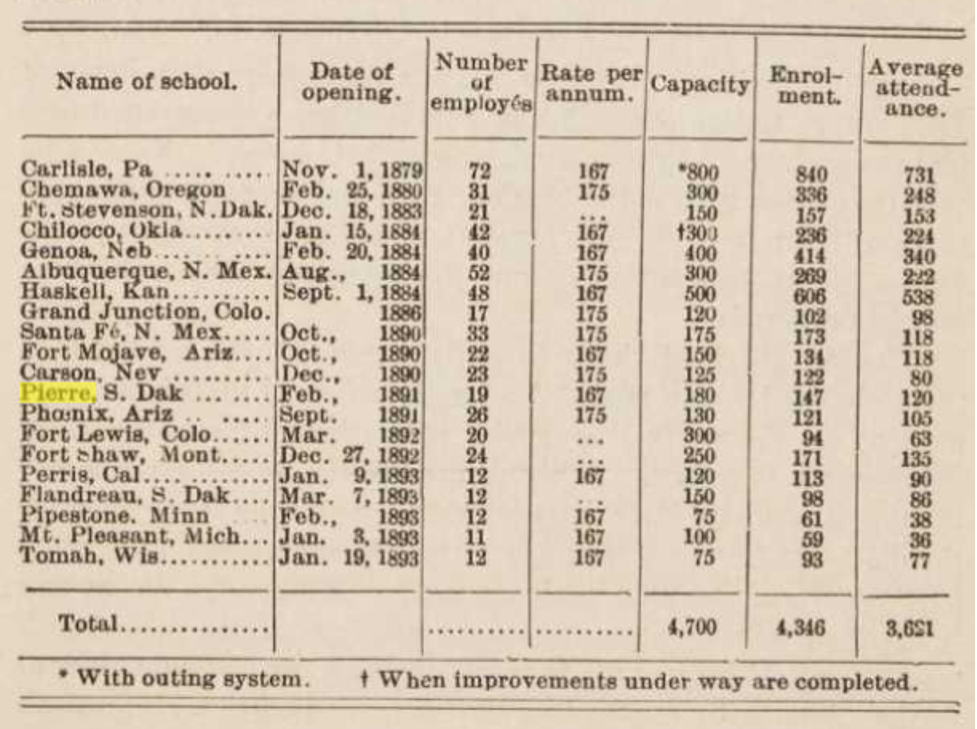

“How Shall the Indians Be Educated?”. The North American Review. (1894). Page 443. Image Viewer - American Indian Histories and Cultures - Adam Matthew Digital (amdigital.co.uk)

This snippet from an 1894 book titled “How Shall the Indians Be Educated?” gives some very useful information about what the Pierre Indian School looked like around when it first opened. The statistics about number of students and staff, opening date, average attendance and capacity helps us to visualize what the school was like more accurately. Specific numerical data paints a picture of how the students lived, and what those who founded and ran the school had in mind for said students. Without knowing the anticipated attendance, the intentions of not just Pierre, but all Indian Boarding Schools wouldn’t be laid bare as it can be today.

“Pierre Indian School Graduates 31”. The Daily Plainsman. Huron, South Dakota. (May 30, 1940). Page 3. Pierre Indian School - 1930 - Newspapers.com™

This newspaper article, published in The Daily Plainsman in May of 1930, commemorates the graduates of the Pierre Indian School. This is a necessary resource because it shows how those in power envisioned their attempt at eradicating Native language and culture as a success with each student who went through the school. The newspaper may be celebrating the achievements of the individuals, but when you look deeper, it’s not to praise their hard work or eventual achievements, but that once they graduate, they are, in the school’s eyes, “cleansed” of their nativity.

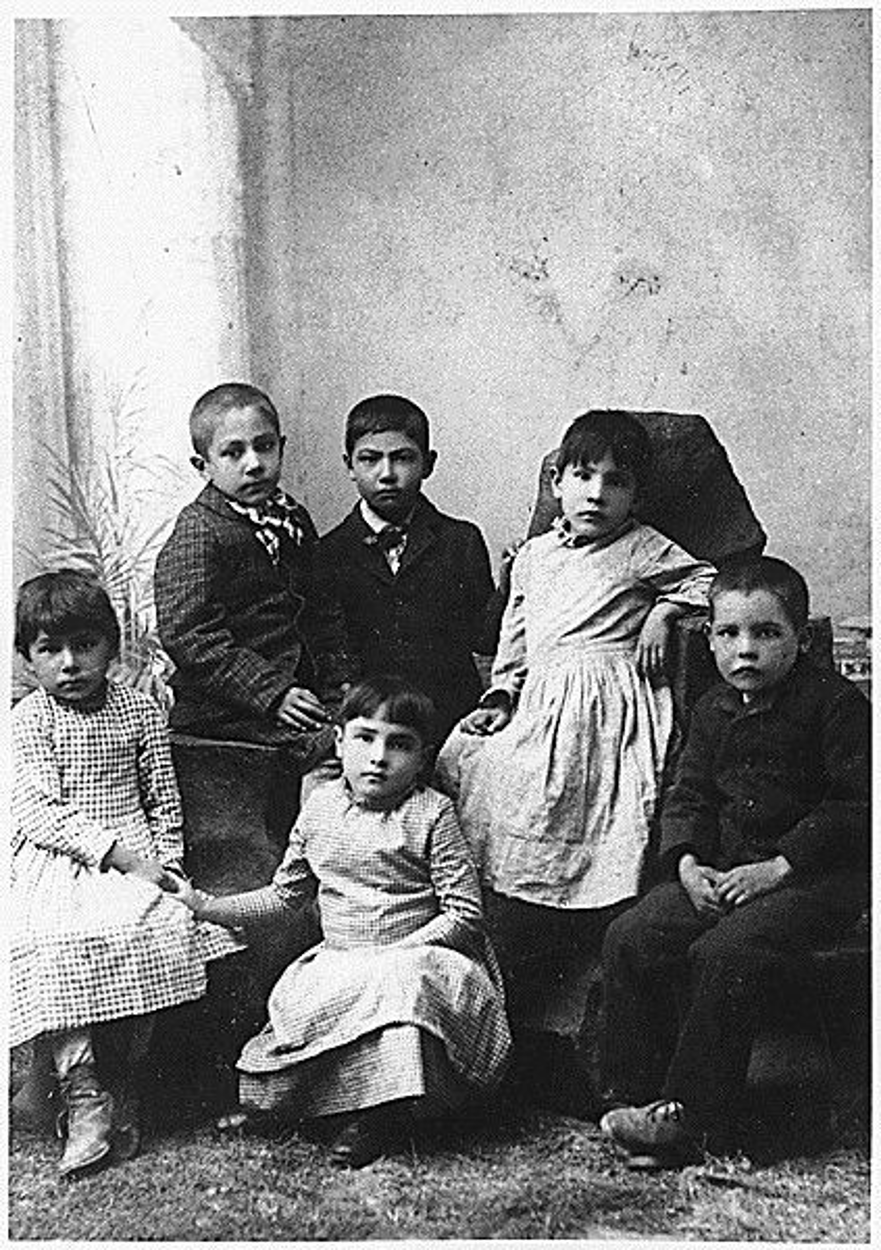

Students at Pierre Indian School; 1893; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/students-at-pierre-indian-school , November 13, 2023]

This picture is the pinnacle of the phrase “a picture says a thousand words”. The students, arranged like toys in a window, are meant to convey the killing of the Indian to save the man, but do nothing but solidify the anguish that these schools caused. You can see the fear in each of their eyes, made to pose, most likely under threats of abuse. You can see their freshly shaven heads, a reminder of their culture being stripped from them both externally and internally. Another reminder of which is their clothing. Formal and bland, their traditional attire now discarded, the students were forced to wear what made them appear as transformed from indigenous to white.

