How Do You Say ‘Ash Cloud’ in Russian?

Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

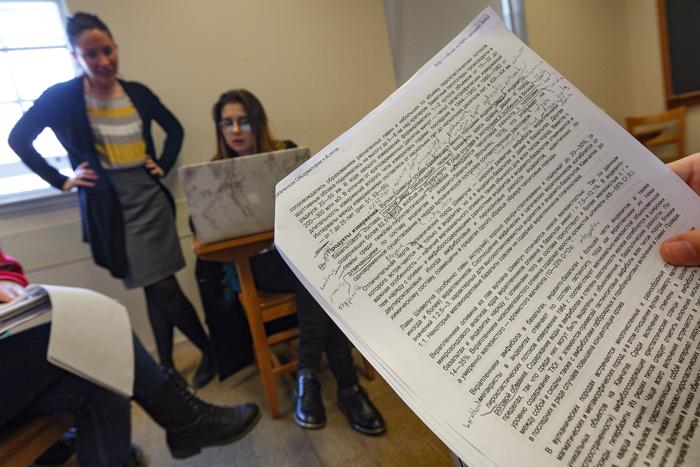

Students translate vital volcanic activity data for senior seminar

by Tony Moore

Volcanic eruptions might result in anything from delayed flights to canceled vacations to—in the most extreme cases—scores of casualties (such as when Indonesia’s Mount Tambora erupted in 1815, taking 92,000 lives, the most on record). The problem for much of the earth sciences community, though, is that volcanoes often are located in parts of the world where English isn’t spoken, so vital information might only be disseminated in English via spotty online translation services.

But underway at Dickinson is a project to translate one such region’s volcanic activity information into English, as Russian majors monitor the Klyuchi Volcanology Observatory website, which tracks the status of four active volcanoes on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East.

A useful approach

“It’s definitely a challenge, because I don’t know any of the volcano terminology,” says Allison Stroyan '18 (Russian, mathematics), a sophomore in a class usually reserved for seniors. “But it’s really enjoyable knowing we’re translating something that will be very useful to people.”

The project is part of Assistant Professor of Russian Alyssa DeBlasio’s senior seminar, Workshop in Translation. Through direct contact with Russian-speaking volcanologists, students are helping non-Russian-speaking scientists, pilots and other interested parties stay up-to-date on the seismic activity of one of the world’s most volcanically active areas.

“It’s pretty scientific, but I think it’s good to do texts like this because it shows students that as long as they learn about the subject matter, they can translate any text,” DeBlasio says. “It’s just about learning the terminology and about the field in which you’re working.”

A different animal

The possibility of a cross-disciplinary undertaking such as this first grabbed DeBlasio’s attention in 2012, when Associate Professor of Earth Sciences Ben Edwards traveled to Russia to explore the region’s volcanoes.

“When Ben came back, he told us he had all this material on amazing research being done, but it was only in Russian,” DeBlasio says. “And the only way it’s getting out there is through Google translate, which only gets about 20 percent of the work done.”

Since then, Edwards has treated DeBlasio’s students to a sort of Volcanoes 101 primer, introducing students to the Kamchatka region, his research in that area and the terminology. He’s also on hand to check the final versions of the translations, making sure the English-language product reads like something coming from a veteran volcanologist.

“It’s different from literary translation because with that you’re trying to convey the author’s voice,” says Stroyan, who has been studying the Russian language since 8th grade and will next translate the subtitles for the Russian documentary Protsess (Process). “And if you’re reading something literary, it’s more open to interpretation and can be more about your own writing style. This [technical translation] is more specific, and it’s a different animal entirely.”

Learn more

Published May 5, 2016