Dickinson College Student-Faculty Research Takes Aim at Billion-Dollar Farm Pest

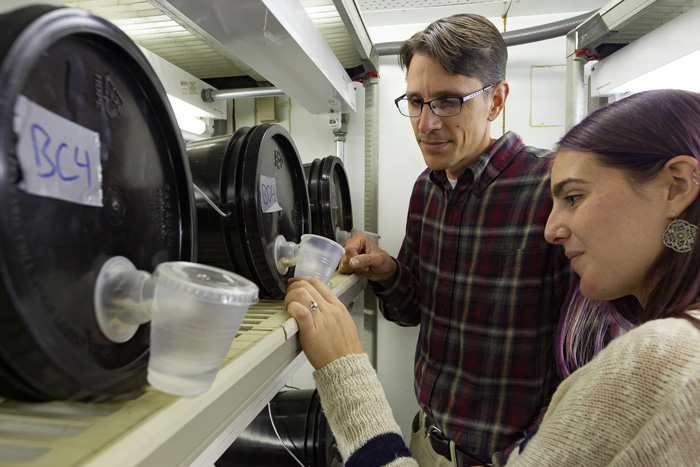

Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology Jason Smith and Kayla Simpson ’18 are out of the field and into the lab with their yearlong research project. Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

The Billion-Dollar Question

by Tony Moore

You’d probably never guess, but something as simple as a horn fly costs American farmers nearly a billion dollars each year. Here’s the big problem: They’re in constant contact with cattle, feeding on the animals’ blood up to 30 times a day. This stresses the cows, reduces feeding efficiency, can lead to infections and causes cows to grow at a slower rate.

In short, horn flies are a serious concern for cattle farmers.

Making compromises

Beginning in the summer of 2017, Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology Jason Smith and Kayla Simpson ’18 (biology), assisted by Amy Sparer ’18 (biology) and Ilana Zeitzer ’19 (biology, art & art history), took on a research project at Dickinson’s College Farm examining common approaches to controlling the horn fly population. And the project added an important component: keeping the health of the surrounding ecology in mind.

Through a Center for Sustainability Education research grant, the team looked at IGRs—insect growth regulators—selective pesticides that mimic different types of insect hormones and target specific systems.

“When you're using pesticides, usually you're making compromises,” says Smith, who notes that despite how targeted IGRs are, it should come as no surprise to anyone that pesticides kill more than just the target. “But what's really important as managers of an ecosystem is that you know what compromises you're making and you avoid the more severe ones and aim for the best possible solution.”

The team studied—in the literature and in the field—methoprene and diflubenzuron, commonly available feed-through chemicals that cattle eat and then excrete via dung, where horn flies develop as larvae.

“We found very few studies that were looking at conditions in the field and at chemical doses similar to what companies are selling,” says Simpson. “And very few studies were looking at what their impact is on other insects in the ecosystem.” Specifically under the microscope was the chemicals’ effect on dung beetles, flies and parasitoid wasps, all of which play important roles in agro-ecosystems like the one at the farm.

Results are in

Now that the results are in, Smith and his students report that neither of these chemicals are doing great things to the other insects: methoprene hurt the dung beetles, while diflubenzuron knocked out wasps and affected some fly families. And both overall hurt biodiversity—an impact expected to reduce the ecosystem’s ability to recycle valuable nutrients and limit harmful pest populations.

“What's really valuable about this research is it's going to help people know what the compromises are, and then farmers can make more informed decisions,” says Smith, whose team notified the farm staff that they recommended not using either chemical on the farm’s 18 acres of animal pastures.

“A lot of the studies we looked at said these chemicals were fine to use, so we were surprised by the results,” says Simpson, who recently defended her thesis on the topic at her honors presentation. “And we were a little sad that we didn't have a solution.”

Simpson and Zeitzer presented the findings at the Pennsylvania Environmental Research Consortium, Dickinson’s All-Science Symposium and the Society of Women Environmental Professionals, while Sparer presented at Lehigh Valley Ecology and Evolution Symposium.

This is Simpson’s fourth research project at Dickinson—after studying frogs and toads with Professor of Biology Scott Boback and elephants in Tanzania. And while most people might not associate the kind of research Simpson has done with a small liberal-arts college, Simpson knew from the start that Dickinson was the right place for a biology major.

“I knew I wanted to do research and be a biology major, and I was looking at small liberal-arts colleges,” she says. “My friends and family were like, ‘Are you sure? Shouldn't you be looking at research universities?’ I'm so glad I didn't listen to any of them. It's been fantastic, and I don't think if I had gone elsewhere I would have had these same opportunities.”

TAKE THE NEXT STEPS

Published May 9, 2018