Associated Press. (2023, November 6). Survivors say trauma from abusive Native American boarding schools stretches across generations. WGVU NEWS. https://www.wgvunews.org/news/2023-11-06/survivors-say-trauma-from-abusive-native-american-boarding-schools-stretches-across-generationsn

This Associated Press article, published in November of 2023, sheds light on both the Pierre Indian School as well as the boarding school system on a broader scale. Abuse was physical, emotional, and sexual for students who attended Pierre, and as the article says, it lasted for generations. The lifelong impact from the trauma endured at Pierre Indian School was passed down from students to their children, grandchildren, and beyond.

While not exactly a source in of itself, the South Dakota Digital Archives holds many photos of the Pierre Indian School and its students both during its tenure and after.

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, 1884- 1980: A Bibliography

Prepared by Jadisha Proano

***

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, founded in 1884, was a federally operated Native American boarding school located in north-central Oklahoma, USA, near the town of Newkirk. Its establishment was part of the broader policy of assimilation and forced acculturation of Native American children. Chilocco aimed to provide vocational and agricultural education to Indigenous students from various tribal backgrounds, including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Wichita, Comanche, and Pawnee nations. The school played a significant role in disrupting traditional indigenous cultures and languages, causing lasting harm to many students. It operated for nearly a century, until its closure in 1980. After its closure, the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School property is shared in trust between the Kaw, Ponca, Otoe-Missouria, Pawnee, and Cherokee nations. The tribes have worked to reclaim and revitalize the land, aiming to heal the historical wounds inflicted by the school and promote cultural preservation and economic development in the region. The property now serves as a symbol of resilience and a testament to the strength of indigenous communities as they work towards reclaiming their cultural heritage and identity.

There exist many National Archive records on Chilocco that range from student publications to health records. There are also oral history interviews on Chilocco that were conducted by researchers Sarah Milligan and Julie Pearson-Little Thunder from Oklahoma State University. These interviews were a part of Milligan and Pearson-Little Thunder’s Chilocco Indian Agricultural School Alumni Oral History Project.

However, some National Archive documents have limited information available or might be missing information from specific years. It is also important to know that the official Chilocco Alumni Association website link does not function. A link provided on Oklahoma State University’s Chilocco Indian Agricultural School Collection to the Chiloccan, the annual yearbook for Chilocco students, is also inaccessible. The link will lead to the National Archives Catalog but will take too long and time out.

Primary Sources

National Archives, Fort Worth, Texas

Records of student publications

-

The World’s Fair Daily Indian School Journal

-

June 2-September 16, 1904. 1 vol. 1 in.

-

Arranged chronologically by date of issue

-

A daily journal published by Chilocco students under the direction of E. K. Miller during the Louisiana Purchase Exposition at St. Louis. The magazine contains notices of exhibits and programs at the fair and news of interest to the general public. Several pictures of World's Fair buildings and officials are included in the publications. NAID 1105264 5-18-1-03-4

-

The Indian School Journal

-

December 1904-26. 3 ft. (6.8 letter boxes)

-

Arranged chronologically by date of issue. Published weekly from 1904-06; monthly from 1906-26. Issues have been bound into volumes yearly from 1904-16 and 1918-21. There are unbound copies for 1917 and 1925-26. No volumes have been located for the years 1922 and 1923.

-

A magazine published by students and printed in the print shop in Chilocco. Contains articles about the Indian service and various tribes, stories, poems and inspirational paragraphs, and advertisements from various states and countries, there are numerous photographs of students, faculty, school buildings, Indian houses and artifacts, and other subjects of interest to students of ethnology. NAID 1105265 5-18-1-03-4

Records relating to students

-

Register of Pupils

-

1884-1908. 1 ft. (7 vols.)

-

Arranged chronologically by year of attendance. Each volume contains an index arranged alphabetically by first letter of pupil's surname. The volume for 1901-02 is arranged alphabetically by surname of pupils. There are no records for 1892, 1893, 1899, 1900, or 1905.

-

Bound volumes of handwritten lists of pupils. From 1884-98 the record indicates the pupil's Indian name, English name, agency, nation (tribe), band, father's name and rank, whether father and mother are living or dead, physical description, date of arrival, length of contract for schooling, and remarks. Beginning in 1901, information usually includes name, age, tribe, degree of blood, name and address of parent, date entered, and expiration date of term of schooling. NAID 1105394 5-44-1-06-3

-

Register of Pupils by Tribe.

-

1902-03. 1 in. (1 vol.)

-

Arranged alphabetically by name of tribe and thereunder by sex. There is no index.

-

Handwritten lists of pupils from over forty tribes. Only the pupils' names and occasionally a date are given. NAID 1105450 5-44-1-06-3

-

Student Case Files

-

1912-1980. 240 ft., 7 in. (662 letter boxes)

-

Arranged alphabetically by surname of student. A database of the student case files is available.

-

Folders of original, unbound records relating to individual pupils. Many files contain enrollment applications, recommendations, physicians' certificates, aptitude profiles, transcripts of grades, attendance records, and correspondence relating to travel, vacation, money, discipline, transcripts, and employment. Information usually includes date of birth, names of parents or guardians, residence, religious preference, degree of Indian blood, and tribe. Some folders contain photographs of the students and newspaper clippings. Information about many students attending Chilocco before 1912 was collected and filed with records current in 1912. No earlier case files have been located. Student applications are restricted for privacy reasons for seventy-five years from the dates of the records under the Freedom of Information Act (5 USC 552, exception b6). NAID 1105462 5-18-1-03-6

-

Index to Former Students

-

Ca 1902- Ca 1919. 3 ft. (3 index)

-

Arranged by category of boys or girls and thereunder alphabetically by surname of the former student.

-

Index on 3" x 5" cards of former Chilocco students. The information given on most cards includes the student's name, tribe, degree of Indian blood, age, sex, and the dates that the student entered and left Chilocco School. Some of the cards only give information about the address of a former student who had entered military service. NAID 2514841 5-29-1-16-5

Records Relating to Health

-

Physicians’ Reports

-

1903-36. 1 in.

-

Arranged by date of report (incomplete).

-

Copies of various reports by school physicians and other personnel related to medical facilities and treatment. Reports include a Quarterly Sanitary Report of Sick and Injured, 1903, by Wm. T. McKay, physician; a semi-annual report in 1910 by W.T. McKay; a semi-annual report dated 1918 by Andrew Pearson, M.D.; a report on "Health Activities at Chilocco" including twelve snapshots of students during a milk drinking campaign by principal Rey F. Heagy (undated); a one-page annual report dated 1926 by Dr. D.P. Gillespie; two-page monthly reports of Domiciliary Patient and Out Patient files in May and June of 1936 by Dr. H. N. Sisco. For other records related to the hospital and student health see entry 8. NAID 1105222 5-18-1-03-4

-

Dispensary Out-Patient Records

-

1919. 3 in.

