Tales of Technology

From slide rules to calculators, film to digital cameras, typewriters and word processers to modern computers and iGadgets, alumni recount memories of how technology has changed during their lives and the impact technology has had on the college and the wider world.

I have fond memories of Nancy Hays James ’61 and me turning on the radio late at night—the only time we could get reception from New York City’s station, WOR. It was a rare opportunity to listen to classical music. Our favorite was Handel’s Water Music. I also remember the new “modern” hair dryer some of the girls used. It was a motorized contraption that blew warm air through a hose to a large drawstring cap that fit over the hair. I won’t send the photo I have of my roomie, Lois Mecum Page ’61, ensconced in one of those monstrosities.

—Toni Aaron Greenfeld ’61

Silver Spring, Md.

SWYM, short for Say What You Mean, my Shakespeare professor’s favorite acronym, was a mystery to me.

I said what I thought I meant on corrasable [bond] paper given to smudges and typed on my mother’s 1925 Olympia typewriter that she had used at Dickinson 25 years before me. Black, rough textured, square, lighter and taller than later models, this particular typewriter occupied the middle of four different desks in my four different dormitory rooms in my four years at Dickinson. It was most often used in the middle of the night before a deadline. These rough, yet final, drafts of my typical 20-page essays were, no doubt, a bit chatty and meandering. In addition to an essay comparing Plutarch’s rendition of Julius Caesar to Shakespeare’s, I remember essays on Tom Brown’s Schooldays, imagery in Sappho’s poetry, treatment of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth through centuries of literature and a case study of a child I called Tommy Tortoise, who dropped out of a Carlisle kindergarten partway through the semester.

During my later typewriter years, paper smudges morphed into liquid paper cross-outs followed by retyped words that often had a raised, dark veneer. Meanwhile, my teaching career required mass production with correct typing on ink through stencil for mimeos or on ditto paper that left students sniffing alcohol traces and me wiping purple fingers.

Eventually I graduated from a rather heavy but fancy IBM Selectric II with its own correction ribbon and font wheels to a Macintosh SE, on the market for only three years, with its square floppy disks that I finally discarded with reluctance. Recently, I took my PowerPC G4, a dinosaur in its own right, to the Apple store where a “Genius” said, “Hmm, this is the second one of these I’ve seen today.” I took it as a compliment.

Now I wonder how today’s word processors influence their users’ mind processes. Do I write drafts on legal pads because Word is a dictator? Kindle wants me to store my original documents in Amazon Cloud. What does Cloud vaporize into? Was my professor’s SWYM actually a forerunner to texting?

My granddaughter, a first year at Dickinson, e-mails from her laptop, “My writing is getting better.” I wonder how she knows this. I need to ask her sometime.

—Katharine Everhart Paull ’62

Kagel Canyon, Calif.

I taught fourth grade at Kahala Elementary School in Honolulu for 17 years. Fortunately for me, Kahala was a school with smart kids and wealthy parents. I didn’t know anything about computers (it was 1987), and the parents held fundraisers to hire a computer teacher and maintain a state-of-the-art lab stocked with Apple II computers, which I recall were quite bulky. I always sat next to the slowest kid, who would feel pretty smart when I asked for help. This child, like many, didn’t know how to do long division yet, but she was a computer wiz.

A year later, when I finally got a vague idea of what the kids were learning, those computers were replaced by tiny boxes called Macs. It was at that point that the focus was on teaching keyboarding (a fancy name for what my generation called typing), and the students started “word processing” (a fancy name for writing) on the computers.

I always had the students compose their writing with pencil and paper. After I corrected their work, I had them type it on the word processer and save it. Then I would sit down with them individually and have them look at their writing on the screen. I used the cut-and-paste mechanism to show how they could move sentences and paragraphs around. Then I would print out a copy of the reorganized writing and give it to them to use their pens to add more details. They would go back to the computer and retype what they wrote. Since we only had one computer in the classroom, this was time-consuming but effective.

I just turned 68. I’m retired from teaching and use Facebook to connect with my family and friends from high school, college and the Marine Corps. I’ve also been able to Skype with family after my youngest son set up an account so that I could chat with my daughters and grandchildren on the East Coast. If it wasn’t for my sons (my youngest is a junior at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn., and currently studying abroad at Oxford University in England), I’d probably still be using my 1965 Corona portable typewriter.

