Behind History Lies the Truth

by Tony Moore

"If you tell the truth, you don't have to remember anything." This is something Mark Twain quipped, but he probably wasn’t thinking about the different truths that can be told and how one truth can be swapped out for another, depending on who’s telling the story.

In Remembering the Atlantic Slave Trade, last fall’s Dickinson Mosaic, Assistant Professor of Africana Studies Lynn Johnson, Associate Professor of History Jeremy Ball and Joyce Bylander, vice president for student development, set out with eight students to explore how the slave trade is remembered and memorialized on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Atlantic slave trade occurred from the early 16th to the middle of the 19th century—lasting about 350 years. Over its course, it saw more than 12 million Africans forcibly extracted from the continent and shipped off across the world. Between 350,000 and 400,000 embarked on ships bound for what would become the United States—with between 10 and 20 percent dying during the voyages.

The 300,000 or so Africans who made it to our shores left behind a legacy and seeded a history that is still with us every day—sometimes in plain sight and sometimes not.

“We want to help students see that we can sometimes imbue sites with a story that we want to have told,” says Bylander, “but is it the truth, and what story is missing in whatever stories get told?”

Different versions of the truth

“The difference between this Mosaic and any other history course is that we didn’t really study what happened in the past,” says Frank Williams ’15, a law & policy and Africana studies double major. “We evaluated the present: How is the story of the slave trade being told right now—in Ghana, in South Carolina? What are the ways in which people in modern society are expected to understand the slave trade?”

Student coursework with all three professors focused on the significance of the “slave coast” of West Africa, representations of the slave trade and African survival through the lens of arrival in the New World.

But as with previous Mosaics—which have taken students from Morocco to Cuba to the Mediterranean—the answers to questions asked in the Atlantic Slave Trade Mosaic were found mostly outside the confines of history books. And for 16 days on two continents the group walked in the footsteps of the hundreds of thousands of slaves brought to the U.S.

“Having students be in Ghana and Charleston and giving them the tools to really think about, listen to and learn about these stories—that was really important,” Bylander says. “It was the ‘feeling,’ as one student put it. They needed to feel these places and not just read about them.”

And those feelings were at times overwhelming, as the Mosaic cast new light on “what could have been,” according to Dominique Brown ’15, a psychology and Africana studies major who traces her ancestry to Ghana.

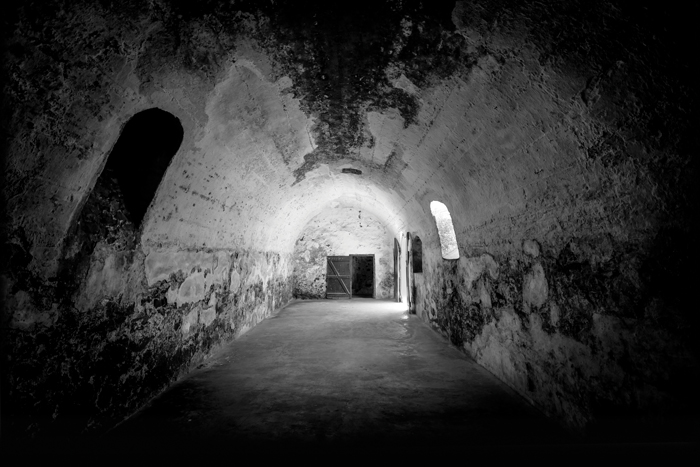

“Especially going through the dungeons, it’s hard to imagine that one of my ancestors could have been in conditions like this, and the only reason I’m here is because of that,” she says. “To think of that and to really experience it—it’s hard to explain, because there’s gratitude that’s associated with it, but there’s also sorrow.”

On either side of the ocean

In each Mosaic location—from Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle, Elmina Castle and Donko Nsuo (Slave River) at Assin Manso to Charleston’s Avery Research Center and Boone Hall Plantation—students were immersed in slave-trade narratives, and a striking trait of the experience was just how differently history was presented in West Africa and in Charleston.

“Everywhere in Charleston you walk around, you feel an ancestral presence, but no one is talking about enslaved Africans, even as you tour plantations,” Johnson says. “Just hearing the silence was profound to me.”

“It’s a silence that is stunning, and we continue to perpetuate it,” Bylander adds, elaborating on what is known as “heritage tourism.” “People like to go back to the past, but they don’t like to go back to the difficult past, and so if you don’t make the story nice, people won’t come to visit.”

“It’s a matter of whether you’re going to be an educator, or a learner, and go out and look for the true story,” says Hannah Glick ’15. “Because you could definitely go to these sites and see very elegant wallpaper, a nice piano, a nice portrait ... and miss the point of who was cooking the meals, who was taking care of the home, where the slaves were kept. To stray from this Gone With the Wind-style narrative is shocking, but it’s the truth.”

Conversely, in Ghana, Bylander says, “All they’re talking about is the enslavement of Africans, and they have been making that narrative prominent.” Johnson adds that it’s a narrative not just about loss but also about victory.

“The first time I went [to Ghana], I was in awe,” she says. “We survived this? They survived this? And then you start to understand that you need to learn more about it—not just about victimization but survival, and I wanted to make sure that was a narrative that the students understood.”

Legacies of the slave trade

With a new perspective of the past came a new understanding of the present, and the link between the two eventually led the group to look further at just what it means to call oneself “African American.”

“I always felt that I could not claim ‘African’ as a cultural identity because I was not born in an African country, and I don’t know where in Africa my ancestors came from,” Williams says. “I also felt like I didn’t fit the archetypal American figure. I was lost because I had no land to claim. But I realized that ‘African American’ is an identity in itself.”

That identity is something that has risen from the past, a past that many people would rather hide than explore. To Johnson, it is essential that the sights and sounds and experiences of the past be remembered, so they become the possession of the people instead of footnotes in history books.

“To be able to reclaim that history,” she says, “to be able to speak of it proudly and talk about the strength and survival of the people who made it, who made it possible for the rest of us to exist, was a really powerful and positive thing and something that the students embraced by the end of the Mosaic.”

Williams clearly found the Mosaic transformative, and he doesn’t shy away from any of the truths that revealed themselves over those weeks—truths that ended up spanning more than the Atlantic Ocean.

“I can’t control how my ancestors got to America,” he says. “But I can control the way in which I choose to carry out the legacies they created once they got here, and I embrace this wholeheartedly.”

Read more from the spring 2014 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Published April 22, 2014