-

Arranged in groups by month of visit.

-

Original 4" x 6" cards with a record of patient visiting school dispensary. Information given in name, tribe, diagnosis, address, age sex, degree of blood, symptoms, whether vaccinated for smallpox or typhoid, whether transferred to hospital, sanatorium or school and dates of treatment. Patients seem to have come from various schools for treatment. NAID 1105253 5-18-1-03-4

-

Records of Dr. H.V. Hailman Relating to Trachoma

-

1924-25. 1 in.

-

Arranged roughly chronologically by date of letter.

-

Correspondence and other materials relating to the work of Special Physician Hubert V. Hailman who was an Indian Service appointee assigned to special work among Oklahoma Indians in treatment of trachoma. The prevalence of the disease is indicated by the treatment of over 400 pupils at Chilocco School, Sapulpa, and other places where Dr. Hailman conducted clinics. Materials include circulars, correspondence with Oklahoma physicians, weekly narrative health reports, lists of supplies and medicines, and lists of pupils treated at Chilocco and Cantonment, Oklahoma. NAID 1105257 5-18-1-03-4

Chilocco Alumni Association

The link to the official Chilocco Alumni Association website is inaccessible.

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School Photographs

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School Oral History Project, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma

The Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, located in north central Oklahoma, operated from 1884 -1980 as one of a handful of federal off-reservation Indian boarding schools in the United States. Thousands of students passed through the school's iconic entryway arch during its nearly century-long existence. Even today, Chilocco continues to be a powerful site for memory for its remaining alumni from over 127 tribes, as well as the Native peoples, directly or indirectly impacted by its history and scholars and students throughout the world who seek to understand its role within the larger context of U.S. Indian boarding schools. This oral history project features over 40 oral history interviews conducted with the school's alumni and military veterans. The oral interviews are available in both video and transcript format. There exists a YouTube playlist of these interviews under the Oklahoma Oral History Research Program channel, as well as transcripts in Oklahoma State University’s Digital Collections.

Chilocco History Project Research File, Oklahoma Oral History Research Program Digital Project

The Chilocco History Project Research File presents a comprehensive list of links that mention or are about Chilocco Indian Agricultural School. Unveiling archival documents, interviews, and historical accounts, the project sheds light on the experiences, challenges, and triumphs of individuals associated with Chilocco. The Chilocco History Project Research File serves as a valuable resource, preserving the narratives and contributing to a deeper understanding of the experiences of students who attended Chilocco throughout its 100 years of existence.

“Chilocco Indian Agricultural School” entry, Oklahoma Encyclopedia of History and Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society

Oklahoma Indian School Magazine Collection, Oklahoma Digital Prairie, Oklahoma Department of Libraries

Oklahoma Digital Prairie provides visitors with unique digital content spanning more than 100 years of rich, vibrant history from the 46th State. The resource areas found here include documents, photographs, newspapers, reports, pamphlets, posters, maps and audio/visual content. Content ranges from the late 1800s to the present day. Some collections are solely attributed to the work of librarians, archivists and content managers at the Oklahoma Department of Libraries. Others, such as the collections providing citizens access to digitized state government publications and forms, are joint projects between ODL, the Office of Management and Enterprise Services, and the individual state agencies contributing publications and documents.

The Chiloccan, National Archives Catalog

The link to the National Archives Catalog is inaccessible.

Herrera, Allison, "Chilocco Indian Agricultural School Should Remain a ‘Site of Conscience’", Newsy

This article provides an exploration of the complex legacy surrounding the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School. The piece investigates the recent discovery of numerous graves of Native children who attended the school, prompting a broader examination of the history of boarding schools in Canada. Authored by a team of journalists, the narrative unfolds through interviews with caretakers Jim and Charmain Baker, alumni, and books written by authors such as K. Tsianina Lomawaima. The article covers the abandonment of the cemetery by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1980, the dedicated efforts of caretakers to identify those buried in unmarked graves, and the federal policy of assimilation that shaped the school's early years. The incorporation of personal narratives, historical documentation, and the perspectives of key figures involved in the preservation of Chilocco adds depth to this comprehensive examination. The dichotomy of the school's history is explored, from its challenging beginnings to positive transformations in later years. The article closes by addressing the current state of Chilocco, its neglected buildings, and the aspirations of alumni to transform the school into a cultural center. As a valuable resource for understanding the nuanced history of Chilocco, this article is a critical addition to the discourse on Native American boarding schools.

Meriam Report: The Problem of Indian Administration (1928)

The Meriam Report, officially titled "The Problem of Indian Administration," is a seminal document in Native American policy and governance. Commissioned by the Secretary of the Interior in 1928, this landmark report was prepared by Lewis Meriam and his team of experts. The comprehensive study critically evaluated the conditions of Native American reservations and schools, revealing systemic issues such as poverty, inadequate healthcare, and substandard education. The Meriam Report played a pivotal role in reshaping federal policies toward Native Americans, influencing subsequent legislative reforms. Its meticulous analysis and recommendations remain foundational in understanding the historical challenges faced by Indigenous communities in the United States. This blurb acknowledges the Meriam Report as a cornerstone in the examination of Native American affairs and policymaking.

Secondary Sources

K. Tsianina Lomawaima. (1994). They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School. University of Nebraska Press.

Established in 1884 and operative for nearly a century, the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma was one of a series of off-reservation boarding schools intended to assimilate American Indian children into mainstream American life. Critics have characterized the schools as destroyers of Indian communities and cultures, but the reality that K. Tsianina Lomawaima discloses was much more complex. Lomawaima allows the Chilocco students to speak for themselves. In recollections juxtaposed against the official records of racist ideology and repressive practice, students from the 1920s and 1930s recall their loneliness and demoralization but also remember with pride the love and mutual support binding them together—the forging of new pan-Indian identities and reinforcement of old tribal ones.

Julie Pearson-Little Thunder; Johnnie Diacon; Jerry Bennett. (2022). Chilocco Indian School: A Generational Story. Oklahoma State University Library, Chilocco History Project. https://chilocco.library.okstate.edu/items/show/3867

Jaya, a Native teen temporarily separated from her mom, accompanies her grandmother and Aunt to a family reunion. Between chores and activities, the older women lead her through a story about Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, combining history and their own memories of attending the boarding school in northern Oklahoma. Their account arouses a range of emotions in the teen, from tears, to laughter, to anger, to compassion. The result: a new respect for her family and the resilience of Native peoples, along with insights into how Jaya might handle the changes in her own life. This story, set in present-day Oklahoma, was compiled from the experiences of real students who attended Chilocco, and their recollections were shared through oral history interviews, photographs, letters, and other archival sources. It engages students and adults in an often-overlooked part of U.S. history and pushes back against stereotypes of Native identity.

