Site of Memory

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

The Carlisle Indian School was founded in 1880 to "civilize" Native American children by teaching them to assimilate into European-American society. More than 130 years later, Native Americans from 25 states and more than 20 tribes will come to campus to reflect on the nearby school's shadowy past and its ramifications on contemporary life.

They'll come to attend the Carlisle Symposium, a two-day event sponsored by the Central Pennsylvania Consortium of Colleges, the Community Studies Center (CSC) and the School of American Studies at the University of East Anglia that brings together scholars, artists, writers, performers and activists from across the nation to share stories and explore issues facing indigenous peoples. Featured events include round-table discussions, walking tours, poetry readings, storytelling sessions, a photography exhibition and a plenary closing presentation by a Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

The historic location adds extra layers of meaning to each of these events, says Susan Rose, professor of sociology and director of the CSC. "Because of the Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle has always been a major site of memory [for indigenous peoples] all across the country," she explains. "It's as well-known to them as Wounded Knee, and for many, the associations are equally painful."

"Killing the Indian to save the man"

Located north of campus at the Carlisle Barracks, the Carlisle Indian School was founded in 1879 by Richard Pratt, an Army captain who had developed an English-language program for Native American prisoners in Florida some time before.

Pratt's premise was that cultural assimilation was a viable alternative to war, an idea that had been tentatively floated by George Washington a century before. He contended that instead of annihilating individuals in combat—a strategy that was costly, dangerous and, he felt, unenlightened—his school could simply annihilate Native American culture, one student at a time. Or, as Pratt described it, he would "kill the Indian and save the man."

"The sooner all tribal relations are broken up; the sooner the Indian loses all his Indian ways, even his language, the better it will be for him and the government," Pratt later declared in a memoir. Federal officials agreed and selected the Carlisle site—an abandoned cavalry post that was easily accessible by train. Pratt's first students arrived in October 1879.

Dubious success

The school would operate for 39 years, hosting a total of approximately 10,000 children from 140 tribes. Some of the students were willingly sent by families or tribal chiefs, who believed that the school offered the best opportunities for their children, since Native Americans were not then permitted to attend public schools. Others were kidnapped by school officials, eager to "Americanize" members of tribes that the government had deemed troublesome.

Of the few who graduated, many entered careers as teachers, tradesmen and athletes—the most notable being Carlisle's sole Olympian, Jim Thorpe, and Montreville Speed Yuda, father of the class of 1947's George Yuda. Many others, cut off from their native languages, identities and families of origin, entered a legacy of intergenerational trauma and disenfranchisement.

Still, Rose notes, in its heyday, the school was touted as a success, thanks to a crafty "before-and-after" marketing campaign. "Some of the students traveled for thousands of miles by train to get to the school, and [school representatives] would take their photos on their arrival, when they were tired and dirty," Rose explains. "For the second photo, they'd clean them up and cut their hair—a sign of mourning and emasculation for many indigenous groups. Then they'd dress them in military uniforms and shine a bright light on them, so their skin looked whiter."

Based on these perceived intercultural triumphs, the U.S. government would soon open approximately 100 additional Indian schools across the nation, both on and outside reservations (a handful of those original buildings today house reservation boarding schools). But for many, the institutionalized reprogramming of Native American youth remains synonymous with Pratt's flagship school in Carlisle.

Dickinsonian ties

Dickinson's CSC first shed light on this chapter in early American history by producing a student-faculty documentary by Rose and Manuel Saralegui '09 about two Lipan Apache children who were the sole survivors of a village massacre in 1877. Captured by the U.S. Cavalry on the Texas-Mexico border, the two siblings rode with the cavalry until 1880, when they were sent to the newly opened Carlisle Indian School.

The CSC had performed collaborative research on these "lost children" with Jacqueline Fear-Segal, a University of East Anglia (England) professor in American history and co-founder of the Native Studies Research Network (U.K.), and Carlisle Indian School researchers Barbara Landis and Geneive Bell. Fear-Segal, who would later pen a book on the subject, helped locate direct descendants of the two child survivors, and on May 18, 2009—the anniversary of the massacre of the children's village, known as the "Day of Screams"—those descendants came to Dickinson from Texas, New Mexico and California to perform blessing ceremonies.

The "lost children" descendants are among the more than 100 Native Americans who will attend the two-day Carlisle Symposim. Fear-Segal, who was a Dickinson fellow for two years while researching her book, also will fly in from England to present at the event.

Pushing buttons

While the stories, artworks, poems and remembrances shared during the conference represent personal experiences and culturally distinct tribes, they combine to create a compelling—and, often, chilling—narrative about the indigenous/settler experience and the ways it influences contemporary life.

The discomfiting nature of that narrative—and the discussion it sparks—is exactly the point.

"While this is an Indian problem, it is also a white person's problem. I like to say that it unsettles the settler within," Rose says. "So I'm sure that will stir strong emotions, and that's good.

"What we're doing is creating a chance to really listen and think through some very difficult issues together, as a community," she continues. "That's an incredible opportunity, an incredible experience."

Conference Highlights

Oct. 4 (pre-conference)

7:30 p.m.: Pre-conference roundtable on Indigenous Latin America

Oct. 5

9 a.m.: Opening Ceremony: Honoring the Elders

10:30-noon: Photography exhibitions of Carlisle and the Indian School

1:30: Storytelling: The Spirit Survives

6 p.m.: Lakota Dinner (pre-registration required)

7 p.m.: Poetry readings

Oct. 6

8 a.m.: Tour of Carlisle Indian School ($5)

9:30 a.m.: Panel discussions and presentations

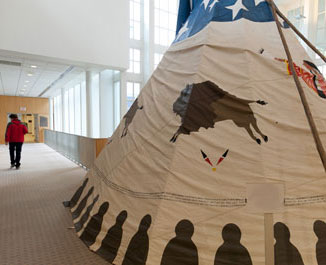

11:10 a.m.: Carolyn Rittenhouse: A Plains Indian Tipi Project

1:30 p.m.: "The Lost Ones: Long Journey Home" (film screening)

2:45: Genocide and Cameroonian women's history

4 p.m.: Plenary and closing with Pulitzer Prize-winning author N. Scott Momaday. This event will be streamed live on the Carlisle Symposium Web site.

View the complete schedule.

Find related Twitter posts: #CarlisleSymposium, @DsonCSC

Published October 3, 2012