—Robert Mumper ’65

Kailua, Hawaii

We in the old Office of Communications & Development (C&D) began to watch the approaching digital storm in the mid-1990s, but the price for a Nikon digital camera, which was about the size of a Webster’s dictionary (remember dictionaries?), was $10,000 or so. So we just waited.

In February 2001, Olympus came out with a reasonably priced camera that actually looked like it was designed as a camera rather than a computer accessory, so we went with that. Just one year later, Nikon introduced the D100, and we found ourselves on the slippery slope. For a few years I shot everything with two or three cameras: black-and-white film, color print film and digital, and I still did the campus shots on slide film. But by 2005, it was all over for film, and not just at Dickinson.

I attended a workshop in Maine in August 2005 that was taught by Bob Krist, a very well-known travel photographer and father of Brian Krist ’06. At the beginning of each workshop, the participants gathered for introductions, and in 2004, Bob asked how many were shooting film and how many digital. Ten hands went up for film, two for digital. “OK,” said Bob. “We can handle that.” One year later, he asked the same question of our group. Ten hands went up for digital, and two for film. Bob looked like a deer caught in the headlights. “I gotta call my wife!” “Why?” we asked. Turned out the Maine Photographic Workshops had only a few digital projectors, and all the classes would have to share. So Bob called his wife and had her send his own equipment. He described the one-year flip-flop as a “digital tsunami.” It overtook us all, not the least Kodak itself, now on the ropes. I haven’t shot a roll of film since fall 2005.

—A. Pierce Bounds ’71

Carlisle, Pa.

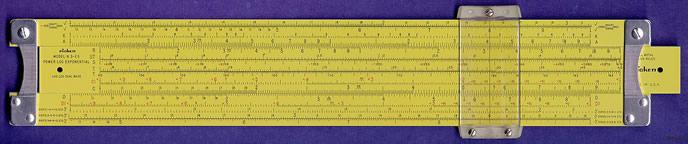

I was in the last class of first-year physics (fall 1974) that required a slide rule … and in fact, the professor eschewed calculators as an unfair advantage. The slide rule at least taught me viscerally what logarithms really are. Some fellow students—the math and physics folks—even had nifty belt cradles for their slide rules, something like today’s cellphone holders. Alas, I did not.

—David J. Horn ’74

Atlanta, Ga.

This contraption, known as the Ride Board, was located in the basement of Dickinson’s Holland Union Building. It allowed classmates looking for a ride and someone offering a ride to connect. Did it ever go online? This proof picture, taken around 1972, was faded and foggy even back then. Thanks for the opportunity to share what might be considered to have been an early simulation of the Internet.

—Oren Kaplan ’74

Kiryat Bialik, Israel

I had Professor [Richard] Sia for physics and a very cool Pickett slide rule that did trigonometric calculations. I really liked the visual and analog nature of the slide rule. There was an art to accuracy.

—Howard Newstadt ’74

Unionville, Pa.

My daughter always said she wanted to live in a house in the rural town just up the road from us. Visions of stopping by for a chat or to play with future grandchildren danced in my head. After college, she left for graduate school in Arizona, met husband David and ended up in a small town in northern California. It’s great to visit, but not exactly around the corner, and there’s no popping in to take a small grandchild off of weary hands.

When our first grandchild was born, I wondered how we would ever be close to her. I have to say, four years later, we are the closest of companions—with only a handful of transcontinental trips between us. How could this be? A little-known miracle called Skype. A free, downloadable software app, Skype allows for free video conferencing between users with a webcam. It’s that simple.

An article in The New York Times a few years back, “Grandma’s on the Computer Screen,” confirmed that I wasn’t the only one skyping with a toddler. According to the article, the AARP estimates that nearly half of all American grandparents live more than 200 miles from at least one of their grandchildren, and a sociologist at the University of Southern California says that about two-thirds of grandchildren see one set of grandparents only a few times a year, if that. Who would’ve guessed that two of the unlikeliest demographic groups not particularly known for being high-tech, grandparents and toddlers, would be among Skype’s earliest adopters.

After skyping most days of her first year, clapping and cheering for her every accomplishment, I was so afraid she would be frightened by my real-life appearance, right out of the computer screen, for my trip out for her first birthday. As soon as she saw me, she outstretched both arms to reach for me. Success! Not the strange apparition I had feared, but a familiar face and beloved friend.