Theses and dissertations

Koenig, Pamela. “Chilocco Indian Boarding School: tool for assimilation, home for Indian youth.” M.A. diss., Oklahoma State University, 1992

Flandreau Indian Boarding School

Flandreau Indian Boarding School: A Bibliography

By: Mia Chapman

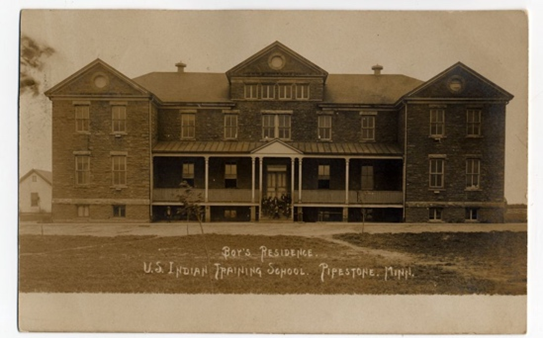

Main Building of the Flandreau Indian Boarding School, 1893

Books

Child, B. J. (1998). Boarding school seasons American Indian families, 1900-1940. University of Nebraska Press.

“Boarding School Seasons" delves into the emotional history of Indian boarding school experiences in the first half of the 20th century. Focused on Haskell Institute in Kansas and the Flandreau School in South Dakota, the book unveils the impact through letters from parents, children, and school officials. The correspondence reveals the profound effects on entire families, as children grappled with homesickness while parents faced loneliness. The letters highlight concerns about the well-being and academic progress of the children, clashes over living conditions, and strategies to navigate restrictive visitation rules. Despite threatening family intimacy through the suppression of traditional languages and cultural practices, families turned to boarding schools for relief during the Depression when economic challenges became more pressing than the threats posed by these institutions. "Boarding School Seasons" offers a nuanced exploration of the aspirations and struggles of real people during this complex historical period.

Landrum, C. L. (2019). The Dakota Sioux Experience at Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools. UNP - Nebraska. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvb1htgs

Cynthia Leanne Landrum's work, "The Dakota Sioux Experience at Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools," explores the relationship between the Dakota Sioux community and the Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools. It sheds light on how Dakota Sioux students perceived these boarding schools to an end and community institutions, paralleling the approach of some Eastern Woodland nations to non-Native education during the 17th and 18th centuries. Landrum offers a fresh perspective on the Dakota people's acceptance of this education system, providing insight into their evolving relationships and the historical dynamics that emerged with the alliances between Algonquian Confederations and European powers.

Articles/Journals

Child, B. (1996). Runaway Boys, Resistant Girls: Rebellion at Flandreau and Haskell, 1900-1940. Journal of American Indian Education, 35(3), 49-57. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24398296?sid=primo&seq=6

Abstract from “Runaway Boys, Resistant Girls: Rebellion at Flandreau and Haskell, 1900-1940. Journal of American Indian Education, 35 (3), 49-57.

Rebellion was a common feature of government boarding school life during the period from 1900 to 1940. Boarding schools imposed stringent regulations regarding home visits and running away allowed students and families to circumvent the harsh system. Letters written by students and family members reveal factors that motivated students to run away, the different forms rebellion took, and the strong emotional history of the boarding school experience. Letters show that rebellion evoked anger and frustration in administrators, anguish and worry in parents, and demonstrate the considerable humor, resilience and resourcefulness of boarding school students.

Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe to seek return of historic land base. (1994). Ojibwe News (Bemidji, Minn. : 1996), 6(23). https://www.proquest.com/docview/368253137?pq

Abstract from “Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe to seek return of historic land base. (1994). Ojibwe News (Bemidji, Minn. : 1996), 6(23).”

"The Flandreau Santee Sioux Council is going to aggressively pursue the dream long held by previous chairman and Councils - the return of our historic land base", stated Chairman [Chuck Allen], newly elected Tribal Chairman of the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe." By this action, the Tribe is preparing not only our future, by the future needs of other Tribes historically served by the school. Off reservation to effectively educate the diversity of students currently attending these schools. We must do more than simply "warehousing children", Chairman Allen stated in a council meeting where Resolution 94-113, seeking the return of the land and title to the facilities currently occupied by the Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school, was passed by the FSST Council.

Ellingson, Bill. 2021. “A History of the Flandreau Indian School.” South Dakota Public Broadcasting. https://www.sdpb.org/blogs/images-of-the-past/a-history-of-the-flandreau-indian-school/.

The following text is from a two-part article written by Bill Ellingson, a member of the Moody County Historical Society. The articles were first published in 2020 in the "Moody County Pioneer," the Moody County Historical Society's quarterly newsletter.

Established in the late 19th century, the Flandreau Indian School (FIS) in the United States has a rich history. Originally a mission school, it transitioned to a government day school until 1892-1893. Dr. Charles Eastman, a respected American Indian, attended FIS. The push for a federal Indian boarding school gained momentum in 1889, and by 1892, the first school buildings were completed. Initially focused on vocational training, FIS evolved into an accredited four-year high school, offering diverse academic programs. Despite enrollment fluctuations and occasional closure attempts, the school remains operational, with recent enrollment stabilizing around 320 students. The campus comprises thirteen buildings and employs approximately eighty-five staff members across various departments.

Archival Collections

Record Group 75: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Flandreau School and Agency. National Archives, Kansas City, https://www.archives.gov/kansas-city/finding-aids/html/rg75-flandreau-school-and-agency-series-title-list

-

All records are offline.

US Senate. Committee on Indian Affairs. Proposed Space and Privacy Requirements on the Flandreau Indian School. 99th Cong. 2nd Sess. February 10, 1986.

Hearing in Flandreau South Dakota to review the impact on Flandreau Indian Boarding School of BIA proposed privacy requirements for BIA- operated schools.

South Dakota State Archives. Flandreau Agency. Superintendent’s Annual Narrative and Statistical Reports from Field Jurisdictions of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1910- 1935

The National Archives regional records center in Kansas City, Missouri, is the repository for these records. As part of the Indian Archives Project, the South Dakota State Archives funded the microfilming of these records, enhancing accessibility for tribal members in South Dakota. The records encompass various categories, including the principal's subject correspondence files, general correspondence, superintendent's correspondence, employee records, attendance registers and reports, monthly reports, heirship testimony and reports, enrollment registers, school census records, reports of arrivals and departures of students, records of pupils in school, roster of parents and guardians, and church affiliation of pupils.

Newspapers

Kaufman, B. (1995). Flandreau Council asks for investigation of basketball coach: Students seek removal of head coach. Indian Country Today (Oneida, N.Y.), 15(24). https://www.proquest.com/docview/362590533?pq-origsite=primo&accountid=10506

Abstract from “Indian Country Today (Oneida, N.Y.), 15(24)”

"There was no abuse," Flandreau Superintendent Jack Belkham told Indian Country Today. "We investigated the incident and found there was no abuse, and we dropped the case.

"You're trying to make a mountain out of a molehill," Mr. Belkham said. "We have investigated this incident. We have determined that there was no abuse. You're just going to have to take my word on this."

"For a lot of these kids," the athletic director said, "Flandreau is a last chance."

