World Enough and Time

Opera-in-progress plumbs a landmark invention and the eccentric mind behind it

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

Fresh from a victory in a coastal French town, the British navy fleet was tossing about in a weeklong storm. When the weather cleared, would the navigators be able to regain their bearings and steer the fleet home? It was a dire situation in 1707, when celestial navigation was the best known way to chart a course, and it ended disastrously: All but one navigator figured incorrectly, and the fleet lost four warships. Once ashore, the story goes, the admiral was murdered by a woman who coveted his flashy emerald ring.

That catastrophe spurred a major scientific discovery, revolutionizing the way seafarers travel the globe. And it sets a dramatic scene for an opera-in-progress about the outsider genius who brought that discovery to the world.

Created by Professor of Music Robert Pound and Professor of English Carol Ann Johnston, World Enough and Time tells the tale of John Harrison, a carpenter, clockmaker and musician extraordinaire who developed his own musical scale (he tuned his town’s church bells and wrote choral music based on that new key). Harrison also was the son of a surveyor who shared his father’s talent for advanced mathematics, and he posited that one could figure out a ship’s exact location by measuring the time in its current place against the time at the place where it had set sail. With a clock—a marine chronometer—that could keep perfect time at sea, no view of the night sky was needed.

The problem? Harrison was a science lone wolf and a terrible communicator, with garbled speech and jumbled explanations. Even when he produced his chronometer—precise in humidity, choppy seas and extreme heat and cold—the science establishment shut him out. A political storm brewed.

Pound learned about Harrison through an audiobook of the award-winning Longitude, by Dava Sobel, which he listened to while traveling throughout the West. A noted composer who has received major commissions and wrote his Juilliard dissertation on text setting, Pound knew that the story would translate well to opera, and once back in Carlisle, he discussed it with Johnston.

As an amateur musician with dramaturg experience, Johnston was interested in music and theatre, and as a poet and expert in 17th-century literature—which is steeped in the science of the day—she connected with the subject. Last spring, while both she and Pound were, coincidentally, on sabbatical, they got to work.

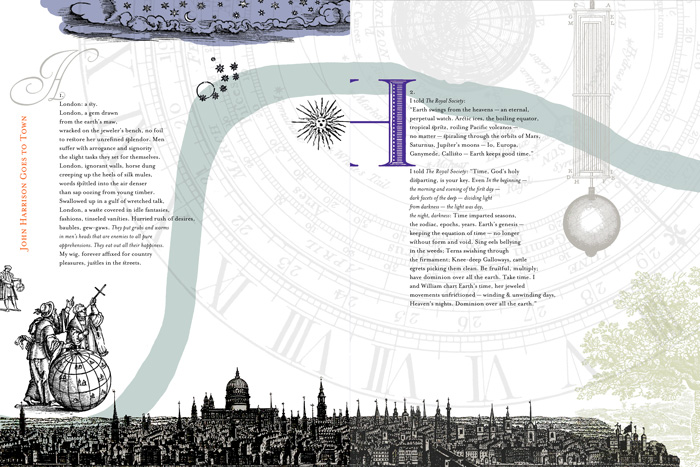

Johnston steeped herself in the era by reading 17th-century literature and source material, including books on lapidary science (to discover the significance of the admiral’s emerald ring) and travelogues by British sea captains. She and Pound then mapped out the opera in 12 acts, one for each hour on the clock. Johnston has written texts to two key scenes thus far, and Pound has set them to music.

An interarts preview

Visiting Instructor in Voice Jonathan Hays, a baritone, and pianist Craig Ketter will perform excerpts of the ongoing work during an April 5 performance at Franklin & Marshall College, an event that ties in with that college’s ongoing museum series on the sea. Pound has tapped Johnston to play the part of the woman who kills the admiral for his ring.

The performance also includes a showing of broadsides based on Johnston’s text and created by visual artist Anne Connell, whose work is grounded in Renaissance painting. The art was printed, via hand press, by Kseniya Thomas ’01.

For Pound, who regularly composes new musical works, the project is a welcome opportunity to collaborate with a colleague on a grand scale. Johnston is relishing the new task of writing dialogue for music and stage, and in a 17th-century voice. There’s also the singular challenge of writing text that is true to the protagonist’s communication challenges, while still conveying his genius.

Both enjoy the intersection of artistic forms—story and dialogue, acting, music and vocal music, and set and costume design. “That interdisciplinary aspect of opera is a big part of what makes this project so very rewarding to me,” says Johnston, who felt similarly while working on the production of a Seamus Heaney play in the 1990s. “It’s all coming together in a wonderful way.”

Learn more

Published April 4, 2016