One Spectacular Lie, Many Scientific Truths

In wake of forgery scandal, lecture examines Galileo’s scientific imagery in context of his times

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

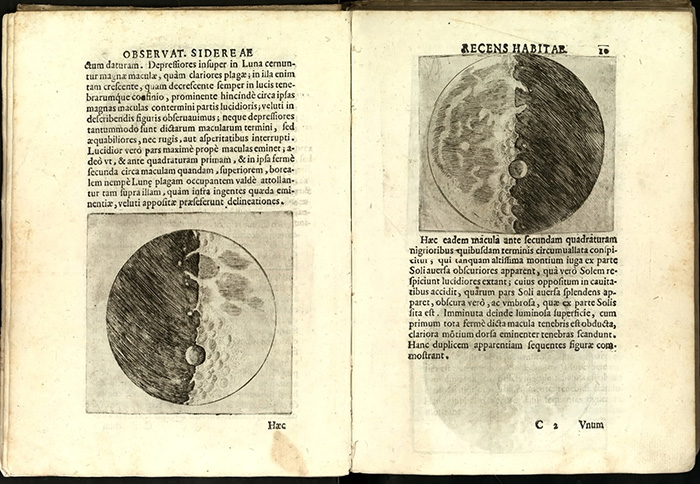

Galileo Galilei’s 1610 illustrated book Sidereus Nuncius is the first scientific work to feature telescope-aided views of the skies. Its depictions of the moon’s craggy surface, the satellite moons around Jupiter and a multitude of previously unseen stars were more than fascinating. They provided empirical evidence of Galileo’s theory that the universe was heliocentric, rather than geocentric, helping to usher in a sea change in scientific thought. And when a copy surfaced in Italy a decade ago, a panel of experts made an exhaustive study before authenticating it.

The book sold for approximately $600,000 but was proved a forgery just a few years later. How had Marino Massimo De Caro, a high-profile curator, managed to fool the pros? It was the stuff of cerebral thrillers, and it was catnip to The New Yorker’s Nicholas Schmidle, who published an extensive interview with the master forger in 2013, one year after his arrest.

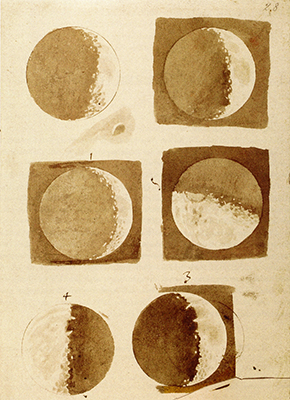

Galileo's lunar drawings, which gave his public a first close-up glimpse of the moon.

That article chronicled the end of De Caro’s career, but not the end of the story, says Professor of Art History Melinda Schlitt, who has studied the scholarly reverberations of this art-world scandal and the larger issues it raises. She will deliver a lecture on the topic on Thursday, Oct. 8 (Weiss Center, Room 235, 5:30 p.m.).

Modified from a keynote address Schlitt delivered last November during a conference at the Galileo Museum (Florence, Italy), the presentation outlines the historical role of imagery as part of scientific inquiry and delves into the ways that experts authenticate documents such as Sidereus Nunicus—issues stirred up in the wake of the forgery that rocked the art world.

Working in those contexts, Schlitt will shepherd the audience through a close examination of Gallileo’s lunar drawings, which have resided in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Fierenze since the early 19th century. Long deemed authentic, they are now the subject of intense scrutiny, as some ask whether they were made by one of Galileo's contemporaries, not the man himself.

“It’s important to revisit Galileo's moon drawings and the etchings in the 1610 Sidereus Nuncius within the cultural and artistic circumstances in which they were produced,” says Schlitt, William W. Edel Professor of Humanities, whose analysis shines interesting light on the intersections of linguistics, art and science. “Contrary to the recent assertion, the [forged and original Galileo works] only serve to validate the presence and veracity of Galileo's hand and mind as part of a longstanding tradition of Florentine draughtsmanship, wherein imagery could function as a form of empirical truth.”

Learn more

Published October 2, 2015