Fort Mojave Indian School

Fort Mojave Indian School Annotated Bibliography

Adacus Greene

The Fort Mojave Indian School was a boarding school founded on August 22, 1890. It was located at Fort Mojave, and was named the Herbert Welsh Institute from 1891 to 1892. McCowan, the superintendent of the school when it opened, focused mostly on a vocational education, as the boarding school lacked funding and he needed food and clothes for the students there. The Fort Mojave Indian School opened to other tribes in 1924, but would close in 1931 after the policy on Indigenous education shifted back to teaching on reservation schools.

The records of the Fort Mojave Indian School are very thin and does not have as much information on the school. Most records of the school are found to be between 1924 to 1931, which was when the school opened to non-Mojave students. The University of Las Vegas has a large collection of information on the Fort Mojave Indian School, and it is mostly online, while the National Archives records in Riverside, most of it is not online and must be seen in person.

Newspaper Sources

"August 8, 1926 (Page 50 of 64)." Pittsburgh Gazette Times (1925-1927), Aug 08, 1926, pp. 50. ProQuest, https://dickinson.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-8-1926-page-50-64/docview/1856469559/se-2.

This newspaper article on the Pittsburgh Gazette Times talks about how girls from the Sherman Institute and the Fort Mojave Indian School are being taken to Hollywood to see sets of countries around the world.

"ITEMS FOR ARIZONA." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Dec 13, 1899, pp. 3. ProQuest, https://dickinson.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/items-arizona/docview/163939125/se-2.

This small article is about bids for installing the water and sewer systems for Fort Mojave Indian School, 9 years after the school opened.

"Los Angeles County: Cities and Suburban Places.: UNUSUAL CHARGE AGAINST A PASADENA PREACHER. REPORTED TO HAVE POISONED TWO HUNDRED BIRDS. Humane Society Appoints Committee to Investigate--Elks make Merry on Exalted Ruler's Birthday--City Council Settles Dispute Over Car Tracks. ELKS MAKE MERRY. TRACKS CROSS ALLEY. SCHOOL OF FORESTRY. COSTLY STREET WORK. FORT MOJAVE SCHOOL. LITTLE ONES." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Aug 05, 1903, pp. 1. ProQuest, https://dickinson.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/los-angeles-county-cities-suburban-places/docview/164213122/se-2.

This article talks about the head teacher at the school taking a trip back to Fort Mojave after a summer of learning. This gives important statistics on the number of students, and specifically the number of boys, at the school in 1903.

"Fayth B. Wilson." Navajo Times, Aug 17, 2006, pp. 1. ProQuest, https://dickinson.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/fayth-b-wilson/docview/225297175/se-2.

This article by the Navajo Times is about Fayth B. Wilson, a former student of the Fort Mojave Indian School who passed at 92 in 2006. After going to the Fort Mojave Indian School, and later the Sherman Indian School, she graduated with the third nursing class of 1936, and was the first registered nurse from her tribe.

National Archives at Riverside, California

(Descriptions are from the National Archives)

“This series contains correspondence of superintendent, August F. Duclos. Subjects include the management of accounts, including individual Indian accounts, purchases, personnel, the outing of students to the Riverside and Los Angeles, California areas.”

“This series includes a set of printed forms (5-366) documenting many of the school's buildings, located at Fort Mojave in Arizona. The form records the type of Indian Service floor plans used, building numbers and use, capacity, dimensions, cost and date of construction, cost of repairs, materials used, types of heating and lighting systems, building condition, estimated value, and information about water and sewer facilities and cost of repairs made. The card includes a photograph of the building.”

“This series consists of several forms: Applications (form 5-192a), Record of Pupil in School (form 5-186), Pupil's Dental Record (5-243b), Report Card (form 5-247) and Vocational Record Card (form 5-297). Subjects included on vocational record cards include dairying, farm implements, farm crops, carpentry, and painting for boys and cooking, poultry raising, laundering, and sewing for girls.”

“This series consists of correspondence, reports, financial records, personnel and student records. The bulk of these records are related to the students and employees at the Indian School. Also included is correspondence with off-reservation boarding schools, including the Sherman Institute and Phoenix Indian School, and others.”

Congressional Archives

United States. Survey of Conditions of the Indians in the United States. Washington, U.S. G.P.O. HeinOnline, https://heinonline-org.dickinson.idm.oclc.org/HOL/P?h=hein.amindian/surcopu0017&i=811.

In this congressional hearing, the superintendent testified in front of congress to talk about the closure of the school, and what will happen to the students there, more specifically the Navajo students who study at Fort Mojave.

University of Las Vegas

“Fort Mojave Indian School Records (MS-00034).” UNLV Special Collections and Archives, special.library.unlv.edu/ark:/62930/f1988p. Accessed 2 Oct. 2023.

“The Fort Mojave Indian School records (1890-1923) consist of two bound books of correspondence, finance, and administrative records, pump station blueprints, and policy implementation and fact-finding records.”

Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School

Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School, 1893-1934: A Bibliography

Prepared by Demi Gerovasilis

***

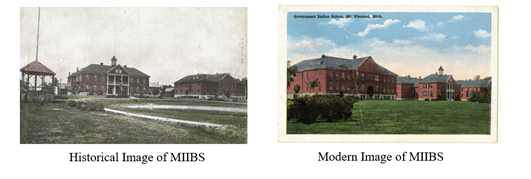

The Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School (MIIBS) was the third boarding school in the state of Michigan, in which its establishment was carried out by an act of Congress in 1891. Natives from the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, including the Chippewa of Saginaw, Swan Creek, and Black River on the Isabella Reservation were primarily brought to this school. Specifically, Anishinabe Three Fires Confederacy lands were taken, and in exchange, government officials assured that they would provide an education to all Indian children. However, assimilation forcibly occurred at this institution; children could not preserve their identity, culture, and language, and they were additionally required to wear uniforms and cut their hair. In fact, Warren Petoskey, an Odawa and Lakotah elder, who writes about past American Indian boarding schools, directly states that many parents would sing their children's deaths songs as they were taken away to Mt. Pleasant, knowing that even if they survived, "they would never be the same again."

With an average enrollment of 300 students per year, upon arrival, Native children were disinfected with alcohol, kerosene, or DDT and were given new English names to work, both educational and manual labor. They were further told that their original language was the “devil’s tongue.” Students were between the ranges of 5-14 years old; however, photographs reveal that some may have been younger or older than this range.

This institution included approximately a dozen buildings over 320 acres and while girls learned and practiced “domestic science” in a modern cottage powered by steam and electricity, boys labored the school’s extensive farm, specializing in “fruit culture.” The various classes, manual labors, sports teams, such as baseball and football, and religious teachings implemented at MIIBS were primarily intended to make Native Americans more civilized and “American.”

The poor conditions that occurred at this institution, including overcrowding, limited food rations, and a lack of sanitation ultimately led to disease outbreaks, such as such as smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, flu, and tuberculosis. While official documents only record five deaths at this school, local tribe members and researchers currently believe there were over 200 deaths at MIIBS. Although the boarding school closed in 1934, it remained open until 2009 as a home and training institute for those with disabilities. Specifically, the former boarding school became reestablished as the Mount Pleasant State Home and Training School for the Developmentally Disabled. Yet, with the closing of this school, remaining students were sent to the Tomah Indian Industrial School in Wisconsin or to local public schools.