Michio Kaku, in his fascinating book Physics of the Future: How Science will Shape Human Destiny and our Daily Lives by the Year 2100 describes the world our grandchildren will inhabit as seamlessly integrated with technology—nano, robotic, AI, virtual reality, you name it. I can see that already, with my young granddaughter who loves texting us from her mom’s cell phone and who looks forward each Sunday at 11 a.m. to her virtual playdate with her grandparents.

—Jackie Leff Spritzer ’76

Lawrenceville, N.J.

When I came to Dickinson in the fall of 1972, people spoke of “the computer,” since there was only one on campus: an IBM 1130 that occupied a room on the first floor of South College. This computer served both student and administrative functions for the campus. The CPU was built into a large desk that, along with the various large peripheral devices, took up most of the room. There was no remote way to access the computer.

I was able to get a job as a student computer consultant right away, even though those positions usually did not go to first-year students. This was due to my having experience working with that model computer on a chess program with a friend attending Elizabethtown College.

The way you got information into the computer was via stacks of punch cards that were created on keypunch machines located in another room. You received your output from a large, expensive “line printer” that could print only one font. The only graphics you could do were by printing out various patterns of letters. You could create “music” by placing an AM radio in various locations and picking up the signals generated by the circuitry. This required a lot of tinkering to figure out the radio placement and program steps needed to generate various sounds. While you could in theory interact with the computer with a keyboard and typewriter-style printer located on the CPU desk, this was rarely done as it tied up the system, which was not powerful enough to multitask. Although modern computers have a million or more times the speed and memory of the 1130, it did force you to write efficient code. Otherwise you could never fit your program into memory.

The 1130 was replaced with a Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC) PDP-11 computer in 1976. There was also a computer made by Interdata that was somewhat of a flop before the PDP was purchased. The PDP was the first system to have widespread remote access on campus. It was replaced by a DEC VAX computer and later by a DEC Alpha model, which was finally phased out about four years ago. The terminals were at first mostly teletype-style printing units connected via slow telephone modems. Later CRT display terminals became common until replaced with personal computers in the mid-1980s.

One of the first common personal computers found in quantity on campus was the DEC Rainbow, many of which were purchased in 1984. Later various Macintosh models and PC clones were popular in labs and offices.

—Tom Smith ’76

Carlisle, Pa.

My parents’ high-school graduation present to me was a newfangled state-of-the-art electric typewriter with automatic type correction, and it was such a beauty I often shared it with my friends and floor-mates all four years of college. It came in its own hard case the size of a large airline carry-on, and if you took it on a flight today you’d probably have to pay $200 for all the extra weight. It was a monster. But did we ever crank out research papers, essays and short stories on that baby! You could type about 20 or 30 words and they’d show up on this little screen, and then the typewriter keys would blast ’em out like a delayed reaction, which we found very entertaining. And if you made a typo, the typewriter had a built-in eraser ribbon so you could actually erase your mistakes via the keyboard, negating any need for Wite-Out.

I also remember the computer center in the basement of Bosler Hall my senior year. It was only open during certain evening hours, and you had to sign up in advance for computer time. The terminals were all wired into a mainframe that was hooked up to dot-matrix printers that chugged and beeped as your papers were printed (and then you had to tear apart the perforated pages). There was even some kind of MS-DOS-based program that enabled you to engage in some prehistoric form of instant messaging. I’ll never forget typing real-time to a boyfriend who was on a computer in a different building and thinking how high-tech that was.

My last memory is of the hall phones in all the dormitories. I’m pretty sure they were touchtone dials, not rotary, but they had an old fashioned—and loud—double ring when calls came in, and the entire floor shared the one phone. It wasn’t cordless either, so you had to sit in the little phone cubicle to have a conversation (so much for privacy).

Ah, the good old days.

—Melissa Biggar ’87

Chatham, N.J.

In 1982 when I was 12 and in sixth grade, I received my very first calculator. I truly thought this was the most advanced technology on the planet, with its “sin” and “cos” (which I still do not understand), and that no one would probably invent anything more advanced than this.

Now at almost 42, as I use my phone to text and take pictures of my family and friends, my iPad to skype, and I write this note on my laptop, I realize I have no comprehension of what will be invented to make the life of my 6-year-old son easier when he is 42. But I can’t wait!

—Artrese Morrison ’92

Point Richmond, Calif.

Published April 3, 2012