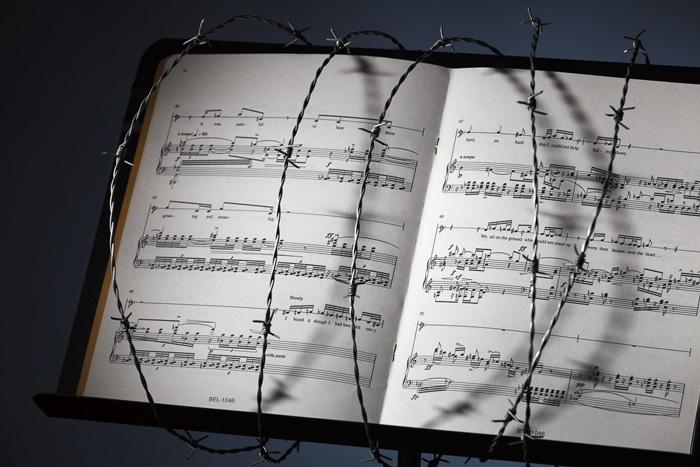

A Musical Witness

Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

Music professor breaks boundaries with analysis of Holocaust music

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

For decades, scholars have studied postwar Holocaust literature, visual art and film as expressions of hope and perseverance, as sociopolitical tools, as conduits of memory and as markers of history, trauma, Jewish identity and experience. But when it comes to Holocaust music, the scholars have been largely silent—until now.

A new book by Associate Professor of Music Amy Wlodarski is the first comprehensive analysis of secondary witness and representation in Holocaust music. Published by Cambridge University Press as a part of its Music Since 1900 series, Musical Witness and Holocaust Representation cements Wlodarski’s role as a leading voice in an emerging field.

Family ties

Wlodarski’s interest in the subject stems from her grandparents’ experiences during World War II. Her maternal grandfather was imprisoned by the Russians and later “liberated” to fight for the Polish resistance; her grandmother was shipped from her home in Poland to a forced-labor farm in southern Germany.

“If things had turned out differently, I probably would be teaching history now,” says Wlodarski, a former history major, “but I didn't want to turn my grandparents into a historical subject, and I didn't want to subject them to interviews, which they always resisted. They still live with that trauma.”

She instead began to explore the Holocaust through its music, and went on to study musicology at the graduate level, earning an M.A. and Ph.D. from the Eastman School of Music.

A burgeoning field

An award-winning educator who began her career at Dickinson in 2005, Wlodarski co-edited a 2011 book on East German art culture and published Musical Witness in August. In it, she defines the phenomenon of music-as-secondary -witness (the point of view of one who observes a historicized and aestheticized event, as opposed to experiencing it directly) and offers detailed cultural analyses of five musical works, providing a framework for a new subgenre that combines music, history, music criticism and cultural studies.

Wlodarski asserts that the composition of a Holocaust representation is a political act that reflects the composer’s understanding of, and relationship to, the Holocaust. By translating history into musical forms and idioms, she argues, composers engage with questions of trauma, history, identity and representation. They also wrestle with the slippery nature of memory and historical accuracy, which raises the question of whether secondary witness is beneficial or detrimental to our understanding of genocide. Musical Witness also contributes to the literature by taking these musical representations—many of which have been disregarded as melodramatic or kitschy—seriously.

“I started the project in 2003, and now it’s a burgeoning field of interest,” says Wlodarski. This fall, along with Professor of Music Jennifer Blyth, she will bring the subject to the Dickinson stage when she guides first-year students to make contextual videos about Jewish music for a live performance by Artists-in-Residence Adaskin String Trio. (A thematically similar November residency will bring a musicologist to campus to discuss music and the anti-apartheid movement.)

“It’s been rewarding to emerge as a scholarly voice within a field of scholars who are really pushing boundaries on how we think about the value of art and the power of the canon to both exalt and discriminate against certain composers,” Wlodarski adds.

Learn more

- “Wlodarski Named 2015 Ganoe Award-Winner”

- “Ethnomusicologist Receives Award”

- “10 Inspirations”

- “Student Video Goes Viral”

- Department of Music

- Latest News

Published August 24, 2015