After 2009, the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe signed an agreement with the federal government to purchase the land and remaining structures as an effort to study, preserve, and restore MIIBS. In addition, the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe aims to promote public education about federal industrial boarding schools and continuously celebrates the anniversary of the closing of the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding school through the annual event, known as, Honoring, Healing & Remembering. This specific event along with other gatherings across Michigan offer an opportunity to honor the children who lost their lives at these boarding schools. Overall, the prominent goal of current tribal efforts is to bring the native community together, so that the recognition, healing, and preservation of their cultures and traditions may be valued and respected.

University Collections:

Elizalde, Tere. “Mt. Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School.” Indian Boarding Schools in Michigan. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://umsi580.lsait.lsa.umich.edu/s/indian-boarding-schools-in-michigan/page/mt-pleasant-school.

This source serves as a digital archive organized by the University of Michigan, which focuses on boarding schools in Michigan. Specifically, insight into the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School is provided. A timeline of the Indian Boarding Schools in Michigan is displayed, which offers a newspaper article detailing the parade and ceremony that was held once the first stone was laid for the construction of the MIIBS.

The newspaper clipping from the Isabella County Enterprise highlights the events of this parade was, “The Stone is Laid: With Imposing Ceremonies: And a Grand Parade” (Isabella County Enterprise, 1892, pp.1, 5, 8), which is provided by this university source:

This source also offers a copy of the original Mt. Pleasant School for Indians pamphlet from 1913, emphasizing the school’s aim to prepare Natives for the “Duties, Privileges, and Responsibilities of American citizenship.” Also, in this pamphlet contains descriptions and photographs of the building facilities and grounds, Native Americans’ classes and activities.

Mt. Pleasant Indian School Annual Reports from 1910−1913 are included in this source, which offers insight to the yearly updates, industries, purchases, student enrollment, employees, and educational/extracurricular details about the school. The reports further denote the various illnesses occurring at the school each year. MIIBS Annual Reports 1910–1913 addressed to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

Finally, the item for the public memo titled Honoring, Healing, and Remembering 2021, from the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan is provided; this event honors the 225 lives lost to the Mt. Pleasant Industrial Indian Boarding School, occurring every year, on June 6th, since 1934.

Books, Articles, and Journals

Leverage, Megan. “The Mt. Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School.” American Religion, June 28, 2023. https://www.american-religion.org/empty-places/mtpleasant.

The American Religion journal includes an issue on the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School. An overview and summary of this boarding school’s history and advancements over time are explained. The author, Megan Leverage, is a lecturer at the Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, MI, where she teaches Religion, Race and Discrimination in America, Religion and Social Issues, and Death & Dying.

This source provides an image which includes a “No Trespassing,” since the property is now owned and respected by the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe (currently, the past boarding school and remaining buildings are not open to the public):

A quote by Ronald Ekdahl, the chief of the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan is also included in this issue, which states, “the purpose of this school ... was to kill the Indian and save the man; to teach us a ‘better’ way of life; to erase our culture; to erase our language; to take away all those values that we as Anishinabe people are able to celebrate today as in direct opposition to that.”

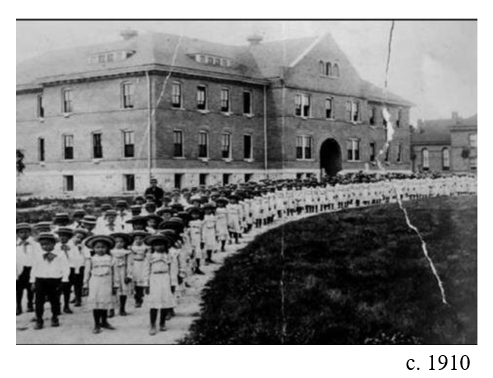

Furthermore, a photograph of enrolled boys and girls in uniforms and lined up in front of MIIBS is given:

Mount Pleasant Indian Boarding School Pt. 2

In particular, the prayers that boarding school children had to recite each day is included (pg. 10):

Morning Prayer:

"Now I get me up to work,

I pray Thee Lord, I may not shirk;

If I should die before tonight,

I pray Thee Lord, my work's all right."

Evening Prayer:

"Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray Thee Lord, my soul to keep;

If I should die before I wake,

I pray Thee Lord, my soul to take."

Also, a letter written by Eliza Silas to her mother on June 1, 1920 is provided, in addition to an appeal letter written by a mother, Mrs. Annie Turner, for the return of her daughter, on April 22, 1919 (pg. 11). It should be noted that a 1918 photograph of Mabel Turner, age 7, who was the daughter of Mrs. Annie Turner is further included (pg. 14).

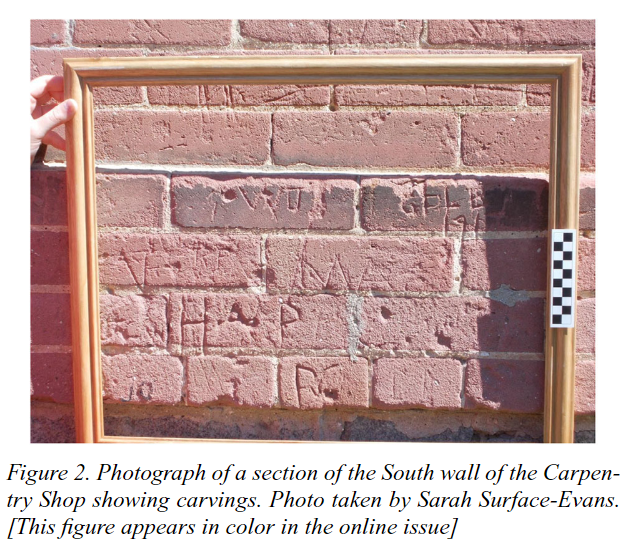

Surface-Evans, Sarah L. “A Landscape of Assimilation and Resistance: The Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 20, no. 3 (2016): 574–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26174310.

The research conducted in this journal evaluates the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School via the use of archival, archaeological and oral history evidence. The landscape and material records collected from this former boarding school depict the acts of resistance that Native students demonstrated toward this institution. Specifically, in her 2016 archaeological survey, anthropologist Sarah Surface-Evans excavated numerous buttons at the site of the school, explaining that the students would use buttons as a form of currency among themselves. These children would discreetly remove buttons from their clothing and use them to participate in powwow and pipe ceremonies or trade them with each other (Figure 6). This small gesture is just one example of students’ resistance; these buttons served as an invisible sociopolitical purpose of creating kinship networks, imitating/representing the traditions of Anishinabe beadwork and wampum of Eastern Woodlands tribes.

Brewer, Graham Lee. “Indian Boarding School Investigation Faces Hurdles in Missing Records, Legal Questions.” NBCNews.com, July 15, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/indian-boarding-school-investigation-faces-hurdles-missing-records-legal-questions-n1273996

This news article details investigations that are underway in relation to Indian boarding schools and the efforts that are currently being carried out by the Department of the Interior to bring justice and healing to the cultural assimilation faced by various tribes over generations. Specifically, the author, Graham Lee Brewer is a national reporter for NBC News and a member of the Cherokee Nation, based in Norman, Oklahoma. In this article, he explains that while the U.S. documented a total of five deaths of Indigenous children at the Mount Pleasant school, once the land was returned to the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan in 2010 by the state, the tribe’s researchers found records validating the deaths of 227 children. Furthermore, Shannon O'Loughlin, chief executive of the Association on American Indian Affairs and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation, emphasizes that “The hard part is investigating the land and understanding what that boarding school did.” It is essential to acknowledge that the Native children of Mount Pleasant are remembered nearby at the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways, where researchers have continued to document the stories of survivors and the federal policies which intended to whitewash their identity. This news article also includes imbedded videos and images to provide additional context to federal government’s campaign to destroy the cultural identity of Indigenous children across numerous boarding schools in the U.S. and Canada.

Graham, Lester. “Saginaw Chippewa Tribe Honors Children Who Died after U.S. Forced Them into Boarding School.” Michigan Radio − Michigan’s NPR News Leader, July 19, 2021. https://www.michiganradio.org/families-community/2021-06-04/saginaw-chippewa-tribe-honors-children-who-died-after-u-s-forced-them-into-boarding-school

This article focuses on the current acts of the Saginaw Chippewa tribe in their hopes to honor the children who attended The Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School. In the present day, the Saginaw Chippewa tribe owns the remaining complex, and a ceremony, known as the “Honoring, Healing, and Remembering,” is held at the neighboring Ziibiwing Center Anishinabe Culture and Lifeways every year. Particularly, this event is shared online annually, and includes prayers, ceremonial drum songs, dedications, and a history lesson. The heart of this ceremony is the reading of the 227 children’s names with sentimental drum beats to honor and remember each student.

Tribal Cultural Centers

“Respecting the Site of the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School.” Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan Homepage, September 16, 2020. http://www.sagchip.org/news.aspx?newsid=3219.

The official website for the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe provides relevant information regarding the history and evolution of Mount Pleasant boarding school over time. In fact, a historical timeline of MIIBS from 1856 to 2022 is provided, which associates specific dates to information, updates, and advancements of this boarding school.

MIIBS Timeline:

Furthermore, it provides external documents, press releases, and extensive details regarding the former Mount Pleasant boarding school. It should be noted that the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe additionally operates the Ziibiwing Cultural Society (the tribal museum), and encourages the teachings, “honoring, healing, and remembering” of the Native children and their experiences at this industrial boarding school. With that said, it should be indicated that every year since 2009, the annual “Honoring, Healing & Remembering” event brings attention to the injustices experienced by Native children who attended MIIBS.

Archival Collections:

National Archives, Chicago*

National Archives and Records Administration, Chicago Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency, 1892 to 1934 Mount Pleasant, Michigan

**Descriptions of these records are copied from the Mt. Pleasant Indian School and Agency Finding Aid as provided via email by the National Archives at Chicago. Additional information regarding each of the Administrative, Financial, and Health and Welfare Records, can be obtained through email request to chicago.archives@nara.gov.

-

Administrative Records

-

Abstracts of Property, January 7, 1917 to July 1, 1917, (National Archives Identifier 117692773).

-

Administrative Records of the Superintendent, 1915 to 1933, (National Archives Identifier 111794183). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “Topics include curriculum and instruction, school personnel, hospital and health, the transportation of students, land and heirship matters regarding the families of school children, student activities such as band and athletics, alumni activities, applications from parents of children from outside of Michigan or in some instances Canada, and enrollment surveys and statistics of Indians enrolled in public schools. Some correspondence appears, consisting mainly of letters to and from former students, (arranged by initial letter of surname), and correspondence with H. B. Peairs, Chief Supervisor of Education of the Office of Indian Affairs.”

-

Administrative Records of the Superintendent Relating to Purchase of Supplies and Equipment, 1919 to 1926, (National Archives Identifier 112063710).

-

Annual Reports, 1923 to 1926, (National Archives Identifier 112063697).

-

Applications for Enrollment, 1921 to 1933, (National Archives Identifier 112063698).

-

Applications for Positions, 1925 to 1926, (National Archives Identifier 117678295).

-

Correspondence with Office of Indian Affairs, 1918 to 1926, (National Archives Identifier 111794130).

-

Correspondence with Other Indian Agencies and Schools, 1917 to 1926, (National Archives Identifier 111794163).

-

Circular Letters, 1915 to 1944, (National Archives Identifier 112541064).

-

Decimal Correspondence Files, 1926 to 1946, (National Archives Identifier 111653168). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of incoming and outgoing correspondence of the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency and its successor the Tomah Indian Industrial School. Subjects include education, health, finance, purchasing, and general administrative matters.”

-

Press Copies of Letters Sent to the Department, 1904 to 1906, (National Archives Identifier 117692774).

-

Employee Time Books, 1926 to 1932, (National Archives Identifier 112063709).

-

History of the Mount Pleasant Indian School, April 6,1892 to June 6, 1934, (National Archives Identifier 112063699). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of a single journal kept by the Superintendent of the Mount Pleasant School to occasionally record daily events which occurred at the Mount Pleasant Indian School. Entries created include the first day of class, new buildings opening, graduation ceremony notes, agricultural events, and entries for when the school closed.”

-

Press Copies of Miscellaneous Letters Sent, 1904 to 1910, (National Archives Identifier 111794178).

-

Records of Employees, 1892 to 1923, (National Archives Identifier 112063708).

-

**Records of Pupils in School, 1929 to 1933**, (National Archives Identifier 112063707).

-

Records Related to the Closure of the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency, 1933 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 113313397).

-

Register of Pupils, 1893 to 1932, (National Archives Identifier 112063700).

-

**Student Case Files, 1893 to 1946, (National Archives Identifier 623671). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of student case files of Indians who attended Mount Pleasant Indian School in Mount Pleasant, Michigan. Files typically include the student's application to attend Mount Pleasant, as well as reports of grades, deportment, and medical or disciplinary problems.” A majority of “the files include the student's name, date of birth, tribal affiliation, degree of Indian blood, home address and dates of attendance.”

-

Financial Records

-

Account Book of the Employee’s Club, 1905 to 1914, (National Archives Identifier 117090838).

-

Accounts Current Report, Jun 1930 to Aug 1932, (National Archives Identifier 117678294).

-

Accounts Payable Voucher File, 1918 to 1932, (National Archives Identifier 34922629).

-

Analyzed Liabilities and Vouchered Expenditures, 1916 to 1917, (National Archives Identifier 112396060).

-

Appropriation Ledgers, 1907 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 112396058).

-

Bills of Lading, 1932 to 1934 (National Archives Identifier 34922740).

-

Cash Accounts Ledger, 1917 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 112396068).

-

Check Register, 1924 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 112396067).

-

Coal Receipts, 1927 to 1933, (National Archives Identifier 113345672).

-

Cost Ledgers, 1920 to 1925, (National Archives Identifier 112346296).

-

Encumbrances and Journal Vouchers, 1926 to 1933, (National Archives Identifier 113313407). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of registers and correspondence concerning the setting aside of funds (an encumbrance) for different responsibilities at the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency. Encumbrances contain appropriation number and title, purpose, voucher number, date, amount, and balance. Journal vouchers contain several types of forms including "Notice of Transportation," "Allotment of Funds," " Request for Allotment," "Journal Voucher (Miscellaneous)," and "Report of the Deposit of Funds to the Credit of the United States."”

-

Miscellaneous Account Books, 1927 to 1932, (National Archives Identifier 112541065).

-

Payroll Records, 1906 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 34923175). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series contains records of payroll expenditures by the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency, which was in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and primarily worked with the Ojibwa (or Chippewa) of Saginaw, Swan Creek, and Black River on the Isabella Reservation. The first subseries comprises Cash Payroll of Employee form N-330, and contains a list of all employees paid during that pay period, including position, time employed, rate of pay, amount pay, and remarks. The second subseries consists of the Record of Positions and Salaries form, which includes the name, position, race (Indian or white), and line entries for each month of employment containing rate of pay or salary, amount paid, deductions and other related information.”

-

Records of Supplies Purchased, 1923 to 1931, (National Archives Identifier 112264827).

-

Registers of Financial Transactions, 1919 to 1932, (National Archives Identifier 112346284).

-

Requisitions for Stores, 1932 to 1933, (National Archives Identifier 113313408). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of requests (Form 5-720) for various items from the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency storehouse. The requisitions have entries for name of the items requested, column to denote it was delivered and the unit cost and a total requisition amount for each line item. The date delivered, the initials of the storekeeper and the signature of the requisitioner are included. While many of the requests appear to be from the Kitchen, other departments include, Boys, Girls, Hospital, Dining Room, Home Economics, Physician, Engineer, Carpenter Shop, and the Vocational Department. Items requested are common food stuff, leather straps, medicine, laundry soap, shoe polish, and sporting equipment.”

-

Trust Responsibilities

-

Individual Indian Check Register, 1929 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 112541067). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of a record of activities in the accounts of Indians at the Mount Pleasant Indian School. Entries list deposits or withdrawals from the account, dates, names of parties involved in the action, and the amounts.”

Mount Pleasant Indian Boarding School Pt. 3

-

Health and Welfare

-

Hospital Census Records, 1931 to 1933, (National Archives Identifier 117692772). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of a series of Weekly Census Report (Form 5-351) and Weekly In-Patient and Dispensary Patient Report of Hospital (Form 5-348a) used at the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency Hospital. Included in the reports are the numbers of patients seen, type of care when admitted (obstetric, tubercular, or others), tests and vaccinations given, disposition of cases, and related information. Names of patients do not appear. Occasionally, the numbers and type of staff on duty will appear.”

-

**Record of Patients, 1926 to 1934, (National Archives Identifier 112541066). Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of lists of patients' diagnoses, and treatment for mainly students at the Mount Pleasant Indian School. An entry was established for each patient, listing name, age, sex, diagnosis, data related to treatment, and occasional remarks. This series requires screening prior to release.”

-

**School Social Worker Files, 1932 to 1945, (National Archives Identifier 112541075).** Quoted from the Chicago Record Group 75 Finding Aid: “This series consists of correspondence, reports, and records kept by social workers of the Mount Pleasant Indian School and Agency. Correspondence, both incoming and outgoing, is mostly with officials of the Office of Indian Affairs, other public agencies such as local courts and welfare offices, and other schools. Reports include those of the social worker pertaining to performance of duties and general conditions of Indian families, and from surrounding counties relating to Indians placed in public schools. Other records relate with automobile and transportation, copies of directives and bulletins, and published articles about school.”

-

*Register of Pupils, 1893 to 1932* (National Archives Identifier 112063700) is digitized and available in the National Archives Catalog. The microfilm publication number is M1996 (1 Roll). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/229037296

**Some of these records may be restricted due to personal privacy concerns**

In addition, microfilm series M1011, Superintendents Annual Narrative and Statistical Report from Field Jurisdictions of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1907 to 1938. M1101, Roll 89 contains information for the Mt. Pleasant School, 1908 to 1933. This microfilm series is online through the National Archives Catalog Roll 89 Mount Pleasant Indian School, 1910 to 1933, (Michigan) https://catalog.archives.gov/id/155948222

-

Student case files identified on Chicago’s National Archives web page for Mt. Pleasant:

-

An additional series of online resources provided by the National Archives at Chicago:

Additional Articles and Newspapers:

“Mt. Pleasant Center’s History.” The Morning Sun, June 17, 2021. https://www.themorningsun.com/2008/07/01/mt-pleasant-centers-history/.

The Morning Sun newspaper is a leading publication based in Mount Pleasant, Michigan, which serves as the primary source of local news and information. This article explains the history of Mt. Pleasant specifically in regard to its transition from a federal boarding school to a facility for those with developmental disabilities and mental illness. It is first explained that in 1933 the MIIBS was transferred to the state of Michigan for $1. After this transition, the boarding school was shut down and The Michigan Home and Training School was established in 1934. This training school was a vocational institution for boys who were “mildly mentally retarded or borderline intelligent,” according to a document from the Mt. Pleasant Center. The conversion from the federal boarding institution to the boys’ training school took less than one year; in fact, when the first group of patients from Lapeer, which was another mental institution, were brought to the training school, some Native children were still living there. These Native children were orphans and had no place to go. In 1946, the institution was changed to the MT. Pleasant State Home and Training School, and in 1975, the school was renamed again to the Center for Human Development. In 1995, the name was changed to The Mt. Pleasant Center, which remained a facility for those with developmental disabilities, until the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe signed an agreement with the federal government in 2009 to purchase the property; the tribe’s efforts to respect and restore MIIBS history continues today.

Field, Sue Knickerbocker. “Ceremony to Honor Native Boarding School Children.” The Morning Sun, June 1, 2023. https://www.themorningsun.com/2023/06/01/ceremony-to-honor-native-boarding-school-children/.

The author of this news article, Sue Knickerbocker Field, initially explains the story of Martha Shagonaby, who was a former student of MIIBS. Martha Shagonaby personally did not want to give up her language, customs, culture, or family at this institution, thus in 1899, she set fire to the school’s main building, destroying it. Although Martha remained a prominent and well-respected figure, standing up for Native children’s mistreatment at the time, the institution was rebuilt a year later. Sue Knickerbocker Field further states “That fire didn’t kill anyone, but deaths at the boarding school were not uncommon.” Unfortunately, MIIBS continued to operate until 1934, and even though it has been 89 years since its closure, and intergenerational trauma persists, Therefore, to honor Native children and specifically MIIBS, the author explains that the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe hosts “the annual Honoring, Healing and Remembering event Tuesday from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. with a sunrise ceremony, guest speakers and student roll call to pay tribute to their suffering, strength and resilience.” This event starts with the sunrise service at 7 a.m. at Mission Creek Cemetery; the day includes grand entry and flag song, opening prayer, a pipe ceremony, the student eagle staff dedication, guided tours of the boarding school, keynote addresses, and welcomes from Tribal Chief Theresa Jackson, Central Michigan University President Robert Davies, and Mt. Pleasant Mayor Amy Perschbacher. Currently “the MIIBS Committee is working toward developing the boarding school buildings and grounds to become a place for healing, education, wellness and empowerment on a local, national and global level.”

Surface-Evans, S.L. and Jones, S.J. (2020), 8 Discourses of the Haunted: An Intersubjective Approach to Archaeology at the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 31: 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1111/apaa.12131